It was

another chilly, but pleasant, sunny morning.

It was nineteen degrees at sunrise.

At 8 a.m., Brigham Young notified the camp to prepare to leave the Sugar

Creek Camp by noon. A meeting of the

brethren in the camp opened at 10 a.m. Brigham Young was not feeling well, so

he sent Heber C. Kimball to speak to them.

Elder Kimball expressed President Young's desire to move to a new

location. They were too close to Nauvoo

and many brethren continued to return to the city. They were neglecting their families and teams, worrying about

their property back in the city, and going to see their grandmother or

grandfather.

Elder Kimball continued

by prophesying that the Kingdom of God would be established. He encouraged the brethren to go forward,

that the grass would start growing soon.

“If Nauvoo has been the most holy place it will be the most wicked

place.” He called for all to do what

President Young asked. He warned them

about the plagues that fell on Zion's Camp.

At about 1 p.m., the

camp began to move and by 4 p.m., nearly 500 wagons were rolling forward,

traveling to the northwest for about five miles. It was a beautiful, warm day, and the wagons rolled through the

slush and mud. Many people came from

Nauvoo to say good-bye again to their family and friends. Some camp members stayed behind at the Sugar

Creek Camp because they were not ready or they were sick. For instance, Allen Stout stayed because he

had “sore eyes” and could not see. The

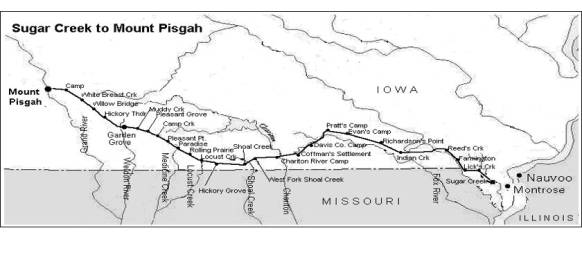

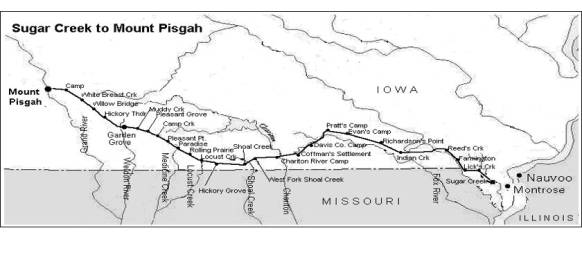

Camp of Israel traveled on the ridge in between Sugar Creek and the Des Moines

River.

Brigham Young's

carriage did not arrive from Nauvoo until about 4 p.m., which caused him to

delay his start. He arrived into the

new camp at sunset. The main camp was

situated on low ground among the trees.

As he was coming down a hill into the camp, President Young's carriage

almost tipped over. When Parley P.

Pratt was coming down another part of this hill, his “neck yoke” broke, causing

horses and wagons to plunge down the hill among the tents, women and

children. Thankfully, no one was

injured.

The men went to work,

set up camp, scraped away the three or four inches of snow on the ground, and

put up the tents. They built large

fires in front of the tents to keep their families warm.

The pioneers who had

preceded them to this camp a day earlier, had spent the day splitting 3,000

rails and husking 150 shocks of corn for local Iowan settlers in exchange for

corn and hay for the animals. Eliza R.

Snow, who came with this group the day before, watched the hundreds of wagons

come into the camp. As they rolled into

camp, she composed another poem:

Lo! a mighty num'rous

host of people

Tented on the western

shore

Of noble Mississippi

They for weeks were

crossing o'er.

At the last day's

dawn of winter,

Bound with frost

& wrapt in snow,

Hark! the sound is

onward, onward!

Camp of Israel! rise

& go.

All at once is life

in motion‑‑

Trunks and beds &

baggage fly;

Oxen yok'd &

horses harness'd‑‑

Tents roll'd up, are

passing by.

Soon the carriage

wheels are rolling‑‑

Onward to a woodland

dell,

Where at sunset all

are quarter'd‑‑

Camp of Israel! all is well.

Thickly round, the tents

are cluster'd

Neighb'ring smokes

together blend‑‑

Supper serv'd‑‑the

hymns are chanted‑‑

And the evening

pray'rs ascend.

Last of all the

guards are station'd‑‑

Heav'ns! must guards

be serving here?

Who would harm the

houseless exiles?

Camp of Israel! never

fear.

Where is freedom?

where is justice?

Both have from this

nation fled;

And the blood of

martyr'd prophets

Must be answer'd on

its head!

Therefore to your

tents, O Jacob!

Like our father

Abra'm dwell‑‑

God will execute his

purpose‑‑

Camp of Israel! All

is well.

After the tents were

pitched, Brigham Young invited the Saints to dance to the tunes of Captain

Pitt's brass band. About fifty couples

joined in the festive event. Some curious,

local Iowan settlers gathered around to watch and listen. The members of the band were most likely:

William Pitt, William Clayton, Stephen Hales, William Cahoon, Robert Burton,

James Smithies, Daniel Cahoon, Andrew Cahoon, Charles Hales, Martin Peck, J.T.

Hutchinson, James Standing, William Huntington, Charles Smith, Charles Robbins

and John Kay.

At 8 p.m., Parley P.

Pratt, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards met with Brigham Young in his

tent to make plans for the week. They

decided to move the camp again in the morning toward Farmington, where Bishop

Miller's group was working. Orson Pratt

met with two men from Iowa who were interested in buying his property in Nauvoo

for the low sum of about three hundred dollars. The sky was clear in the evening. At midnight the temperature was twenty‑eight degrees.

Several

miles ahead, a Brother Smith's child died.

Brother Smith was in George Miller's company of pioneers. Charles C. Rich helped bury the child and

he, along with Bishop Miller, preached the funeral sermon. A number of settlers in the area attended

and were attentive to the speakers.

John

Taylor's wife, Elizabeth, gave birth to a daughter, Josephine Taylor.

“Henry Bigler

Autobiography”, typescript, 17-18; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,” typescript, 47;

“Eliza Lyman Autobiography,” 8-9; Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R.

Snow, 115‑16; Leona Holbrook, BYU Studies, 16:1:125; Watson,

The Orson Pratt Journals; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 127‑29;

Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout; Watson, Manuscript History of

Brigham Young, 56‑8; Kimball, Heber C. Kimball ‑ Mormon

Patriarch and Pioneer, 130; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848

At 7 a.m.,

the temperature was twenty-three degrees.

At 9 a.m. the teams started moving out of the camp. There was some confusion because some of the

companies had camped down in the valley

while the other part was up on the prairie.

The groups left their camp on different roads. Brigham Young took the lower group across Sugar Creek and Hosea

Stout took a group of 200 wagons on the ridges.

The camp traveled

about ten miles over “several tedious hills” through mud and water. Hosea Stout recorded:

We had a very bad road

all day and often at hills and difficult places to cross branches [of

streams]. I saw teams standing waiting

for those forward to pass over which were a mile long and often at hills teams

would stall and have to be rolled up by hand thus making it both laborious for

men who were on foot, and also slow for the teams to be thus detained for each

other. It was beautiful country.

At some point during

the day, the companies reached a summit of a hill where they were able to catch

a glimpse of the Nauvoo temple, far to east.

Lewis Barney wrote:

On reaching the summit

between the Mississippi and Des Moines Rivers the company made a halt for the

purpose of taking a last and peering look at the Nauvoo Temple, the spire of

which was then glittering in the bright shining sun. The last view of the

temple was witnessed in the midst of sighs and lamentations, all faces in gloom

and sorrow bathed in tears, at being forced from our homes and Temple that had

cost so much toil and suffering to complete its erection.

