Wednesday, July 1, 1846

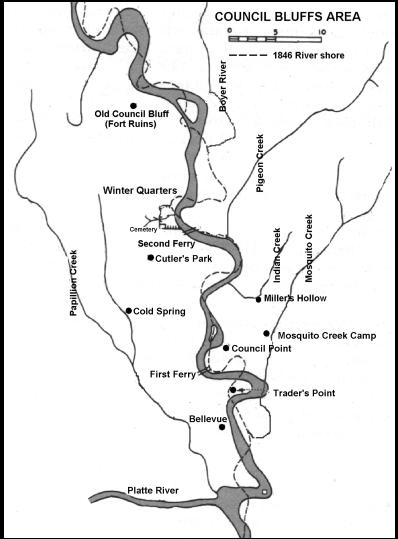

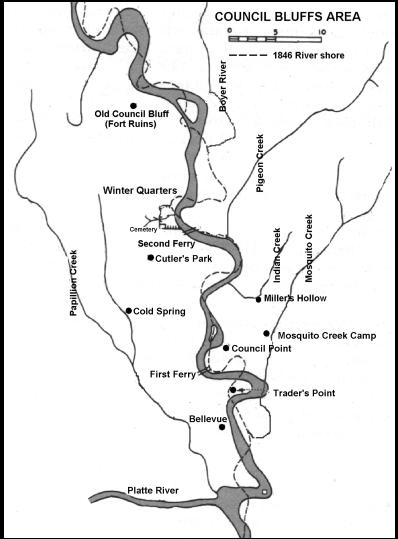

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

In the

morning, Brigham Young and other members of the Twelve rode up the bluffs to

John Taylor’s camp on Mosquito Creek, where they met together with Captain

James Allen and his men from Fort Leavenworth.

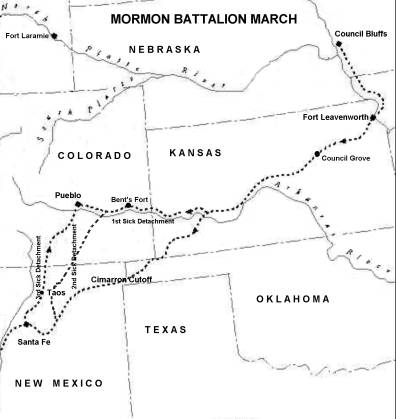

Captain Allen presented a letter of introduction from President William

Huntington at Mount Pisgah. He also

showed the brethren a letter from Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, authorizing

Captain Allen to recruit Mormons for a battalion to march toward Santa Fe. The decision had already been made by the

brethren the previous evening to support the government and raise the

battalion.

At 10:40

a.m., the council called the men in the camp to assemble. They gathered around a wagon used as a

stand. President Young introduced

Captain Allen, who then addressed the people.

He explained that his mission, authorized by the President of the United

States, was to enlist five hundred

Mormon men into a battalion to help take California in the Mexican War. He wanted the men to be ready to leave in

ten days. If he could not get five

hundred men, he did not want any. He

read his orders and passed out copies of a circular which had also been passed

out at Mount Pisgah.

President

Brigham Young next addressed the assembly.

The men were very anxious to know the feelings of the brethren on this

matter. President Young explained that

this call to service was something that he had been hoping for and that it

would bring about much good. He probably

explained about Jesse C. Little’s mission to Washington D.C. to enlist support

from the government.

There were

very bitter feelings in the hearts of the men toward the government for past

injustices. But President Young tried

to help them make a distinction between the general government and those in

public positions who oppressed the Saints in Missouri and Illinois. The government in general should not be

blamed for acts perpetrated by the mob.

He said, “The question might be asked, is it prudent for us to enlist to

defend our country? If we answer in the affirmative, all are ready to go. . . .

If we embrace this offer we will have the United States to back us and have an

opportunity of showing our loyalty and fight for the country that we expect to

have for our homes.”

President

Young next issued the call to raise the Mormon Battalion: “Now I want you men to go and all that can

go, young or married. I will see that

their families are taken care of; they shall go on as far as mine, and fare the

same, and if they wish it, they shall go to Grand Island first.”

Captain

Allen stated that he would write to President Polk and ask that permission be

granted to let the rest of the camp stay in Indian Territory while the

Battalion was away.

Elder

Heber C. Kimball formally proposed that the five hundred men be raised as asked

by the government. The motion was

unanimously supported by the brethren.

President Young immediately rose from his seat and said, “Come brethren,

let us volunteer.” Elder Willard

Richards started to take down names of volunteers.

The men in

the camp were still hesitant. Henry W.

Bigler wrote:

It was

against my feelings, and against the feeling of my brethren although we were

willing to obey counsel believing all things would work for the best in the

end. Still it looked hard when we called

to mind the mobbings and drivings, the killing of our leaders, the burning of

our homes and forcing us to leave the States and Uncle Sam take no notice of it

and then to call on us to help fight his battles.

Later,

members of the Twelve met in John Taylor’s tent to work out some of the details

with Captain Allen. There were good

feelings in the meeting. Brigham Young

proposed that he and Heber C. Kimball should travel to Mount Pisgah to raise

volunteers. He understood the urgency

to raise the Battalion. President Young

wished to have the rest of the camp settle on Grand Island for the winter while

the Twelve would travel further west with their families.

In the

afternoon Brigham Young and the others returned to their camp near the

river. Some of Brigham Young’s teams

had already been sent across the river.

President Young asked the Twelve to delay crossing over the river for

the present time.

Patty

Sessions recorded in her diary:

The boat

[ferry] is done, ready to cross. The word is for us to be ready to go to the

river at 10 o'clock. When 10 o'clock came the word was, put the teams to the

wagons and start in 10 minutes. Before that time was up the men were called to

a public council. One of the troops have come in to enlist men for one year to

go to California. The Twelve had a private council after and Brigham is going

back to Mt. Pisgah and sent word to us to stay where we were if we chose.

Lorenzo

Dow Young arrived back from his trading expedition to Missouri. He found the rest of his family well and

they were glad to see him.

A son,

Mason Lyman Tanner, was born to Sidney and Louisa Tanner.

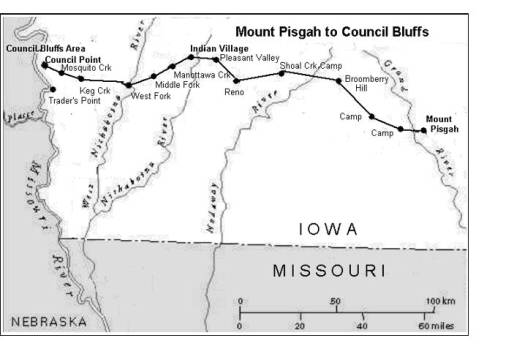

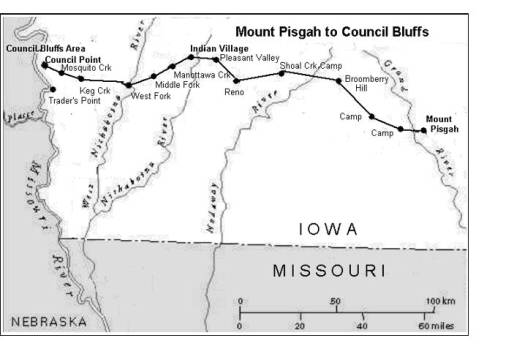

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

At 6 a.m.,

Parley P. Pratt, traveling back to Mount Pisgah, met William Clayton’s

company. Later in the morning, Wilford

Woodruff traveled a few miles and was also met by Elder Pratt, on his way to

raise a company of pioneers to go over the mountains. Elder Pratt of course had no idea that the plans and changed and

that now a battalion would be raised.

He delivered his message to Elder Woodruff’s camp of fifty wagons. Elder Woodruff traveled twenty miles this

day. William Clayton traveled seventeen

miles and remained a few miles ahead.

Further to

the west, near the Indian village, Hosea Stout and a large company returned to

work on a bridge. A new foreman was

selected and they decided to build a “drift bridge.” This bridge would be a large raft which was to be built on top of

the old bridge that had mostly been washed away. Many wagons were backed up at this point, waiting for the

bridge. Hosea Stout wrote, “Our

encampment now was very large. The

hills were full of our tents & waggons and seemed to be nearly as large as

the first camp when it started in February [at Sugar Creek].”

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

Sister

Mary Richards spent the morning unpacking her chest to let things air out, and

spent the rest of the day packing for her planned departure on the following

morning. She had been at Mount Pisgah

since June 12.

In the

afternoon, Parley P. Pratt arrived and called for a meeting at 5:30 p.m. He informed Ezra T. Benson that he had been

called to serve in the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, taking the place of John E.

Page. Isaac Morley was being sent to

take Elder Benson’s place in the presidency of Mount Pisgah. Elder Benson wrote:

Bro. Parley

P. Pratt came down from the Bluffs with a line from President Brigham Young,

directed to me, stating I was appointed one of the Twelve Apostles to take the

crown of John E. Page, and if I accepted of this office, I was to repair

immediately to Council Bluffs and prepare to go to the Rocky Mountains. A brother offered to take my family to the

Bluffs with his own team, and not owning a horse at this time, I went to see

Bro. Ross to buy one. He said he had

none to sell, but said if I was called to be on of the Twelve Apostles he would

give me one, and he turned out to be his best riding horse.

The

meeting was held and Elder Pratt called for a company of five hundred pioneers

to travel without their families over the mountains.

Bonaparte, Iowa:

Far to the

east, on the Des Moines River, a daughter, Mary Coltrin was born to Zebedee and

Mary Coltrin.

Sandwich Islands

(Hawaii):

The Brooklyn

raised anchor and again started to sail for California. The Orrin Smith family was left behind

because of illness. As they sailed, it soon discovered that they

had a stowaway. The stowaway was a

young lad from the U.S. Army.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 203‑207; “John Taylor’s Journal”; “Extracts

from the Journal of Henry W. Bigler,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 5:36;

Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 57‑8; Wilford Woodruff’s

Journal, 3:56; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly,

14:144; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

173; William Clayton’s Journal, 52; Beecher, ed., The Personal

Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 137 The Instructor, May 1945, 217; Rich, Ensign to the Nations, 32;

“Diary of Daniel Stark,” Our Pioneer Heritage 3:498; Ward ed., Winter

Quarters, The 1846‑1848; Life Writings of Mary Haskin Parker Richards,

67‑8; Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah, 1198; Jenson, LDS

Biographical Encyclopedia; Patty Sessions Diary in Our Pioneer Heritage,

2:61

Thursday, July 2, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

A general

meeting had been called at 10 a.m. near the river. This meeting was to further inform the Saints about the Mormon

Battalion and the leaders asked able men to step forward and enroll. John Taylor recorded in his journal that he

had hard feelings against the government.

However, he felt that the raising of the Mormon Battalion would give

them a legal right to go to California.

Captain

James Allen worked to secure the formal permission of the Pottawatomie Indians

for the Saints to settle on their lands.

The agreement read:

We the

undersigned chiefs and braves representing the Pottawattomie tribe of Indians

near this subagency do voluntarily consent that as many of the Mormon people

now in or to come into our country as may wish from cause or necessity or

convenience to make our lands a stopping place on their present emigration to

California may so stop, remain and make cultivation and improvement upon any

part of our lands not now cultivated or appropriated by ourselves, so long as

we remain in the possession of our present country, or so long as they shall

not give positive annoyance to our people.

Brigham

Young ate dinner with Patty Sessions.

He instructed her company to move down to Council Point, so they all

started preparing to make the move.

Brother Freeman came to get Patty Sessions to deliver his wife’s baby. She went back three miles to Parley P.

Pratt’s camp and helped deliver a baby girl into the Freeman family.

Brigham

Young finished taking his teams across the Missouri River on the ferry. A camp was established about four miles to

the west at Cold Spring. Lorenzo Dow Young also started taking his

teams over. When he learned that his

brother, Brigham, was making another trip with the ferry, he paid those running

the ferry extra money so that he could also finish taking his teams over. He wrote, “I went over and got back about

half after ten, tired almost to death.

I actually felt as if I had not strength enough left to undress

myself. Went to bed and rested as well

as I could, for the mosquitoes.”

Heber C.

Kimball and Willard Richards moved their camps further away from the river on

the east bank, and dug a ten-foot well, finding plenty of good water. Elder Kimball’s daughter, Helen Mar Kimball

Whitney wrote:

Mosquitoes

were so troublesome near the river that we were obliged to move back, and as we

were far from water, the brethren dug a well close by. As it was nearly dusk when they concluded to

move from the river, and being very weary, I, with one or two others accepted

an invitation from the Chief’s daughter to accompany her home; and when

returning, finding the wagons gone and not feeling strong, she urged me to

return and stop over night, which invitation I accepted though I spent a

somewhat nervous and wakeful night.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

With the

bridge finished, Hosea Stout attempted to cross it. There was a great rush to get across because everyone was afraid

that the poorly constructed bridge would not last. Brother Stout made it across and then

reached the next stream a mile further where another new bridge had just been

finished. He wrote:

There was

large companies of Indians followed us today for several miles and in fact they

thronged around us all the time we were building the bridge & at times

would come in droves to the camp but they were very civil, friendly & good‑natured

and done none of us any injury while we were here. They would amuse themselves sometime by swimming in the creek in

large numbers and sometimes at playing cards at which they seemed to be very

dexterous. They appeared to be much

interested at our operations while at work which seemed to be a great novelty

to them.

Brother

Stout moved on about 18 miles and camped in the prairie just after crossing a

small, deep stream.

William

Clayton lost his horses during the night.

He searched for them four miles to the east but could not find

them. He went back to his camp and

later found them a mile to the west.

His camp moved out about 10 a.m., passed through the Indian village at

sundown, and camped at the Nishnabotna River where the new bridge had been

built.

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

In the

morning, Parley P. Pratt and Ezra T. Benson started for Council Bluffs. Sarah Rich wrote that at about this time the

brethren in the settlement found that they needed to “stake and rider” the

fences in order to secure their crops from the cattle. She explained, “Now I expect that many of my

readers will not know what stake and rider fences mean, for they do not see

much of that kind of work in this day.

They put stakes cross ways on each end of their poles, and then laid

another pole on top of the old fence, which made the fence some higher than it

was so the cattle would not jump over the fence.”

Phinehas

Richards also departed with his family in one wagon. They had originally planned to stay at Mount Pisgah longer, but

Phinehas’ brother, Elder Willard Richards, asked them to move ahead to Council

Bluffs. They traveled about eight miles

on good roads and in pleasant weather.

To the west, on the

Oregon Trail, Nebraska:

The

Mississippi Company of Saints neared the North Fork of Platte River. During the night someone came into the camp

and cut loose several of the Saints’ horses.

By morning, three were missing.

During the morning, the Saints met a company from California who told

them the distressing news that there were no Mormons on the route ahead of

them. All this time, the Mississippi

Company thought they were behind the main body of the Saints. They now understood the truth, which caused

much dissatisfaction in the camp. Some

wanted to turn back, but they decided to press on to Fort Laramie.