At 2 p.m., Hosea

Stout went ahead on horseback to try to find the “forward team.” He was concerned that he may have had the whole

wagon train heading down the wrong road, which would have been a disaster and a

great loss of time. He found a house,

asked directions, and found out they were heading the right way. He soon located the “forward team” of

Stephen Markham, Brothers Darby and Allen who were trying to purchase corn and

hay for the camp that night. A field

was located nearby which was a beautiful piece of ground in timbered land. There was timber already cut and scattered

in piles almost as if they were prepared for the camp. The owner let the camp use the wood for

fires. The wagons arrived and formed

the camp which was on the west side of Lick Creek1

about a half mile from its junction with the Des Moines. The waters of the rivers were very

clear. “The country was timber land and

quite broken, with high bluffs rising loftily over low valleys, and but little

cultivated.” The people who lived

nearby were friendly and gave members of the camp straw for their cattle.

At some point during

the day, there was a problem with teams using two converging roads. This caused some separation of teams and

collisions, resulting in damage to some wagons. The artillery company broke several of the William Clayton

company wagon boxes.

Heber C. Kimball and

Newel K. Whitney had to stay behind in the morning to mend a wagon. This delay caused them to end up camping

three miles behind the main camp.

Samuel Bent and a few others stayed behind to finish up the work that

they were hired to do.

Orson Pratt traveled

on horseback to Farmington, where he looked at the items which were being

offered in exchange for his Nauvoo property.

He did not reach a firm agreement with the men. He headed back to meet the camp, but they

did not take the route across the prairie which he had expected them to

take. After some time searching, he

finally found the camp. Each night

Elder Pratt would calculate the latitude of the camp by using the stars. The band played in the evening.

Warren

Foote was mourning the continued sickness of his mother who had been recently

baptized. He wrote:

I felt very much cast

down in my mind. I felt that I had done

all I could for her in my circumstances, and still I had a desire to know if

there was anything more that I could do.

I was impressed to go and pour forth my soul to my Father in Heaven in

secret. I did so, and through the

inspiration of His Holy Spirit it was made known to me, that I had done all

that was required of me for her; and that she would be taken from me, and that

she should rest with Father, and should come forth with him in the morning of

the first resurrection, and receive an exaltation with him in the Celestial

Kingdom of our God. Therefore though I

mourn my bereavement of her for a season, yet I rejoice in the promises of the

Lord.

Thomas

Bullock was out of employment. He had

been working for Willard Richards in the Historian's Office, but Elder Richards

was no longer in Nauvoo. Brother

Bullock went to the temple office and showed them orders from Elder Richards to

take Thomas Bullock into their temple office.

Almon W. Babbitt refused to hire him, saying that he only took orders

from Brigham Young. Brother Bullock

went away feeling hurt and disappointed.

A daughter, Isabella

Jane Forsyth, was born to Thomas and Isabella Forsyth.2

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 59‑60; Stanley Kimball, “The Iowa Trek of

1846"; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout; The Orson Pratt

Journals; William Clayton’s Journal; “Warren Foote Autobiography,”

typescript, 76; Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 116;

“Thomas Bullock Journal,” 55; Black, Membership

of the Church 1830‑1848; “William Huntington autobiography,”

typescript, 48; “Lewis Barney Autobiography,” typescript, 28

At 7 a.m.,

the temperature was twenty‑three degrees. The weather was very pleasant and warm all day. At about 9 a.m., the bugle was sounded

calling the camp together. Brigham

Young gave them some instructions. He

told the “pioneers” to go ahead and prepare the roads by cutting and trimming

trees and filling up the bad places in the roads. He instructed the guard to carry axes instead of guns, and to

help the teams. They should not order

the teamsters. Everyone should help

each other. He asked any man to quit

the camp who could not quit swearing.

President Young wanted to correct the traffic problems that were

encountered the previous day. He

instructed the men that the teams must not crowd each other. The ox teams must let the faster horse teams

pass. No teams should come within two

or more rods of each others. President

Young directed those designated as “pioneers” to leave first, followed by the

band, then the ox teams, and the remainder of the camp.

The camp soon started

to move up the north bank of the Des Moines River. Hosea Stout observed that the Des Moines was “a beautiful stream

with a rock bed but appeared very narrow after being so long accustomed to the

broad rolling Mississippi.” The road

was dry and level.

At 10:30 a.m.,

Brigham Young left the Lick Creek Camp along the same route and arrived in

Farmington at noon. He traded in the

town for thirty minutes. Hosea Stout

also went into town. “It is situated on

the river, the site is level and not very romantic but rather dull looking and

I should think sickly.” When Brother

Stout went into the store, there was a group of shady looking characters who

looked like they wanted to start a fight, but Brother Stout kept his two six‑shooters

and a large Bowie knife in plain sight, and they stepped aside when he came

near them.

The rest of the wagon

train soon passed through Farmington.

While traveling through town, one of Brother Roger's boys drove his team

accidentally over a hog and killed it.

The owner witnessed the event, did not seem to mind, and retrieved the

carcass. However, some of the rough

characters in town came forward, swearing, and demanded that the owner be paid

for the hog. Some of the brethren

agreed while others did not. Brother

Hunter, of the guard, came forward, ordered the teams to move on and decided

that payment did not need to be made for the hog. The Farmington men made remarks about Brother Hunter’s guns. Brother Hunter let them know that the guns

could be used if he was molested. Eliza

R. Snow wrote that the people of Farmington “manifested great curiosity and

more levity than sympathy for our houseless situation.”

From Farmington, the

wagon train continued up the north bank about three miles, where they reached

the next encampment. The roads for

these final three miles were bad and several wagons were broken and

damaged. The camp was about three

quarters of a mile north of the Des Moines River, on a ten-acre lot owned by

Dr. Jewett. This land had been cleared

of timber and fenced by George Miller, Charles C. Rich, and about thirty or

forty pioneers who had been there for about a week. The camp was situated on the bank of a small, clear creek. Because of the warm weather, the ground was

thawed, and was quite muddy, making it unpleasant for those who would need to

sleep on the ground. Orson Pratt

scraped together some leaves which helped to keep his family out of the

mud. Most of the camp arrived before dark. They had traveled about eight miles.

Hosea Stout arrived

at 2 p.m. and chose a nice spot for the guard to camp. But he soon found out that the place he

chose would be occupied by President Young and others. Brother Stout believed that he should step

aside for his priesthood leader, so he selected a nice new spot in a wooded

area with sugar maple trees. He was

then informed that the owner of the land did not want anyone camping in the

woods. Brother Stout decided that they

would go ahead and work things out with the owner if needed, because all the

best ground within the field was already taken. After they had set up camp, the owner came and was satisfied with

what he saw. He just asked them not to

use any green wood or wood that could be made into saw logs.

The evening sky was

clear and beautiful. The band played in

camp. As Eliza R. Snow was eating her

supper while seated in her buggy, she was surprised to see Sister Elizabeth Ann

Whitney who came to visit. Sister Snow

was delighted to hear that the Whitneys had arrived into camp and were tented

nearby.

George Miller brought

Dr. Jewett to meet Brigham Young. Dr.

Jewett related a long history of experimentation with “animal magnetism”

(hypnotism), claiming that it had nearly cured him of infidelity. Dr. Jewett asked what the Mormons thought of

the principle. Brigham Young made it

clear that they believed in the “Lord's magnetism.” The Lord had “magnetized” Daniel so that he could interpret the

hand writing on the wall.3

Corn was brought into

the camp, including one hundred and seventy-two bushels of tithing corn, and

corn received for payment for the work completed by George Miller and the other

pioneers.

Former

apostle, now Strangite, John E. Page preached in the temple on the west stand

at 1 p.m. He spoke against the Twelve

and claimed that James J. Strang was the true successor of Joseph Smith. Jehiel Savage also spoke in support of

Strang. Elder Orson Hyde then spoke,

and according to Thomas Bullock, “knocked every one of their arguments in the

head and ordered Savage to go to Voree [Wisconsin] and tell them [followers of

Strang] they would be damned. . . .”

Elder Pratt also spoke words of reprovement toward Page. Page was then said to have stated “I will go

to hell sooner than take abuse, and the Devil shall have it to say 'here is a

man that is damned like a man.'” The meeting closed at 4:30 p.m.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 61‑63; Stanley Kimball, “The Iowa Trek of

1846";Watson, The Orson Pratt Journals; Brooks, The Diary of

Hosea Stout; William Clayton’s Journal; Beecher, The Personal

Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 116‑17; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” 56

The

morning was warm and the day was beautiful.