Nauvoo, Illinois

Franklin

D. Richards and his brother Samuel W. Richards were preparing to leave for

their mission to England. At the

temple, Thomas Bullock pronounced a blessing on some important packages that

would be taken by these brethren to the east and to England.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 207; The Instructor, May 1945, 217; Woman’s

Exponent, 13:135, 150; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 195; William

Clayton’s Journal, 52; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of

Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 173; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 14:144; “John Taylor Journal,” typescript BYU;

Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church 3:143; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” BYU

Studies 31:1:74; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,” typescript BYU, 58; “John

Brown Journal,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:426; “Louisa Pratt

autobiography,” Heart Throbs of the West 8:241; Ward, ed., Winter

Quarters, 67; Patty Sessions Diary in Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:61

Friday, July 3,

1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Helen Mar

Kimball Whitney had spent the night with the Chief’s daughter. In the morning they both went out to pick

blackberries and other wild fruit in the woods. Helen was impressed by her new friend.

I learned

that her parents had separated, as her mother was now living with her and did

most of the work. Though dressed in her

native costume she looked neat and kept the house tidy, and could cook equal to

white women. . . . Later she showed her taste and skill in braiding my hair in

broad plaits, after the latest French style, and put it up ‘a la mode’! In the

evening she accompanied me to the Camp.

Many of

the men were busy moving their wagons across the river. Lorenzo Dow Young got up very early and

worked hard, driving teams up the bluffs on the west side of the river. Charles Decker soon arrived across the river

with four yoke of oxen to help Brother Young.

With an additional yoke of oxen, they hauled wagons up the hill. They could only haul up one wagon at a

time. At one point, one of the oxen

panicked and tipped over a wagon which contained some children. Luckily, the children were not hurt. They made several more trips with the help

of Jedediah M. Grant and camped near a small creek at Cold Spring.

Brigham

Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards started toward Mount Pisgah at 9

a.m. to raise men for the Mormon Battalion.

They rode in President Young’s carriage while other men in the party

rode on horseback. At 1 p.m., they

stopped at the Mosquito Creek camp and had dinner with George A. Smith, Orson

Pratt, and Orson Hyde. At 5 p.m., they

passed several companies traveling to Council Bluffs, numbering 180

wagons. After a thirty-four-mile

journey, they camped with Ebenezer Brown and John I. Barnard. The brethren talked with the men in the camp

about enlisting into the Battalion until midnight.

Zadoc Judd

was among those who heard President Young’s message to enlist. He wrote that they made

a request

that all who could possibly be spared should enlist as soldiers in the

government service to serve as such for the term of one year. This was quite a hard pill to swallow‑‑to

leave wives and children on the wild prairie, destitute and almost helpless,

having nothing to rely on only the kindness of neighbors, and go to fight the

battles of a government that had allowed some of its citizens to drive us from

our homes, but the word came from the right source and seemed to bring the

spirit of conviction of its truth with it and there was quite a number of our

company volunteered, myself and brother among them.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

William

Clayton’s company started early and traveled four miles before breakfast. As they traveled, they met Brigham Young’s

company and learned about their mission to recruit the Mormon Battalion. It was their belief that raising the

battalion would help the Church, and if the call to service was rejected, it

would bring more persecution upon the Church.

After they parted, William Clayton traveled a total of twenty‑five

miles, camping near Hiram Clark.

Further to

the east, after traveling twelve miles, Hosea Stout’s oxen could go no further

because of exhaustion. The other

brethren he was traveling with wanted to go on and did. Brother Stout was totally out of food and

pleaded with them to leave some with him for his family but they did not.

Brother Stout found a nice camp by a beautiful spring and soon other companies

joined him there. A man named Henry

Nebeker, who was not a member of the church, let Brother Stout get milk from

his cows and gave him a piece of bacon, and ten pounds of flour. By night there were many companies at the

campsite. Shortly after dark, members

of the camp saw a carriage and some horsemen coming from the west and feared

that the U.S. officers might be returning.

They soon found out it was Brigham Young and his company. President Young only stopped for a few

minutes to talk with Hosea Stout. He

explained about the mission to raise recruits for the Mormon Battalion at Mount

Pisgah and Garden Grove. Brother Stout

wrote, “Their presence seemed to give new life to all the camp who flocked

around them and asking so many questions that they could not answer any of

them. But after a few words of comfort

to us they went on.”

Still

further to the east, as Wilford Woodruff was traveling toward Council Bluffs,

he was overtaken by Parley P. Pratt and Ezra T. Benson. These brethren wanted Elder Woodruff to

return with them immediately to Council Bluffs. Elder Pratt was still following

his mission to raise a company of pioneers and then to quickly return to

Council Bluffs. Elder Woodruff decided

to join them, so he saddled his horse and off they went. He commented that he “had an interesting

time once more with Br. Parley. And to add to the interest of the days ride,

we passed through the main village of the Pottawatomie Indians the first time I

ever passed through a large village of Indians in my life.” They continued riding until dark and made

their beds in the grass on the side of a hill.

Soon the mosquitoes attacked them and they moved to the top of the hill where

the wind was blowing.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

Franklin

D. Richards and Samuel W. Richards boarded a steam boat, leaving Nauvoo for

their mission to England.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 207; William Clayton’s Journal, 52, 53; Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:56; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical

Quarterly, 14:144; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of

Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 173‑74; Woman’s Exponent, 13:135;

“Zadoc Judd Autobiography,” BYU, 21;

Saturday,

July 4, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

William

Clayton finally reached the camp at Council Bluffs. He was delayed for much of the day, searching for horses and

trying to find food for his hungry family.

He attended a council meeting at Captain Allen’s tent.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

Hosea

Stout continued his journey to Council Bluffs slowly because his teams were so

weak. The weather was hot and

muggy. He only traveled about six

miles, reaching Keg Creek, where there was a small grove. Here his oxen gave out again. After a rest in the afternoon, he continued

on for three more miles and camped on the prairie.

Further to

the east, and heading in the opposite direction, Brigham Young was in his

carriage ready to go at 8 a.m., when Elders Parley P. Pratt, Wilford Woodruff,

and Ezra T. Benson met him. Elder Woodruff had not seen President Young for

almost two years, as he had been away serving as the president of the British

Mission. He wrote, “It was truly a

happy meeting. I rejoiced to once more

strike hands with those noble men.”

Elder

Parley P. Pratt reported that he had raised a company of eighty-four pioneers

for the mountains. President Young

informed them about the new plans to raise the Mormon Battalion.

At 9 a.m.,

Parley P. Pratt continued his journey toward Council Bluffs. Since there was no longer an urgency for

Elders Woodruff and Benson to reach Council Bluffs, they joined Brigham Young’s

group, traveling back to Mount Pisgah where they would retrieve their families. After they had traveled twenty miles, they

found Elder Woodruff’s company. Brigham

Young met Elder Woodruff’s seventy-year-old father, Aphek Woodruff, for the

first time. Wilford Woodruff stayed

with his family then resumed his journey toward Council Bluffs. He rode fifty miles on this day and was very

sore, stiff, and sick.

At about a

half hour before sunset, Brigham Young’s group passed through Pottawatomie

Indian Village, pressed on for eight more miles, and spent the night in Isaac Morley’s camp. They counted 206 wagons during the day.

At 10:30

p.m., President Young retired for the night in Father Morley’s tent. It soon began to thunder, lightning and

rain. He had to crawl into a wagon to

avoid getting too wet. Many tents in

the area blew down during this hard downpour of rain.

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

A wedding

party was held with dancing and music, with “a thunderstorm to wind up the

celebration.”

Putnam County, on

the border of Iowa and Missouri:

A Mr. L.

Marshall wrote a letter to the President of the United States, “There is a set

of men denominating themselves Mormons hovering on our frontier, well armed,

justly considered, as depredating on our property, and in our opinion, British

emissaries, intending by insidious means to accomplish diabolical

purposes.” He asked for an armed force

to be sent to “expel them from our border.”

Nauvoo, Illinois:

Almon W.

Babbitt, one of the Nauvoo Trustees, took William Law on a tour through the

temple. Brother Babbitt had been a

longtime friend of Law’s, who was one

of the missionaries that introduced Brother Babbitt to the Gospel. This temple tour did not please many members

of the Church still in Nauvoo. Thomas

Bullock wrote, “Many persons expressed their dissent of the act and well do I

remember Joseph’s words, ‘If it were not for Brutus, Caesar might have lived.’

So has Law proved a Brutus unto Joseph.”

William Law had published the “Nauvoo Expositor” which was a catalyst to

the martyrdom of the Prophet.

Martha

Haven wrote to her mother in Sutton Massachusetts: “We think soon of going to Farmington, Iowa. We shall probably stay there till fall.” Her husband, Jesse, “talks of boxing our

things ready for the wilderness. . . . We have sold our place for a trifle to a

Baptist minister. All we got was a cow

and two pairs of steers, worth about sixty dollars in trade.”

Pacific Ocean:

The Saints

on the Brooklyn recognized Independence Day. Samuel Brannan brought out the cloth that he obtained at Honolulu

and had the women make it into uniforms for the men. Each man had a military cap and there were fifty Allen revolvers

available. Brother Brannan then drilled

the men with the help of Samuel Ladd, an ex‑soldier, and Robert Smith,

another passenger who understood military tactics.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 208‑9; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 174; “Diary of Lorenzo

Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 14:144; Wilford Woodruff’s

Journal, 3:57; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” BYU Studies, 31:1:74; Cook,

William Law, 117; “The Ship Brooklyn,” Our Pioneer Heritage

3:490; “Louisa Pratt Autobiography,” Heart Throbs of the West, 8:240;

Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion, 96; Holzaphel, Women of

Nauvoo, 173

Sunday, July 5, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

The

weather was extremely hot and muggy.

Lorenzo Dow Young wrote, “It seems as if we could not live.” Hosea Stout finally arrived at Council

Bluffs. He searched and found Elder

Orson Hyde who was the presiding Church official at the camp. Elder Hyde recognized Brother Stout’s

destitute condition and invited him to stay near his camp, which was on a

ridge. Brother Stout pitched his tent

and prepared for what he expected would be a long stay. In the evening he took his wife to be

reunited with her mother. He wrote,

“Our feeling on meeting was very tender without a word being said we all burst

into tears in remembrance of the loss of my little son Hosea.”

Hosea

Stout then went to see U.S. Captain James Allen, who was on another ridge

“situated under an artificial bowery near his tents with several men in

attendance having the ‘Striped Star Spangled Banner’ floating above them. He was a plain non-assuming man without that

proud over bearing strut and self conceited dignity which some call an officer‑like

appearance.” They had a pleasant

conversation about the battles that had occurred recently on the Rio Grande

River.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

During the

night, a White Hawk Chief named Oquakee came and camped near Brigham Young and

his company. They were hungry so

President Young asked a brother to give the Indians a fat cow. Brigham Young promised them another cow when

they returned to Council Bluffs. The

Indians, were of course, very pleased.

At 8:30

a.m., Brigham Young’s company resumed their journey toward Mount Pisgah. At 11:30 a.m., they stopped when they came

upon a number of brethren. Brigham

Young preached and continued recruiting for the battalion, but he sensed that

it had little effect. He reproved

Andrew H. Perkins for harboring a wrong spirit in his company, to which Brother

Perkins responded to with gratitude.

Samuel H.

Rogers reflected on reasons to join the Battalion, “It was like a ram caught in

a thicket and that it would be better to sacrifice the ram than to have Isaac

die. Reflecting upon the subject, it

came to my mind that Isaac, in the figure, represented the church . . . and for

the saving of its life I was willing to go on this expedition.”

At this

location was the Phinehas Richards’ company, including Mary Richards. President Young asked Mary Richards if her

husband, Samuel W. Richards, had left Nauvoo for his mission to England. She told him that she believed that he

had. President Young was pleased. He asked her if it had been hard to part

with him and how she was doing. She

responded: “[I] told him it was hard and I stood it the best I could being

satisfied that I had to endure it. I did

the best I know how.” Elder Kimball

also remarked that he was pleased that Samuel W. Richards had gone on the

mission and said that he was a good boy.

Mary wrote: “[They] told me to

be a good girl and it would only be a little while before I should meet him on

the other side of the Rocky Mountains.”

Willard

Richards, Samuel’s uncle, also visited with Mary Richards and the rest of the

family. He mentioned that if Samuel W.

Richards and Franklin D. Richards had not left for their missions, they would have

been asked to join the Mormon Battalion.

A third brother, Joseph, was being counseled to join the battalion as a

drummer. Mary shared with Willard

Richards her trials and asked for a blessing.

He replied, “You have got your hearts desire and there is every blessing

in the world for you and what do you ask more?” He gave them some good instruction and had to leave them at 4

p.m.

Brigham

Young’s company continued their journey.

During the day they counted 240 wagons.

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

Jesse C.

Little arrived at the settlement on his way to deliver the news regarding the

battalion from President Polk to Brigham Young. Certainly he discovered that Captain Allen

had already been to Mount Pisgah on this mission. He went to the wagon of Louisa Pratt and delivered to her some

money from her husband, Addison Pratt, who was serving a mission in the South

Pacific.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

Meetings

were held in the temple. Almon Babbitt

spoke in the morning and Joseph Young spoke in the afternoon. He spoke against abusing wives, children,

and animals. Erastus Snow left Nauvoo

for his trip back to join his family whom he had left at Garden Grove. Brother Snow had earlier returned to Nauvoo

to try to sell his property. He did so,

for about one fourth the real property value.

On this day he crossed the Mississippi with his brothers William and

Willard Snow.

A

daughter, Barbara Young Crockett, was born to David and Lydia Crockett.

California:

With the

aid of American settlers in the vicinity of Yerba Buena (San Francisco) Colonel

John C. Fremont defeated the Mexicans recently in two battles. On this day, the American Californians

declared themselves independent, and placed Fremont as their leader.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 209; “Samuel H. Rogers Journal”; “Diary of

Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 14:144; Brooks, ed., On

the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 174‑75;

Beecher, ed., The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 138; Roberts,

Comprehensive History of the Church, 3:380‑81; Donna Hopkins Scott, The

Crockett Family, 14e; “Thomas Bullock Journal,” BYU Studies,

31:1:75; Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:103‑15; “Louisa

Pratt Autobiography,” Heart Throbs of the West 8:240; Ward ed.,

Winter Quarters, 68, 76

Monday, July 6, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Hosea

Stout went to Trader’s Point, a little town on the Missouri River, a few miles

downriver from the ferry crossing. He

described it as an “Indian village which consisted of some scattering houses

and was mixed up with French & half breeds. All not amounting to many.

This was where they kept their trading houses & large business no

doubt is carried on.”

At the

river crossing, many were moving their wagons over to the other side. It was hard work and very slow going. George Miller crossed over with thirty-two

wagons. He was going 114 miles west

Pawnee Village, a Presbyterian mission station which was recently raided by

Sioux Indians. His mission was to go to the village,

salvage any possessions, and bring them back to Bellevue, which was across the

river from Trader’s Point.