The camp was awakened to the music of the Band which was “delightfully

sublime.” At 8:00 a.m., the temperature

was forty‑three degrees.

At 9 a.m., Brigham

Young called the brethren in the camp together and announced that they would

remain in the camp until the following day, when part of the camp would move

out. He wanted everyone to be busy

during the day repairing and greasing their wagons, shoeing their horses,

mending harnesses, getting ready for an early start the following day. Each team would be provided with two days of

corn.

At 10:30 a.m.,

Brigham Young met with members of the Twelve, the bishops, and a few of the

captains. It was agreed that a few of

the pioneers and George Miller would go on twelve miles, right away, to form

another camp. The remainder of the camp

would be numbered again and be divided into hundreds and fifties under the

direction of the Twelve. The first

hundred would start in the morning.

Two tons of hay was

purchased and brought into camp. George

Miller rolled on ahead with some pioneers, heading in a westerly direction,

crossing the Des Moines River at Bonaparte Mills.

At 12 p.m., Hosea Stout

called a meeting to discuss the need to have the guard work together and spoke

to them at length about the guard working their way to relieve the Church from

the expense of supporting them. They

should work when the camp was not traveling.

After the meeting, Charles Allen, a captain in the guard, held a meeting

with his men and declared that he would not work, would not take orders from

Hosea Stout, but that he would go by himself to President Young to receive

orders. Some joined in with him in these

feelings.

Brother Scott found

some work for the camp involving removing dirt from a coal bed, and splitting

two thousand rails. The payment for the

work would be in flour, pork and cash.

Fifty men started to work on the contract.

Many citizens of the surrounding

area walked into the camp, strolling down the makeshift streets of the

temporary city. Orson Pratt finished the negotiations with men in Farmington

who wanted to buy his Nauvoo property.

Some of the citizens

from Farmington came into camp and invited the band to go to their village for

a concert. The band left at about 3

p.m. on horseback, arriving in Farmington at about 4:30 p.m. They played at the hotel, then went to the

schoolhouse and played until dark. The

house was filled with men and women, including the town leaders. The band was fed supper in the hotel and

given five dollars. At 8 p.m., they

left the town and were given three cheers.

On the way, they were met by thirty of the guard, who had just started

out to find them. President Young had

felt uneasy about them returning without men to protect them. They returned to camp at 9 p.m.

In the evening, Eliza

R. Snow took a walk with Hannah Markham and they lost their way in the large

tent city. They stopped at Elder Amasa

Lyman's tent and after chatting with Eliza Partridge Lyman, Elder Lyman

escorted the ladies toward their camp.

The buggy which Sister Snow had been using as her sitting room and

dormitory was exchanged this day for a lumber wagon by Brother Markham.

Also in the evening,

Brother Stout reorganized the guard.

Because there were no longer enough men for four groups of fifty, he

wanted to reorganize with three groups of fifty. The reorganization was performed and supported by the guard. Right after this, Brother Stout was called

to go camp headquarters, instructed to divide the guard into four groups, and

to have one group ready to leave in the morning. Brother Stout went back to the guard and let them know that the

reorganization performed earlier was void.

John D.

Lee left Nauvoo, and started his return trip to the Camp of Israel. He had returned to the city to help free

some relatives who had been arrested.

With everything settled, he started his return journey. George Laub crossed the Mississippi River on

a flat boat with Brother Lee's teams and goods. The river was no longer frozen and crossings were again made by

boat. The Lee family camped for the

night about one mile from the Mississippi River.

The ship Brooklyn

crossed the equator about this time, heading south for Cape Horn. Samuel Brannan organized the ship into a

form of the United Order. They would be

in one body and share together the debts of the voyage. They were asked to agree to give three

years’ labor into a common fund. If

they left the covenant, the common property would remain with the elders. It was an imperfect agreement, and there was

some grumbling, but they all signed their names to the agreement.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 63‑64; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout;

Watson The Orson Pratt Journals; William Clayton’s Journal;

Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 117; “George Laub

Autobiography,” typescript, 38-39; Bailey, Sam Brannan and the California

Mormons

At 8:30

a.m., Brigham Young held a meeting with the brethren in the camp. He asked for three teams to pull the cannon

and called for volunteers to husk corn at the next camp. He announced that only the first company was

leaving on this day to prepare the next camp.

If there was a family without the means to continue, they must be

provided for. No one was to be left

behind who wished to continue. He

recommended that they should lighten their loads by eating certain food that

could be replaced. When they reached

the Missouri river, they would go to work and buy more flour and other

foods. After the meeting, several men

came forward and offered to pull the cannon.

A Colonel Swazy and his

family visited the camp and mentioned that the band's performance last evening

had created many good feelings among the citizens of Farmington.

At 10 a.m., Brigham

Young rolled out of the camp with the

first company. They traveled along the

banks of the Des Moines River for two miles and crossed just below Bonaparte

Mills. The water was about two feet

deep with a nice rocky bottom. Sister

Eliza Snow wrote about their day’s journey:

Sis[ter] M[arkham] and

I are nicely seated in an ox wagon, on a chest with a brass kettle and a soap

box for our foot stools, thankful that we are as well off. The day fine, we travelled 2 miles on the

bank of the river & cross’d at a little place called Bonaparte. I slung a tin cup on a string and drew some

water which was a very refreshing draught.

The company proceeded

up the west bank of the river for a short distance and passed through the

little town of Bonaparte. There was a

“splendid” mill on the river in this town.

A dam at the mill extended across the entire river and a lock was used

to pass boats up or down the river.

After Hosea Stout

passed through the town, he found the road full of wagons and teams standing

still. He knew that something was wrong

and went on ahead to check things out.

Not far up the river, the road took a branch and then went up a

hill. The teams at the bottom of the

hill were waiting because the hill was full of stalled wagons stuck in the

mud. On the sides of the road there

were thick woods which prevented the teams from going around bad spots. The wagons would frequently sink all the way

down to their axles. This two-mile

stretch was by far the worst road that the camp had experienced so far.4

Eliza Lyman called it “the most muddy road I ever saw.” As Father John Smith’s wagon was traveling

up this steep road, it tipped over injuring Sister Smith slightly.

Brigham Young arrived

at the top, on the prairie at about 1 p.m.

A load of corn was supposed to be there, as planned the day before. He

was disappointed to find nothing left there by the advance group. The horses had not been fed in the morning,

so they were turned loose on the prairie to eat the scarce dry grass. Men were sent back one mile to purchase a

load of corn. Hosea Stout found corn at

the home of an uncle of Charles C. Rich.

By 4 p.m., most of

the teams in the first company had come up to the prairie and the horses had

been fed. The camp traveled west on a

very good road for seven miles and started to make camp at about sunset on a

low piece of flat prairie land on the north bank of Indian Creek.5

The camp had traveled twelve miles on this day.

Brigham Young had

expected to see George Miller and his pioneers to help provide feed for their

exhausted teams. But there was no sign

of this company. Corn had to be

purchased with cash, enough to give each beast eight ears.

The ground was too

wet to pitch tents, so most of the camp stayed in their wagons. Despite the uncomfortable conditions, there was

no murmuring and all appeared to be happy.

Several horses were sick. One

thought to have distemper was removed from the camp. When Brigham Young arrived, he did not like the location that had

been chosen for him. He pitched his

tent on the bank of Indian Creek in the woods at about 10 p.m.

It was learned that

Newel K. Whitney broke an axle and was camping on the south bank of the Des

Moines River. Elders Heber C. Kimball,

Parley P. Pratt, John Taylor and John Smith were camping out on the prairie between

four and seven miles to the east. Their

teams could not travel further that day, after coming up the long, muddy

hill. This group did not have a fire

that night and had to have a cold supper.

Some neighbors gave them some straw for the animals. Orson Pratt learned that a wagon that was

carrying one of his loads broke an axle further back.