Hosea

Stout went for a visit across the river.

“The hill is uncommonly steep on the other side. The landing was at the mouth of a deep

ravine up which it was now contemplated to make a road as it would not then be

a very steep hill to assend.” He went

with Orson Pratt, George A. Smith, and others to find a good route for the

proposed road. It would be very

difficult to make because the area was heavily timbered and there were very

many ravines.

On his way

home, Hosea Stout met George W. Harris.

They had a long talk and Brother Harris advised him to enlist in the

Mormon Battalion. Brother Stout wrote,

“I then returned home again as I went not yet knowing what to do.”

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, Iowa:

Wilford

Woodruff continued his journey toward Council Bluffs. An Indian chief and some squaws camped nearby that evening. The chief said that he was going to meet

with Mormons and “smoke the pipe of peace.”

Near Mount Pisgah,

Iowa:

Brigham

Young and his company arose very early, at 4 a.m., and were on the road by

4:30. They stopped for breakfast at

Ezra Chase’s camp. Eleven miles outside

of Mount Pisgah, they met Charles C. Rich and Jesse C. Little, who joined their

company. As they passed Daniel

Russell’s camp, they blessed his sick wife. In the evening they reached Mount

Pisgah. During the day they passed 241

wagons, including 63 that were camping across the river from Mount Pisgah. They had counted a total of 800 wagons and

carriages between Council Bluffs and Mount Pisgah. Brigham Young spent the night at President William Huntington’s

house.

Chimney Rock,

Nebraska:

The

Mississippi company of Saints came to Chimney Rock. They stopped at Horse Creek and repaired wagons.

Voree, Wisconsin:

James J.

Strang, who claimed to be Joseph Smith’s true successor, was proclaimed

“imperial primate.” John C. Bennett, a

former counselor to Joseph Smith, was named Strang’s general‑in‑chief.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 209‑10; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 175; Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:57; William Clayton’s Journal, 53; Hartley, My

Best for the Kingdom, 210; Van Noord, King of Beaver Island, 49;

“John Brown Journal,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:426

Tuesday, July 7, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Hosea

Stout was looking for a way to get food for his family. He did not want to resort to begging, so he

went down Mosquito Creek to the sawmill and tried to find work. There was not any there and his health was

getting so poor that no one would have hired him anyway after taking a look at

him.

Thomas L.

Kane, the new influential non-Mormon friend, arrived at Council Bluffs from

Fort Leavenworth. Henry G. Boyle wrote,

While I was

waiting at Colonel Sarpy’s [trading post at Trader’s Point] for the Battalion

to be organized and mustered into service, a stranger (Colonel Kane) arrived at

the Point and obtained board and lodging at the same place. After gaining an introduction to me, he soon

entered into an animated conversation relative to our people, their history,

religion, etc. I found him to be a very

pleasant and affable gentleman, and very easy and fluent in conversation.

Brother

Boyle was at first cautious but Kane soon presented a letter of recommendation

from Jesse C. Little. “I soon found

that his sympathies and good feelings were all in our favor.”

Thomas L.

Kane later wrote about his first impressions of Council Bluffs:

They were

collected a little distance above the Pottawatomie Agency. The hills of the high prairie crowding in

upon the river at this point, and overhanging it, appear of an unusual and

commanding elevation. . . . This landing, and the large flat or bottom on the

east side of the river, were crowded with covered carts and wagons; and each

one of the Council Bluff hills opposite was crowded with its own great camp,

gay with bright canvas and alive with the busy stir of swarming occupants. In the clear blue morning air the smoke

streamed up from more than a thousand cooking fires. . . . From a single point

I counted four thousand head of cattle in view at one time. As I approached the camps, it seemed to me

that the children there were to prove still more numerous. Along a little creek I had to cross were

women in greater force . . . washing and rinsing all manner of white muslins,

red flannels and parti‑colored calicoes, and hanging them to bleach upon

a greater area of grass and bushes than we can display in Washington Square.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, in Iowa:

The day

was very hot. Wilford Woodruff

described, “Our cattle came near melting.”

He moved his camp within twelve miles of Council Bluffs.

Phinehas

Richards’ company was several miles behind.

Mary Richards wrote, “Having no wood, we started before breakfast, went

1 mile, found wood & stopped to take refreshments, after which we proceeded. Crossed several bad slews and hard

hills. The weather being very hot, we

rested from 11 till 3. Met about 40

Indians.”

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

At 10

a.m., Brigham Young dictated a letter to be sent to the Samuel Bent, the

president of the settlement at Garden Grove.

He sent him an advance message about the need for volunteers for the

Mormon Battalion. He explained that the

battalion would march to Fort Leavenworth to receive their arms, ammunition and

other provisions. He emphasized,

This is no

hoax. Elder Little, President of the

New England churches, is here also, direct from Washington, who has been to see

the President on the subject of emigrating the Saints to the western coast, and

confirms all that Capt. Allen has

stated to us. The U.S. want our

friendship, the President wants to do us good, and secure our confidence. The outfit of these five hundred men costs

us nothing, and their pay will be sufficient to take their families over the

mountains.

The

recruits were to be between age eighteen to forty‑five. They were to immediately go to Council

Bluffs. Drummers and fifers were

wanted. The rest of the Saints would be

gathering on Grand Island in the Platte River, about 120 miles to the west of

the Missouri River, where there was a salt spring which would be of use to make

salt. He anticipated that before

spring, they would be able to bring all of the Saints to Grand Island, even the

poor.

Brigham

Young and Heber C. Kimball conducted a meeting to raise the Mormon

Battalion. Heber C. Kimball said, “If

you leave your wives, your wives shall be taken care of . . . and if any of you

die, why die away and the work will go on.

I suppose that many think that you are going to starve to death. But I will tell you [that you] will never

want. You will have abundance and to

spare.” Jesse C. Little also spoke.

Sixty‑six

men volunteered. Eighteen-year-old

James S. Brown, was one of those who stepped forward. He had not as yet been baptized, but was so moved by the speaking

of Brigham Young that he went to Grand River and was baptized. He wrote in his memoirs:

This done

[my baptism], the happiest feeling of my life came over me. I thought I would to God that all the

inhabitants of the earth could experience what I had done as a witness of the

Gospel. It seemed to me that, if they

could see and feel as I did, the whole of humankind would join with us in one

grand brotherhood. . . . Elder [Ezra T.] Benson said the Spirit’s promptings to

me [to enlist] were right. . . . He told me to go on, saying I would be

blessed, my father would find no fault with me, his business would not suffer,

and I would never be sorry for the action I had taken or for my

enlistment. Every word he said to me

has been fulfilled to the very letter.

In the

afternoon, President Young wrote another letter, this one addressed to the

Nauvoo Trustees. He included one of

Captain Allen’s circulars asking for volunteers and wrote, “By this time you

will probably exclaim, is this Gospel? We answer, yes. We shall raise these five hundred men from

among those who are driving teams between this [Mount Pisgah] and Council

Bluffs.” He mentioned that there were

2,805 wagons between and including those points.

His main

purpose for this letter was to ask the Nauvoo Trustees to send all the men and

boys on the road to Council Bluffs immediately, leaving behind women and

children. These men would take the

place of those who would leave for the Battalion. The men were needed to move the camp to Grand Island, build

houses, and make hay. When they arrived

at Grand Island, they would unload and quickly return to Nauvoo to take all of

the Saints out of the city by fall. The

Trustees were encouraged to sell the temple, but not use the money to buy more

teams. Rather, it should be used to pay

off the temple hands and gather provisions.