Late into the night,

George Miller and Henry G. Sherwood called on Brigham Young and told him their

company did not stop at this spot as planned because they could not find

work. They had continued on fourteen

miles further and found a place to camp near Brother Stewart's home. George Miller's company had been busy that

evening harvesting Brother Stewart's corn to help pay his debts and to bring

the rest of the corn to the camp.

The snow

was nearly all melted and the river almost open, free of ice. Warren Foote’s mother, Irene Lane Foote

died, at about 4 a.m. She had joined

the church on February 28. Brother

Foote mourned for his mother:

My feelings at this

moment who can describe. O how much

care she has taken of me, how many sleepless nights she has spent watching over

me through the many spells of severe sickness I have had, when nothing but a mother's

care could have saved my life, with the blessings of God. O how little I have repaid her for all this

care and anxiety, but if the Lord will spare my life, I will see that her work

in this probation is completed and united with Father through the sealing

power, no more to be parted forever.

A daughter, Melissa

Miner, was born to Albert and Tamma Durfee Miner.6

Elder

Addison Pratt experienced the great missionary joy of receiving a letter. He wrote: “This is a day long to be

remembered. We have received a letter

from Br. Woodruff dated November 1844.

This is the first letter from the Twelve. . . . Tho old as this letter

is, it contains news that is as refreshing to us as cooling waters to a thirsty

soul.”

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 64‑66; Stanley Kimball, “The Iowa Trek of

1846"; Watson, The Orson Pratt Journals; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea

Stout; Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 117‑18;

“Thomas Bullock Journal,” 57; Kimball, Heber C. Kimball ‑ Mormon

Patriarch and Pioneer, 132; “Warren Foote Autobiography,” typescript,

76-77; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848; “William

Huntington autobiography,” typescript, 48; Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:323;

Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman, Pioneer, 148; Ellsworth, The Journals of

Addison Pratt, 273

At 7 a.m.,

the temperature was thirty‑five degrees.

The weather was clear, pleasant and warm. One of Brigham Young's horses died during the morning. It turned out that the other horse suspected

of having distemper, did not have it after all and was returned to camp. In the morning, many of the Saints decided

to move their tents and wagons to the banks of the creek, where it was not

quite as muddy.

Parley P. Pratt and

his company arrived at the camp at 11 a.m.

But they continued to travel on to the west, to start working on a local

contract to split rails and clear land.

Heber C. Kimball arrived at 1 p.m. and John Taylor arrived at 2

p.m. One hundred bushels of corn were

purchased for the camp.

Hosea Stout had to

deal with more dissension among the guard.

Samuel Gully, one of the captains of the guard, had brought his wagon to

the Reed's Creek camp. There, he met up

with his wife, and declared that he would have nothing more to do with the

guard and advised his men to join other companies. He complained that he was not used well, but had never mentioned

anything to Brother Stout. He took his

yoke of oxen, and took his things out of the wagon that he left by the

roadside.7 When Brother Stout heard about the

problem, he sent two members of the guard with three yoke of oxen to bring up

the wagon. They started heading back at

4 p.m. and returned with the wagon before daybreak, traveling all night.

In the evening,

Charles Allen continued to disregard Hosea Stout's orders. Brother Allen's group of guards was called

to take their regular turn guarding the camp, but he refused to let anyone go,

saying that they were too tired.

In the evening, Dr. John

D. Elbert, a nearby resident, came into camp and met with Brigham Young and

Willard Richards in Elder Richards’ tent.

Dr. Elbert stated that when news first arrived that the Mormons were

coming, there was much excitement and worry because of the false reports that

had been circulating. They feared that

“they should be swallowed up alive” by the Mormons. But the more recent reports of honest dealings with the camp had

helped to calm the fears. Dr. Elbert

said that he had treated several Mormon families who lived in the vicinity and

that all had paid him honestly. He couldn't say the same for all the non‑Mormon

families. Dr. Elbert set aside a

section of land seven miles ahead for a camp and contracted with the brethren

to split rails and clear land. Payment

would be in corn. While the Doctor was

there, the band came up to the front of the tent and played for him.

Brigham Young wrote a

letter (penned by Willard Richards) to Orson Hyde in Nauvoo, reporting that all

was well and that the camp was in good spirits.

Christina,

wife of John Lytle, delivered a son, Charles Lytle, at 2 p.m.8

The ice

was finally broken up and was running on the river. Brother Charles W. Wandell wrote a bogus revelation to see what

effects it would have on the Strangites.

He sent it to Jehiel Savage, a Strangite, telling him it was a

revelation from the Lord given through James J. Strang. Savage took the revelation and from the

temple stand read it to the people, bearing testimony that he knew it was from

the Lord. Brother Wandell came forward

and acknowledged that he was the author of the article, that the Lord had

nothing to do with it, and that Strang never saw it. Brother Wandell later found out it was unprofitable and dangerous

to use the name of the Lord falsely, that it produced evil among men. While it did show the brethren that the

followers of Strang were more ready to receive fables than truth, the brethren

understood that no man should use this deceptive method.

A daughter, Louisa

Cox, was born to Amos and Philena Cox.

A son, Henry Jefferson Keele was born to Richard and Nancy Keele.9

Lydia Faunce was also born in Nauvoo on this day.

Wilford

Woodruff arrived on a ship from Liverpool, England.

Cowley, The

Discourses of Wilford Woodruff, p. vii; Watson, Manuscript History of

Brigham Young, 66‑68; Comprehensive History of the Church,

3:112; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout; Watson, The Orson Pratt

Journals; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848; “Thomas

Bullock Journal,” 57

At 7 a.m.,

the temperature was thirty‑two degrees.

The skies were clear and the day was pleasant. The wagons moved out of camp in the morning.

After traveling about

two and a half miles on bad roads, Brigham Young stopped in the morning to

transfer a load of biscuit from some sacks to boxes. The sacks were worn through by the traveling. While he was working, most of the wagons

passed him. When he was finished, he

caught up and overtook many of the teams after another four miles. The roads during this stretch were much

better. Eliza R. Snow got out of her

wagon and walked for the first time on the journey. The timber in this area was mostly oak which was quite different

from the maples that they had become accustomed to near the Des Moines River.

Brigham Young reached

Dr. Elbert's campground where part of the group was already setting up

camp. Hosea Stout had arrived at 1 p.m.,

after a two-hour journey, and had pitched his tent on a beautiful ridge.

Word came to Brigham

Young that there were better locations for camping further ahead. Because the traveling was so nice, and the

day was pleasant, President Young decided to go on another five miles to a

place called Richardson's Point. The

roads were bad along this next stretch.

They then passed through several miles of rolling prairie and they pitched

their tents at about 4 p.m., on a very dry spot, close to the road, and near a

branch of Chequest Creek.10 There was plenty of corn nearby that could

be obtained in exchange for splitting rails.

The Camp of Israel was fifty‑five miles from Nauvoo. Some of the wagons arrived after dark, but

traveling at night was possible because the moon shined very bright.

There was confusion

at the Dr. Elbert camp because Brigham Young did not stop as planned. Some of the guard took down their tents and

followed after him. Hosea Stout did

likewise and arrived at Richardson's Point at dark. Hosea Stout sold a bedstead for eight bushels of corn that he

used to feed the guard's animals. His

wife had been afflicted with much pain in her right side and was unable to sit

up in the wagon all day. They had made

a bed for her to lie in, but even with extra care, the traveling during the day

was painful for her.

Newel K. Whitney

camped about two miles back. Amasa

Lyman, the band, and a portion of the guard camped at Dr. Elbert's camp, four

miles back. The band worked on splitting

130 rails for Dr. Elbert. In the

evening Dr. Elbert and some others came to hear the band play. John Kay also sang some songs which pleased

the visitors.11

Parley P.

Pratt and Orson Pratt continued on four more miles to George Miller's camp on

the Fox River. In this region was

located a small branch of the Church.

They camped near Brother Stewart's home. Some corn was donated to the camp, which was gathered by George

Miller and his men.

The ice

was running on the river and three steam boats were spotted across from Nauvoo,

puffing upstream. Pigeons were seen

flying north in large numbers. There

were some false rumors circulating through Nauvoo. The first rumor was that John Taylor was on his way to Nauvoo to

preach his last Mormon sermon. The

second rumor was that Hosea Stout had shot President Brigham Young, and Brother

Stout had been hung by the neck on a tree.

It was said many of the guard had left the camp. These rumors were of course false.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 66‑68; Stanley Kimball, “The Iowa Trek of

1846"; Watson, The Orson Pratt Journals; Brooks, The Diary of

Hosea Stout; William Clayton’s Journal; Beecher, The Personal

Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 118; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” 57; Black, Membership

of the Church 1830‑1848; Holzapfel, Women of Nauvoo, 142; Woman’s

Exponent 12:9-12

The

weather was dry, warm, and pleasant. At

6:52 a.m. a son, David Kimball Smith, was born to Heber C. and Sarah

Kimball. This birth occurred where

Bishop Whitney was camping, two miles east of Richardson Point. He was given the last name of Smith, no

doubt in honor to Joseph Smith whom Sarah was sealed to. Sarah was the daughter of Bishop Newel K.

Whitney.12 Using Book of Mormon tradition, Elder Kimball named the valley

his son was born, the Valley of David.

At 11 a.m., a Sabbath

meeting was held, attended by many in the camp and about forty or fifty

nonmembers from the surrounding area.

Elder Jedediah M. Grant spoke on the first principles of the

gospel. He was followed by Elder George

A. Smith. Eliza R. Snow went to the

meeting, but when she discovered that the talks were addressed mainly to the

nonmembers present, she decided to go visit Sister Leonora Taylor, wife of

Elder John Taylor. Sister Taylor was

feeling down because she was experiencing great pain caused by rheumatism. Sister Snow spent three hours encouraging

her, and letting her know that God would heal her.

Brigham Young and

Heber C. Kimball rode three to four miles west to inspect the campground that

was previously selected by George

Miller on the west bank of the Fox River.

It was located near Brother Stewart's home but they found the ground was

too wet there. They decided to keep the

camp where it was, at Richardson's Point, until Tuesday. Brigham Young had heard that George Miller

had obtained and stored one hundred and seventy-five bushels of corn for the

camp. When President Young came to the

camp at Fox River, he was disappointed to learn that George Miller, Parley P.

Pratt and others had gone on ahead that morning and taken the corn with

them. Several companies, not

understanding the new plans, had started to head for the Fox River camp. These groups turned around and went back

when they learned about the new plans.

The William Pitt

band, at Dr. Elbert's Camp, four or five miles behind the main camp, spent the

morning playing for many of the residents who lived nearby. They greatly enjoyed hearing the band and

gave them an invitation to play in the town of Keosauqua. The invitation could not be accepted right

away because instructions had been

given for the band to join the camp at Richardson Point. The band immediately took down their tents

and arrived at the main camp at about 5 p.m.

Some of the citizens of Keosauqua followed the band to the camp, hoping

that permission would be granted to accept their invitation. President Young advised the band to accept

the invitation and arrangements were made for a concert on the following day.

Other groups rolled

into the Richardson Point Camp. Brigham

Young's brother Lorenzo was among those who arrived this day.

Brigham Young and

Heber C. Kimball rode two miles back, to the Valley of David, probably to be

with Sarah Ann Kimball and the new baby.

They returned to the main camp at Richardson Point at 9:30 p.m., at

which time a council meeting was held for the first time in Brigham Young's new

large tent. The discussions centered on

a travel schedule needed for an advance party to reach the Great Basin region

soon enough in the season to plant a crop.

The proposed plan was to have a body of about three hundred men leave

their families and travel with speed over the mountains.

The Council discussed

the need to have John L. Butler return to the Emmett company.13

It was time to have this group of Saints gathered in with the main body

of the Saints. The Council also

discussed retrieving George Herring, an Indian, who was two hundred miles to

the south, preaching the gospel to his tribe.

(See October 29‑30, 1845.)

The Council meeting lasted until midnight.

A meeting

was held in the temple. Elder Orson

Hyde read a letter that he had received from Brigham Young (see March 6,

1846) stating all was well in the camp.

This put to rest the crazy rumors which had been circulating the day

before about Hosea Stout killing Brigham Young.

After preaching,

Elder Hyde’s brother‑in‑law, Luke S. Johnson,14

arose and addressed the congregation. He told how he had for some time been away from the work of the

Lord, but his heart was now with the Saints, and he wanted to go west with

them. A vote was taken whether to accept

him back. Brother Johnson was so

affected by the outpouring of support that he wept with joy, as did many

others. At 5 p.m., he was re‑baptized

by Orson Hyde in the Mississippi River.

Three other people were also baptized.

At 7 p.m., Elder Orson Hyde

confirmed Luke S. Johnson a member of the Church in the temple attic.15

At 2 p.m., William

Smith (brother of Joseph), former apostle, not a member of the Church, arrived

in Nauvoo by boat with a group of drunken men who started to fire their guns

into the air, creating a great disturbance.

William was not welcomed warmly back to Nauvoo this day because he had

been publicly preaching against the Church and its leaders. (See October 21

and 28, 1845.)

In the afternoon,

John E. Page preached a sermon in support of Strangism in the streets of

Nauvoo. A hat was passed around for a

collection. It was returned with a few

pennies, chips, buttons, and sticks, indicating that his words were not being

accepted by the faithful members of the Church.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 71‑72; Kimball Heber C. Kimball ‑

Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer, 133; Hartley, My Best for the Kingdom,

187; “Hosea Stout Diary”; Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:709

JOHNSON, Luke S.; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout; William Clayton’s

Journal; Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 118;

“Thomas Bullock Journal,” 57; Bruce Van Orden, Church News, March 8,

1996; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848;

The weather was very

pleasant, thirty‑two degrees at sunrise.

The morning sky was clear and bright.

At 10 a.m., the Twelve met in council in Brigham Young's large field

tent. They wrote a letter to the Nauvoo

Trustees. Instructions were given to

gather up cows, sheep, oxen, mules, pigs and other animals to be taken with the

next group of Saints who would leave Nauvoo.

Elder Orson Hyde was instructed to remain in Nauvoo to dedicate the

temple if the Twelve were not able to return to for this event.

The Council

instructed Captain John Scott, in charge of the artillery, to bury between

twenty-three and twenty-four hundred pounds of cannon balls, near Richardson's

Point Camp, to lighten the loads. The

cannon balls would be retrieved at a later time. The Council again attempted to better organize the camp. They decided to form new companies of

“fifties.” These groups of fifty wagons would be led by Brigham Young, Parley

P. Pratt, Amasa Lyman, and George A. Smith.

These independent companies would leave the camp at different times.

Hosea Stout was asked

to determine how many of the guard could continue on over the mountains,

without returning to Nauvoo to bring their family and other belongings. Brigham Young was being constantly

approached by many men who desired to be allowed to return to Nauvoo.

Brother Stout

continued to try to provide for the men under his charge. On this day he sold his table for a hog

which was divided among the guard, making up about one meal.

Many companies

arrived at Richardson's Point. Eliza R.

Snow wrote: “Our town of yesterday

morning has grown to a City.” Newel K.

Whitney arrived at about 3 p.m., moving his company from their camp two miles

away. Alexander Merrill came into the

camp bringing news from Nauvoo that William Smith (the Prophet Joseph's

brother) had returned to Nauvoo. Samuel

Bent, Charles C. Rich, Peter Haws, Shadrach Roundy and others joined the camp,

coming in from the Reed’s Creek Camp, below Bonaparte.

The camp was very

busy during the day. A blacksmith's

shop was observed in full operation.

The sisters were busy cooking.

Hannah Markham baked eleven loaves of bread. Washing clothes was not as convenient as in former camps because

the water was not located as close.

Tubs and washboards were taken about a half mile to the side of a

stream. Meals consisted of pot‑pies

of rabbits, squirrels, pheasants, quails, prairie chicken, and other items that

the hunters would catch.