They were instructed clearly to send Thomas Bullock and his family to

the camp immediately. Finally, he

mentioned that they received an offer to build a mill about fifteen miles north

of Council Bluffs on the east side of the Missouri River.

Monterey,

California:

Commodore

Sloat, in command of the United States squadron in the Pacific, bombarded and

captured Monterey, California

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 221‑26; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:57; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

176; “Juvenile Instructor,” 17:74; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 198, 99;

Brown, Life of a Pioneer, 22‑25; Roberts, Comprehensive History

of the Church 3:380‑81; “Mount Pisgah Journal,” July 7, 1846; Ward

ed., Winter Quarters, 67

Wednesday,

July 8, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

In his

quest to find a way to get food for his family, Hosea Stout started going

through all his things to select articles which he could take to the

settlements to trade for provisions.

However, his health was so poor that he knew that he would not be able

to go.

Keg Creek, Iowa:

Elder

Woodruff, twelve miles from Council Bluffs, went to bless Sister Mary Ann Grant

(wife of David Grant) who was in labor.

About five minutes later she gave birth to a daughter whom they named

Mary Ann Grant. He wrote, “Thus the

Saints bear children by the wayside like the Children of Israel in the

wilderness.”

Wilford

Woodruff saw about fifty Sioux Indians pass the camp, heading east. They said they were going to meet the Mormon

Chief. He supposed that they were

referring to Brigham Young who was at Mount Pisgah.

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

Brigham

Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards visited the Saints in Mount

Pisgah during the morning, encouraging and blessing them. They paid a visit to Lorenzo Snow. Brother Snow was counseled to leave Mount

Pisgah as soon as possible and to travel to the next planned settlement, Grand

Island. Lorenzo Snow asked what he

should do for provisions when he arrived there. President Young told him not to worry about that until he got

there. Lorenzo Snow had recently moved

into a house which had been used by Chandler Rogers, who went on to Council

Bluffs. Brother Snow wrote, “We had

suffered much inconvenience living in Tent and wagons in the hot weather.”

Those who

had already volunteered for the Mormon Battalion received some instructions

from Charles C. Rich, then started for Council Bluffs.

Willard

Richards administered to Sister Moss who had been bitten by a rattlesnake. Brigham Young spent the evening with Willard

Richards, Charles C. Rich, and Jesse C. Little.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 226‑27; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 176; Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:57‑8;

Beecher, ed., The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, 138; “Iowa

Journal of Lorenzo Snow,” BYU Studies 24:3:260; LDS Biographical

Encyclopedia. Jenson, Andrew, 4:705

Thursday,

July 9, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Wilford

Woodruff finally arrived at Council Bluffs, completing his long journey to

rejoin the main body of the Saints. His

journey began when he left his mission in England on January 23, 1846. He soon located the camps of other members

of the Twelve and enjoyed talking with Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor. Elder Woodruff pitched his tent on the bluff

near John Taylor’s camp.

The

brethren at Council Bluffs held a council meeting and wrote a letter to be

circulated throughout the camp, requesting volunteers for the Mormon Battalion.

Five

hundred men must be raised forthwith for the expedition to California. Don’t delay till the return of President

Young; but come forward hastily . . . for be assured it is the mind and will of

God that we should improve the opportunity which a kind providence has now

offered for us to secure a permanent home in that country, and thus lay a

foundation for a territorial or State Government, under the Constitution of the

United States. . . . The season is passing rapidly away; and it will take some

days to organize . . . and be assured that the Council and Camp will not move

from this place until this thing is done.

The

weather was very hot, but in the afternoon a cool and refreshing shower

fell. Anson Call, who had recently

arrived at Council Bluffs, lost another child.

His son, Moroni Call died.

Cold Spring Camp,

Nebraska:

Across the

Missouri at the Cold Spring camp, several of the men hauled in a load of poles

and bushes from which they made a fence and built a bowery.

George

Miller, joined by John Butler and other members of the James Emmett company,

left for their mission to journey 114 miles to the west. They were to go to the Pawnee Mission, which

had been recently destroyed by the Sioux Indians.

Mount Pisgah, Iowa:

At 11:30

a.m., Brigham Young and many of the other leaders were escorted to Alpheus

Cutler’s encampment and Brother Davis’ camp where President Young addressed the

brethren and ate dinner. At 2:40 p.m.,

the leaders left for Council Bluffs.

Their visit to Mount Pisgah had been good for the Saints there. Sarah Rich, the wife of Charles C. Rich

wrote, “Their visit to us at this time was encouraging, for they left a good

impression among the Saints which gave them new courage to preserve and prepare

themselves for what was ahead of them.”

At 5 p.m.

Brigham Young’s company rested their animals on the prairie for a time and then

continued until midnight after a journey of thirty miles. President Young and Heber C. Kimball slept

sitting up in the carriage.

Many of

the new recruits for the battalion were on their way to Council Bluffs. James S. Brown wrote,

We bade our

friends an affectionate farewell, and started on what we understood to be a

journey of one hundred and thirty‑eight miles [to the bluffs], to join

the army of the United States at our country’s call. We had provisions enough to put up to last us on our trip. . . .

Our initial trip was begun without a blanket to wrap ourselves in, as we

thought we could find shelter in the camps along the line of march. But in this we were mistaken, for everybody

seemed to have all they could do to shelter their own. The first night we camped on the bank of a

small stream, where we fell in with twelve or fifteen other volunteers who had not

so much as a bit of bread. . . . We divided with them, then scraped what leaves

we could and laid down thereon, with a chunk of wood for our pillow.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 226‑27, 589; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:58; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 14:145;

Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

176; Hartley, My Best for the Kingdom, 210; Brown, Life of a Pioneer,

25‑6; Whitney, History of Utah, 4:144; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,”

typescript, BYU, 58

Friday, July 10,

1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

It had

rained all night and continued to rain during the day, causing many in the camp

to stay in their tents all day. Captain

James Allen and Indian Agent Robert B. Mitchell issued a proclamation granting

permission to the Mormons to reside on Pottawatomie lands. This was an important point, requested by

Brigham Young during the negotiations to raise the battalion. The proclamation acknowledged that many of

the men would have to leave their families behind, which necessitated this

action.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, in Iowa:

Brigham

Young and company arose early, broke camp by 4:30 a.m., and rode a half mile to have breakfast with

Samuel and Daniel Russell. President

Young’s company continued on until a little after 9 a.m. when they rested their

teams during a thunder shower. At about

1 p.m., they halted their journey when some Fox Indians met then and asked the

“Mormon Chiefs” to wait until they could send for their chief who had something

to say to them. They agreed to delay

their trip ‑‑ it was raining very heavily anyway.

The chief,

named Powsheek, arrived at 7 p.m. He

wanted to see the “Mormon chief,” to learn where the Mormons came from and

where they were going. Powsheek stated

that his people were going off with the Pottawatomies who had recently sold

their land to the government. He was

interested in traveling with the Mormons as they traveled to their new tribal

lands.

James S.

Brown continued his trek to join the battalion. “We journeyed, much of the time in heavy rain and deep mud,

sleeping on the wet ground without blankets or other kind of bedding, and

living on elm bark and occasionally a very small ration of buttermilk handed to

us by humane sisters as we passed their tents.”