In the evening, rain

started to fall. President Young and

Elder Willard Richards visited with Edwin Little, Brigham Young's nephew, who

was very sick in his tent. They

counseled him to leave the camp and to stay with his brother who lived in the

area.16

At 8 p.m., Henry G.

Sherwood came into camp. He had been

with the advance group of George Miller and Parley P. Pratt. Brother Sherwood reported that a fine

location for a camp had been located near Bloomington.

Brigham Young

finished writing to his brother Joseph Young, who had been appointed to preside

over the Church remaining at Nauvoo. He

expressed feelings of urgency for his brother and friends to quickly prepare to

leave Nauvoo. He desired that his

property be sold and the funds be used to help others to join the trek across

Iowa.

“I feel as though

Nauvoo will be filled with all manner of abominations. It is no place for the Saints, and the

Spirit whispers to me that the brethren had better get away as fast as they

can.” He doubted that any of the Twelve

would be returning to Nauvoo any time soon.

He commented on the recent events in Nauvoo including the outrageous

rumor that he had been shot. “We have

the most perfect peace that ever a Camp had.”

At 10 p.m., Pamela,

wife of Ezra T. Benson gave birth to Isabella Benson. It was raining very hard at the time. They had to raise her bed on brush to keep her away from the

water in the tent.

Pigeons

were seen flying in large numbers to the north. The Nauvoo Brass Band (another band, separate from William Pitt's

band) played for the 25th Quorum of Seventies.

A son, Hyrum Smith

Church, was born to Hayden and Sarah Church.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 71‑72; Black, Membership of the Church

1830‑1848; “Hosea Stout Diary”; The Orson Pratt Journals; The

Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 22, 118‑19; T. Edgar Lyon, BYU

Studies, 18:2:167; History of the Church, 7:610; Ezra Benson

Autobiography, Instructor 80 (1945), 216; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” 59

Warm rain

continued to fall in the morning. At 7

a.m., the temperature was fifty degrees.

Many more teams rolled into camp during the day including the families

of Thomas Grover, John Gheen and Theodore Turley. The brethren husked over one hundred bushels of corn in order to

pay for corn and fodder.

At 1 p.m., the band

started toward Keosauqua in carriages for their concert. After a ten-mile journey to the east, they

arrived in town at about 3 p.m. and were requested to go through the town to

play at different stopping points. A

grocery store keeper asked them to play, and he then graciously invited them in

to choose a treat of anything in the store.

Other store keepers did the same.

The procession then marched up to the Des Moines hotel and courthouse,

where supper had been prepared for them.

At 7 p.m., they gave a concert in the courthouse which lasted until

9:30. The audience was extremely

pleased and gave loud applause. They

were paid $25.70 and invited to play again the following evening. After an exhausting, but rewarding visit to

Keosauqua, the band started back to camp after 10 p.m., arriving at about 1

a.m.

During the day, the

Camp of Israel at Richardson Point was very uncomfortable because of the

rain. Hosea Stout's tent leaked badly,

making it very difficult to keep dry.

During the day a quail landed on top of the Stouts’ tent and fluttered

down in the tent door. Brother Stout

picked the bird up and thought about the account in the Bible (Numbers 11:31‑33)

when the Lord sent thousands of quail into the Camp of Israel. After the children of Israel ate the quail,

the Lord smote them with sickness.

Brother Stout felt that this quail had not been sent in wrath, so he

cooked it. It proved to be a wonderful

blessing, and a nice meal.

Eliza Lyman wrote:

“We tried to dry our clothes, but one side got wet while the other was getting

dry. It rained all day and it was

almost impossible for us to get anything to eat.”

Sickness in the

various camps continued to be of great concern. Isaac Chase was sick at Richardson's Point. Brigham Young's nephew, Edwin Little, was

feeling somewhat better. Daniel and

Orson Spencer were camping about ten miles back at Indian Creek with Orson

Spencer's wife, Catherine, who was critically sick. Her little children would ask at the door of the wagon, “How is

mamma? Is she better?” Catherine would turn to her husband and say, “Oh you

dear little children, how I do hope you may fall into kind hands when I am

gone.” She told her husband on this night that a heavenly messenger appeared to

her and told her that she had suffered enough, that he had come to convey her

to a mansion of gold. The continual

rain made it impossible to keep her bedding dry and comfortable, but her

husband sat by her side, doing his best to keep the rain and cold away from

her. Friends held milk pans over her

bed to keep her dry.

Albert P. Rockwood's

wife, Nancy, presented him with a hat made of straw gathered from the horse

feed.

Elder Willard

Richards wrote to Sheriff Jacob B. Backenstos.

Elder Richards, who was the church historian, asked him to send a list

of the Carthage Greys and other names of members of the mob in Hancock

County. He wished to add these names to

the history of the Church.

Orson Pratt left

Richardson Point and traveled about eleven miles on very muddy roads in the

rain, attempting to join Parley P. Pratt's forward group. He camped about two miles north of

Bloomfield, on the north side of the Fox River. Parley P. Pratt and George Miller were camping about one mile

east of Bloomfield. Part of George A.

Smith’s and Amasa Lyman’s companies also moved out of camp.

A party was held at

Fox River, four miles to the west, at the home of Brother Stewart. About twenty brethren attended.

It was

also a rainy day in Nauvoo, fifty‑five miles to the east. The state troops came into the city

providing protection for Francis M. Higbee.17

John E. Page, William

Smith and Hiram Statton (a Strangite) held a council meeting at Page's home.

A daughter, Isabell

Wardrobe, was born to John and Lucy Wardrobe.

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 76‑7; Aurelia Spencer Rogers, “Life

Sketches.”; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 132‑33; The Orson

Pratt Journals; William Clayton’s Journal; Brooks, The Diary of

Hosea Stout; “Mosiah Hancock Autobiography”, typescript, 31; “Thomas

Bullock Journal,” 59; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848; Memoirs

of John R. Young, Utah Pioneer 1847, 18; “William Huntington

autobiography,” typescript, 49; Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman, Pioneer, 150

Light rain

showers fell during the morning. The

rain and muddy roads continued to put a halt to any movement of the camp.

The band left camp at

about 11 a.m. to put on another performance at Keosauqua. The traveling was very unpleasant in the

rain and William Pitt had a severe chill all the way. When they arrived at Keosauqua, they were again welcomed warmly

by the citizens of the town. The

courthouse was filled. They received

$20.00 for the concert and returned to camp at about 3 a.m.

Brigham Young's

nephew, Edwin Little continued to be very sick and was taken to a nearby house

in Brigham Young's carriage. There were

also four cases of measles and one case of mumps reported in the camp.

Eliza R. Snow was not

feeling well because of the dampness.

For dinner, her good friend Hannah Markham brought her “a slice of

beautiful, white light bread and butter, that would have done honor to a more

convenient bakery, than an out‑of‑door fire in the wilderness.”

At 2 p.m., a heavy

rain shower started which continued for two hours. The skies then cleared and the moon shined bright in the

evening. Brigham Young and Willard

Richards spent the evening with George A. Smith in his tent.

Hosea Stout rode

around the camp and found Henry G. Sherwood surveying and taking compass

readings of the spot where the cannon balls had been buried. They had been buried in a hole near the

roots, on the west side of a white oak tree.

Brother Sherwood calculated that the distance from Nauvoo to that spot

was fifty-five and one quarter miles.

There was a problem

in the portion of the camp that had gone on ahead. James M. Hemmick of the pioneers challenged Wilbur J. Earl to

fight a duel. This was reported back to

Brigham Young.

Most of the camp

retired to wet bedding at night.

To the

west of Richardson's Point, about seventeen miles ahead, George Miller and

Parley P. Pratt moved their camp about twenty‑eight miles further to the west of Chariton River.

Catherine

Spencer continued to be critically sick at the Spencer camp, ten miles to the

east of Richardson’s Point at Indian Creek.

She called her husband and children to her bedside to give them a

parting kiss. She then said, “I love

you more than ever, but you must let me go.

I only want to live for your sake and that of our children.” She was asked if she had any message for her

father's family, to which she replied, “Charge them to obey the gospel.” The rain provided much discomfort and she

finally expressed a desire to be in a house.

A man by the name of Barnes, living nearby, consented to have her be

brought to his house.

Further

back, at the Des Moines River, many Saints were struggling to catch up with the

main camp. The river was swollen and a

ferry was being used to transfer the wagons and teams across. Long waits were experienced for their turns

to cross.

Many

brethren were still very busy making wagons, but were hindered because of the

wet weather.

Luke S. Johnson,

again a member of the Church, left for Kirtland to retrieve his family. Before he left, he called on John E. Page,

who he did not know was following after James Strang. Brother Johnson asked Page if he knew who he (Johnson) was. “No,” replied Page. Brother Johnson said, “You are my successor

in office [in the Twelve] and I am come to call you to an account for your

stewardship.” Page blushed and hung his

head.

A daughter, Clara

Lucinda Jones, was born to Nathaniel and Rebecca Jones.18

Also born was a son, Charles Drown Rollins, to Enoch and Sophia Rollins.19

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 77, 80, 81; John D. Lee Journal, March 14,

1846; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout; Aurelia Spencer Rogers, “Life

Sketches”; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 133‑34; Beecher, The

Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 119; William Clayton’s Journal;

Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848; “Journal Priddy Meeks,”

typescript, 7‑8; Bruce Van Orden, Church News, March 8, 1996;

“Warren Foote Autobiography,” typescript, 77; Watson, The Orson Pratt

Journals

The skies

were cloudy all day, with occasional rain showers in the afternoon. But in general, the weather was much better

and the mud was drying up. At 8 a.m.,

the temperature was forty‑one degrees.

Several teams, including those belonging to the band, moved in the

morning to a dryer location, one quarter mile to the south.

Several of the

brethren left the camp to return to Nauvoo.

William Jepson was returning and volunteered to carry another load from

Nauvoo for Patriarch John Smith. Daniel

Carn20 and Jeremiah Root

returned to get their families.

They took back an order for the

Nauvoo Trustees to provide additional teams to the Carn and Root families. They also carried back sixty letters, an

order for a telescope, sextant, barometer and other items to be sent by water

to Council Bluffs.

There was plenty of

corn and hay in the camp because of all the recent labor performed by the brethren. Many continued to work, even in the pouring

rain.

At 5 p.m., Brigham

Young met with Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards in Elder Richards'

tent. They discussed the dispute of the

day before, when James Hemmick challenged Wilbur Earl to fight a duel. They composed an order to discharge Brother

Hemmick from his duties in the pioneer company. At 6 p.m., Stephen Markham took the order to Brother Hemmick who

had gone on ahead. Brother Hemmick did

not want to leave the Saints and appeared to regret his actions.

At 7 p.m., Levi

Stewart arrived from Nauvoo bringing thirty‑four letters. One of the letters was to Brigham Young from

Orson Hyde, relaying the recent news regarding Luke Johnson, John E. Page, and

William Smith. Brigham Young spent the

evening with Heber C. Kimball, George A. Smith, and Willard Richards reading

letters.

Sadly,

Sister Catherine Spencer died at the age of thirty‑four. She left this world in peace, with a smile

on her face, and her hand held by her husband, Orson. The Spencer family started the trek back to Nauvoo for her

burial.21

A son,

Jeremiah Albert Robey, was born to Jeremiah and Ruth Robey.22

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 79‑81; Aurelia Spencer Rogers, “Life

Sketches”; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 134‑35; William’s

Clayton Journal; Black, Membership of the Church 1830‑1848;

Watson, The Orson Pratt Journals; “William Huntington autobiography,”

typescript, 49; Far West Record, 252

There were

several rain showers over night, and in the morning snow flurries fell. The weather cleared up during the day. The creeks nearby were so swollen with water

that they could not be crossed. During

the night, Eliza R. Snow's tent blew down and spilled a pail of potato soup

which was intended for breakfast.

Instead, she ate fried jole (either fish heads or the jowls of pork or

beef) and jonny cake (cornmeal bread).

Brother Isaac Chase

was very sick with “lung fever,” and was moved to a nearby house. There were several other cases of this fever

in the camp, but in general the Saints were in very good health, considering

the circumstances. News of Sister

Catherine Spencer's death spread through the camp and many spent the day

mourning the loss.23

At 10 a.m., Brigham

Young and other members of the Twelve met with John Smith and Bishop Newel K.

Whitney in Willard Richards' tent. They

decided to sell hardware and crockery to lighten the loads and to obtain more

teams. President Young was constantly

advising the brethren to lighten their loads for travel over muddy roads. On one occasion, Ezra T. Benson went to

Brigham Young informing the president that he could not continue on because of

the heaviness of his load and the weakness of his teams. Brother Benson was willing to wait until he

could go further. Brigham Young asked

what was loaded on the wagon. Brother

Benson replied, “Six hundred pounds of flour and a few bushels of meal.” President Young said, “Bring your flour and

meal to my camp, and I will lighten you up.”

Brother Benson appreciated the offer to help and did as he was

advised. To his surprise, Brigham Young

requested John D. Lee to weigh out the flour and divide it among the camps,

leaving Brother Benson with only fifty pounds of flour and a half a bushel of

meal for his family. But when it came

time to move on, Brother Benson's wagon rolled comfortably along. When he saw others sink to their axles in

the mud, he would tell them, “Go to Brother Brigham, and he will lighten your

loads.”

President Young was

concerned about the forward groups of Parley P. Pratt, Orson Pratt and George

Miller. He wrote a letter advising them

to remain where they were until the rest of the camp caught up with them, if

they were able to buy cheap grain where they were located. He counseled them to not sell useful

provisions.

The camp was also

concerned about the pioneers who had been left to complete jobs at the Reed

Creek camp, on the other side of the Des Moines River. Many were without food and needed help to rejoin

the main camp. Meat and other

provisions were obtained and sent back for the pioneers.

Another council

meeting was held at 5 p.m., attended also by the captains of the pioneers and

guard. They were asked to obtain the

names of the men in their charge, who wanted to return to Nauvoo for their

families. Those going back were to

leave their teams in the camp and to find other teams in Nauvoo. They would be credited the value of their

teams in camp and be given an order for the Trustees in Nauvoo for

assistance. Later in the evening,

Brigham Young met with several brethren who were about to return to Nauvoo.

There were many

people from nearby farms who came into camp, interested in exchanging oxen for

horses. It had been decided to exchange

many of the horses for oxen because the oxen would endure the journey

better. Most of the citizens wanted to

trade one yoke of oxen for a good horse which was really worth two yokes of

oxen. Because of the high price, few

trades were made. Three or four cases

of distemper were discovered among the horses in camp.

George

Edmunds, a lawyer, invited William Smith to study law under him if William

would drop all of his beliefs in the gospel.

The editor of the Illinois

State Register wrote: “The

universal desire [of the Mormons] seems to be to get away to a land of peace.”

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 81‑83; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout;

“Ezra Benson Autobiography,” Instructor 80 (1945), 216; Watson, The

Orson Pratt Journals; Beecher, The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow,

199, 276; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” 60; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness 139;

Memoirs of John R. Young, Utah Pioneer 1847, 18; Esshom, Pioneers and

Prominent Men of Utah, 800;

Holzapfel, Women of Nauvoo, 177

The

morning was clear, windy and colder, becoming cloudy in the afternoon. At 8 a.m. the temperature was thirty‑six

degrees. There were a few cases of

dysentery reported in the camp. Willard

Richards was sick in bed again.

Reynolds Cahoon had been thrown from his wagon and dislocated his

shoulder.

At 8 a.m., members of

the Twelve and Bishop Whitney met at Willard Richards' tent. It was reported that Shadrach Roundy and his

company were fourteen miles ahead on some property occupied by a Widow Evans. Orson Pratt and others were seventeen miles

ahead. Bishop Miller and Parley P.