Near Fort Laramie,

Wyoming:

The

“Mississippi Company” of Saints, consisting of about fourteen families, decided

to leave the Oregon Trail and head south to spend the winter on the Arkansas

River at what would later be called Pueblo, Colorado. They had met a man named John Richards, who had a fur trading

post at Fort Bernard, about eight miles east of Fort Laramie. Richards told them that Mormons were going

up the South Fork of the Platte. When the Mississippi Company learned this

news, they held a council and decided not to head farther west, but to find a

place to spend the winter on the east side of the mountains. Richards told them that the head of the

Arkansas River was the best place, where corn was growing, and settlements were

nearby where they could get supplies.

He was on the way to take buffalo robes to Taos [New Mexico] from his

trading post and offered to be their guide.

The Saints decided to follow Richards to Pueblo.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

Daniel

Bailey, age forty-two, died. He was the

husband of Sarah Currier Bailey.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 227‑28; Brown, Life of a Pioneer,

26; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

176; Journal History; “John Brown Journal,” Our Pioneer Heritage,

Vol. 2, p.428; Black, Membership of

the Church 1830‑1848

Saturday, July 11, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Wilford

Woodruff went to visit Thomas L. Kane, who had also recently arrived at Council

Bluffs. Colonel Kane informed him that President Polk was

very favorable toward the Mormons.

Elder Woodruff wrote, “Col Kane manifested the spirit of a gentleman and

much interest in our welfare. From the

information we received from him, we were convinced that God had began to move

upon the heart of the President and others in this nation to begin to act for

our interest and the general good of Zion.”

Hosea Stout also met Kane. He

wrote of him, “he was quite an intelligent man notwithstanding he was

uncommonly small and feminine.” John

Taylor wrote, “We had some conversation with him [Kane] during which he

manifested a spirit of sympathy for us.”

After

meeting with the brethren, Col. Kane wrote a letter to George Bancroft, the

secretary of the navy. Col. Kane had

intended to travel with Mormons to California during this season but he wrote,

“Every day, too, renders it more vain for the [Mormon] people to attempt

proceeding to California this season, and I have been acquainted confidentially

by those in authority, that such has ceased to be their intention.” Thus he informed Bancroft that he would not

be traveling to California during this year.

Phinehas

Richards’ company arrived at the Council Bluffs area and set up camp near John

Van Cott’s tent. Mary Richards felt

very weary after the long journey from Mount Pisgah.

Between Mount

Pisgah and Council Bluffs, in Iowa:

Brigham

Young again met with the Indian Chief Powsheek. He authorized Cyrus H. Wheelock to give a two‑year‑old

heifer to the Indians. Powsheek was

still interested in locating his tribe near the Mormons. President Young told him that after they

settled over the mountains that they would send men to hunt for them in return

for blankets, guns and other goods.

Powsheek spoke of Joseph Smith and his murder. He had been acquainted with the Prophet and knew that he was a

great and good man.

At 8:10

a.m., Brigham Young and his company started their journey again. At 10:22 a.m., they stopped at the west

branch of the Nodaway to visit with Ezra Chase. They continued on at 11:30 a.m. and arrived at Pottawatomie

Indian Village at 1:45 p.m. An Indian

presented to them two sheets of hieroglyphics from the Book of Abraham and also

a letter from their father, “Joseph” dated 1843. The company continued on and arrived at the Nishnabotna at 8 p.m.

where they camped for the night.

Brigham Young tried to sleep in his carriage but the mosquitoes were bad

and he only had a little rest.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

A few

Mormons left Nauvoo and traveled about twelve miles, near Pontoosuc to harvest

a field of grain with some of the new non‑Mormon citizens. As they were working, at 9 a.m., a company of about twelve men was seen on

the north side of the field. Another

company of 50‑60 was on the west and a third company on the east. They were trapped. The workers sent one of their men, James Huntsman, with a white

handkerchief to meet them. He asked the

mob leader what they wanted. “You shall

soon know!” The workers were surrounded and their guns were taken from

them. One member of the mob threatened

to blow out the brains of Archibald Newell Hill if he did not give up his gun.

The mob

took the men to the house and after getting some hickory switches, they took

each man, two at a time to the field and gave them each twenty lashes. Archibald Hill’s brother, John, recorded, “I

was taken out, placed in the ditch on my knees with my breast on the bank, and

a man wielded a large hickory switch with both his hands across my shoulders

striking me twenty‑one times, which disabled me from doing the least

service for myself for about a week.”

The mob then smashed several of their guns and stole the others. The men were ordered to go back to Nauvoo

and not to look back. After they had

gone fifty yards, a gun went off and a ball “whizzed” close to John Hill’s

head.

When word

of this outrage was received back at Nauvoo, a handbill was issued calling for

the arrest of the men who beat the Hills.

A company of sixty men was organized.

They left Nauvoo at 10 p.m., and proceeded to the mob leader’s house,

John McAuley (or M’Calla). They

succeeded in arresting him late at night.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 228‑32; Rich, Ensign to the Nations,

39; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:58; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 177; “John Taylor’s

Journal”; “The Historians Corner,” BYU Studies, 18:1:127; “Lyman

Littlefield Reminiscences (1888),” 167‑68; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters,

69

Sunday, July 12, 1846

Council Bluffs, in Iowa:

Brigham

Young and his traveling companions broke camp at 4 a.m., rode for a few miles,

and ate breakfast with Pleasant Ewell. They then continued on and visited the

various camps along the way, passing 30‑40 companies. They finally arrived at Council Bluffs and

stopped at Elder John Taylor’s camp on the bluff, which was about sixty feet

west of the lower bridge on Mosquito Creek.

Wilford Woodruff was camping near this bridge. Elder Parley P. Pratt was

camping about 160 feet to the north.

A meeting

was held at 5:30 p.m. in a large bowery which had been recently put up between

Elder Taylor’s tent and Elder Woodruff’s tent.

Before the meeting, a “Liberty Pole” was raised nearby by William J.

Johnston and Samuel H. Rogers. It consisted of a white sheet with an

American flag underneath. The pole

would be a rallying point for raising the Battalion.

At the

meeting, Elder Woodruff spoke for an hour, telling about his mission to

England. Mary Richards wrote to her

husband, Samuel W. Richards who was on his way to England, “[Elder Woodruff]

spoke of the prosperity of the Church there, said if 50 good Elders would go

there who would know or teach nothing [but] Christ and him Crucified for was

all they had aught to teach that they would find plenty to do & their

labors would be blest with success.”

Elder

Parley P. Pratt next spoke and condemned the common practice of swearing among

the men and boys. He then spoke about

the raising of the battalion, trying to further convince the Saints that it was

the right thing to do. Even Hosea Stout

was feeling better about it. “Indeed it

needed considerable explaining for every one was about as much prejudiced as I

was at first.” John Taylor also spoke

and tried to convince the audience that defeating the Mexicans was in the best

interests of the Church because the Mexican government would only tolerate the

Catholic faith.

At 6 p.m.,

the Council met to write a letter to Orson Pratt, who was across the Missouri

River. They wanted to notify all those

who had already enlisted, to come to the main camp for a meeting in the

morning. All of the other brethren were

notified to attend a meeting at noon.

Pontoosuc,

Illinois:

Phinehas

Young, his son Brigham, Richard Ballanyne, and James Standing arrived at

Pontoosuc at 10 a.m. They were on their

way home to Nauvoo after purchasing flour at McQueen’s Mill in Henderson

County. A Mrs. Hanover came running

toward them, asking if they were Mormons and told them to flee. She said a mob had one of the Mormons, James

Herring, and was swearing that they would cut him to pieces and kill every

Mormon they could find. They had heard

enough, and started to flee as fast as they could. As they approached Appanoose, while watering their horses, ten

armed men came up yelling and screaming, pointing guns, asking if they were

Mormons. Phinehas said they were. The mob demanded that they return to

Pontoosuc. They asked why. The reply was, “because you are

Mormons.” The Mormons questioned the

men’s authority. The mob’s reply was,

“By God gentlemen, these weapons are our authority.” They were taken back to Pontoosuc, where they were met by fifty

armed men, including apostate Francis M. Higbee. Higbee told them that they were being taken hostage for the

safety of McAuley and the others who had been arrested in Nauvoo.