Pratt were believed to be forty‑five miles ahead on the Chariton

River. The Council closed with music

and songs by Brothers Kay and Hutchinson at 10 a.m.

There was a lot of

activity in the guard and pioneer companies to determine who needed to return

to Nauvoo for their families. In all,

about fifty‑five men decided to return, including thirty of the

guard. These men were given “honorable

releases.” They were told to leave

their teams in camp. Lorenzo Young and

Stephen Markham were kept busy appraising value of each team so the brethren

could be reimbursed back in Nauvoo. There

was some murmuring regarding this policy.

One brother swore that he would not give up his father's team, but would

sooner poison the horses. His team was

put under a special guard.

In the late

afternoon, Hosea Stout traveled to William Clayton's camp24 to have Brother Clayton write the

reimbursement orders to the Nauvoo Trustees.

It took longer than expected, well into the night. Hosea Stout had to return on a dark road to

the main camp. Brother Clayton sent a

man with a lantern to help light the way until Brother Stout reached the edge

of the prairie. Then, without a light, and

in pouring rain, he had to wade a considerable distance in deep mud and

water. He finally waded his way to

Brigham Young's tent with the orders which he left for signature. He was then met by a man who claimed that

President Young had given him permission to take a team back to Nauvoo. Brother Stout could see through this

dishonest statement and took the team into his charge.

Eliza R. Snow had

spent the day washing clothes at the creek.

In the evening, Brigham Young came in a buggy to take Sister Snow and

others to a dinner prepared by Sister Young.

It was a glorious feast of pot‑pie made from wild game: rabbits,

pheasants, quail, and other animals.

The rain finally

stopped. That night, Eliza R. Snow was

very glad to see the moon shining on the wagon cover a few inches above her

head.

During the

day, William Hall left camp with his team, and headed for the Des Moines River

to bring forward one of Allen Stout's loads.

Brother Stout had been sick with sore eyes and was trying to catch up

with the camp. While Brother Hall was

at Indian Creek, one of his horses became very sick with bloating and

colic. Elders Hall and Lluellen Mantle

decided to lay hands on the horse and bless it. The horse recovered immediately and went on for about two more

miles and then was again attacked with pain.

They tried unsuccessfully to give it medicine. The horse lay on its side.

Reuben Strong believed it was still alive and proposed to lay hands upon

it again. A discussion ensued. Some felt that it was not proper to use the

priesthood to bless a horse. Elder Hall

justified the action with the prophecy of Joel, “that I will pour out my spirit

upon all flesh” (Joel 2: 28). This

satisfied the brethren and they laid hands on the horse, commanding the unclean

and fouls spirits to depart and go to Warsaw, Illinois (home of the mob). The horse rolled over twice, sprang to its

feet, vomited, and by the next morning was performing work as usual.

In the

morning, Elder Orson Hyde, while troubled by seeing many follow after false

prophets, received an important revelation from the Lord that was published in

Nauvoo. The Lord told him that evil men

would try to divide the flock. These

men were not following after the Lord,

Yet they are

instruments in my hands and are permitted to try my people, and to collect from

among them those who are not the elect, and such as are unworthy of eternal

life. . . . My people know my voice and also the voice of my spirit, and a

stranger they will not follow. . . . Behold, James J. Strang hath cursed my

people by his own spirit and not by mine.

Never, at any time, have I appointed that wicked man to lead my people.

. . . But his spirit and ambition shall soon fail him and then shall he be

called to judgment and receive that portion which is his mete. . . . Let my

Saints gather up with all consistent speed and remove westward. Let there be no more disputes or contentions

among you about doctrine or principles, neither who shall be greatest. . . .

The thoughts of many

of the Saints were focused on the anticipated journey west. While lying in his bed, Thomas Bullock saw a

vision:

Last night

while lying in my bed, comfortable, I saw a vast range of mountains. A river

had been crossed and I saw the waggons pass up round a mountain into the hollow

of a hill, and again come round the other side of the defile and ascend the

road up the other side of the mountain. The waggons appeared to me to be about

8 or 10 rods in advance of each other and the cavalcade must have been several

miles in length. The tops of the mountains appeared to reach the clouds, almost

perpendicularly, while beneath the road was an immense precipice. The road

appeared scarce wide enough for the waggons to pass, being very narrow. The

waggon covers appeared a deal darker, as if they were dirty with use. I

involuntarily rose up in my bed and discovered it was a vision and not real.

Warren Foote wrote a

letter to his nonmember brothers showing that the Saints had a better

understanding where they would be heading: “We expect to start west the latter

part of April. We are not going to

Vancouver Island [Canada] (it had been reported that we were going to Vancouver

Island), nor to California. We shall

probably settle in the Rocky Mountains. . . . One company has gone and another

will start in April.”

Watson, Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 83, 84; Brooks, The Diary of Hosea Stout;

Watson, The Orson Pratt Journals; Beecher, The Personal Writings of

Eliza R. Snow, 120; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” 60, 61; “Warren Foote

Autobiography,” typescript, 79-80; “Isaac Haight Autobiography,” typescript,

28; “John D. Lee Journal”; Millennial Star, 7:10, May 15, 1846, 157‑58

The

weather was cold with strong winds that capsized several tents. Sister Eliza R. Snow's tent kept blowing

over so she remained in the wagon for the entire day. Hannah Markham made the wagon comfortable with hot coals.

At noon, a public

Sabbath meeting was held. Elder Truman

Gillet and Henry G. Sherwood addressed the assembly on the first principles of

the gospel. There were many nonmembers

present who were offering oxen in exchange for horses. Some of the brethren declined to trade on

the Sabbath.

At 7 p.m., a council

meeting was held in Willard Richards' tent.

Brigham Young asked that an epistle be written on the following day, to

the Church in Nauvoo. They also wrote a

letter to the Trustees in Nauvoo. There

had been problems and some hard feelings regarding property ownership. The Trustees were asked to make a careful

record of transactions made by the Church on behalf of others. These sales, and a description of the

payment received, must be carefully entered into the record books. A copy of the entries should be sent to the

camp to help avoid further confusion.

A letter was also

written to Edward Duzette, who had served as the drum major for the Nauvoo

Legion Band. Brother Duzette was

instructed to come to the camp and bring with him the flags belonging to the

Nauvoo Legion. The tent of Willard

Richards was designated as the general post office. Elder Richards would serve as post master for the traveling camp.

Hosea Stout tried to

bring more order to the company of guards.

He told them to quit running to Brigham Young for advice and counsel on

matters which had been already settled.

When some of the men disagreed with Brother Stout, they would go to

Brigham Young hoping for a different answer.

President Young's counsel usually was the same counsel that Brother

Stout had originally given.

John

Taylor came to visit Charles C. Rich's family, who were camping four miles to

the west, on the Fox River. Brother

Rich had been working on a job making shingles for a farmer. Elder Taylor told them what they could

expect on the journey ahead. He said

that if they would be humble and patient, all would be right. Afterwards, Elder Taylor ate dinner with the

family and cheered them up with “his lovely jokes.”

Many of

the Saints, back in Nauvoo, experienced a spiritual “Day of Pentecost.” Elder Orson Hyde spoke to a large

congregation assembled in the temple and read the revelation that he had

received the previous day. He mentioned

that he had passed John E. Page in the morning. Page told him that he had received a revelation and said it

“makes me ashamed of myself and ashamed of my God.” Those in the congregation received testimony that when a man

falls from great light, he falls into great darkness. After the meeting, Rufus Beach25

confessed his error in believing Strangism.

In the afternoon, at

the Seventies Hall, Joseph Young and Benjamin L. Clapp spoke. At sundown, fourteen people gathered in the

temple to partake of the sacrament.

Some of the brethren spoke in tongues, others prophesied. While a brother related a vision, a light

was seen over his head. The face of

another brother shone with great brightness.

Two heavenly beings were seen in the northeast corner of the room and

the Holy Ghost rested on all present.

This spiritual meeting continued until midnight. Thomas Bullock said it “was the most

profitable, happy, and glorious meeting I had ever attended in my life.”