The

brethren were taken to Jeremiah Smith’s store house, near the river, and kept

under a guard until the evening. Then

they were taken in a wagon under heavy guard toward McQueen’s mill. They soon came to a thicket of brush, were

taken through a gate into the woods, and then on to a prairie. Next, they were ordered to get out of the

wagon and form a line. Phinehas Young

asked if they were going to kill them.

The hostages were assured that they would be safe as long as they did

not try to escape and if the prisoners at Nauvoo were freed.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

The Nauvoo

posse brought mob leader, John McAuley to Nauvoo in the morning. Later in the day, the “new citizens”

received a letter from Phinehas Young and others who had been taken hostage by

the mob. They wrote:

The citizens

of Pontoosuc have taken five of us (Mormons) in retaliation for the arrest of

Maj. McAuley and Mr. Brattle and perhaps others, and intend to detain us as

hostages for the safety and release of those gentlemen. They are determined to retaliate for any

outrage or insult that those gentlemen may receive, upon us, we therefore

request that you will immediately release the gentlemen alluded to, so that we

may gain our liberty and safety; you may depend upon this resolution being

carried into effect.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 232‑33, 277‑78; “John Taylor

Journal”; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

177; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:59; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters, 75; Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 1846‑1852,

261

Monday, July 13, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

Heavy rain

showers fell, which lasted until 10 a.m.

Jesse C. Little offered to deliver a letter for Mary Richards to her

husband, Samuel W. Richards, who recently left on his mission to England. Mary wrote in her letter, “I have got up in

the waggon to try to write one but it rains so fast & the wind blows so

hard that I find it almost impossible, the things are piled so high in the

waggon that I cannot sit upright & you can well see that the rain blotches

every mark I try to make.”

At 11

a.m., the battalion recruitment meetings began. Major Jefferson Hunt called out the first company of

volunteers. Brigham Young met with

Thomas L. Kane and mentioned that “the time would come when the Saints would

support the government of the U.S. or it would crumble to atoms.”

Later, at

12:45 p.m., a general meeting for the camp was held. Music was played by the band.

Brigham Young arose and addressed the large assembly under the bowery. He stated that the purpose for the meeting

was to furnish the five hundred volunteers that were needed for the

battalion. He mentioned that many were

worried about leaving their families behind, but he said, “My experience has

taught me that it is best to do the things that are necessary and keep my mind

exercised in relation to the future. . . . The blessings we are looking forward

to receive will be attained through sacrifice.

We want to raise volunteers.”

He

mentioned that many felt that he did not understand their unique

circumstances. He replied that there

was not time to reason with them. “We

want to conform to the requisition made upon us, and we will do nothing else,

till we have accomplished this thing.

If we want the privilege of going where we can worship God according to

the dictates of our consciences, we must raise the battalion.” Some feared that they would die, fighting in

battles. He countered the argument by

prophesying, “All the fighting that will be done will be among yourselves, I am

afraid.” He pressed on, stated that

they had enough men in Council Bluffs on this day to raise the five hundred men

needed, they did not even need to wait for the men at Mount Pisgah. After they were finished talking, volunteers

would be called to come forward.

Colonel

Thomas L. Kane arose and apologized for being too sick to speak, but he

endorsed the words of President Young.

Elder Orson Hyde next spoke and called, “Arise, then, the standard is

raised, the call is made. Shall it be

in vain, NO! Let us rally to the standard and our children will reverence our

names; it will inspire in them gratitude which will last for ever and ever!”

Brigham

Young again spoke and mentioned that they had been fleeing from the “old

settlers” of various places for years.

Well, they now had the chance to be the “old settlers” themselves in the

west. “If any man comes and says get

out, we will say, get out.” He closed

by promising the men that their families left behind would be taken care of.

The men

voted that Brigham Young and the council should nominate the officers for the

battalion. Captain Allen, of the U.S.

Army, spoke and expressed his impatience, that time was wasting away. The battalion must be raised now. Any time wasted would have to be made up on

the road. Captain Allen spoke of

clothing that would be needed included some warm wool clothing. Merchandise would be available to purchase

at Fort Leavenworth at reasonable prices.

Brigham Young again spoke up and said, “Those who go on this expedition

will never be sorry, but glad to all eternity; but those who are not here to go

will be sorry.”

At 5 p.m.

the council met together to nominate officers.

Before the day was through, three and a half companies of at least

seventy men each were organized. The

captains named were Jefferson Hunt, Jesse D. Hunter, James Brown and Nelson

Higgins.

Hosea

Stout spoke for a time with George A. Smith.

Brother Smith explained how Jesse C. Little and Thomas L. Kane had

worked with the government to bring about the battalion. Brother Stout was finally convinced, “This made

the matter plain and I was well satisfied for I found that there was no trick

in it.”

At 6 p.m.,

a large party was held under the bowery with dancing to the music of the band

until dusk. William Clayton played with

the band. He was distressed because he

watched all of his teamsters enlist in the battalion. He reflected on his sad circumstances. He still had four yoke of oxen missing. His children were sick and he was being asked to look after

Edward Martin’s family while he was away with the battalion. He wrote, “on the whole, my situation is

rather gloomy.”

Mary

Richards was invited to attend the dance.

She later wrote about the dance to her husband, Samuel W. Richards. “Brother Brigham came & introduced Bro

Little to me & desired me to dance with him. I did so . . . this is the first time I have danced since I

danced with my Samuel in the House of the Lord.”

In the

evening, Elder Orson Hyde spoke at length on the law of adoption, which was the

practice at that time to seal people to some of the leaders of the church. This doctrine was new to many at the

meeting. Elder Hyde desired that “all

who felt willing to do so, to give him a pledge to come into his kingdom when

the ordinance could be attended to.”

Luther

Terry Tuttle and Abigail Haws were married on this day at Council Bluffs.

Nauvoo, Illinois:

The

arrested mob leaders were examined before the authorities in Nauvoo. There was great tension in the city. The new citizens again called for help from

the Mormons to organize for the defense of the city.

News had

been received in Nauvoo about the raising of the battalion and the teams which

were on the way back for the poor. The

saints were “greatly cheered” by the proposals made to move the poor out.

Near Nauvoo,

Illinois:

Phinehas

Young and the other hostages were moved the next morning when an alarm was

given that a posse of Mormons was in pursuit of them. It was determined that the hostages should be shot. Phinehas reasoned with the wicked men that

if they did shoot them, the noise would bring the whole Mormon force down on

them. The leader, “Old Whimp” was

convinced and decided to move them, but if they made a noise, or tried to get

away, he would kill them. They were

taken to the thickest part of the forest and led through thickets and swamps,

arriving at William Logan’s home after a journey of about twelve miles. They had been driven like wild beasts at the

point of a bayonet. Brother Ballantyne

was quite sick. They were fed some corn

and bacon, then taken to the woods and forced to march two more miles. They were then lined up and “Old Whimp” and

the others loaded their guns and cocked them.

As Phinehas was protesting, Mr. Logan rode up and warned them that the

Mormons were within a half mile. The

guards shouldered their guns and forced the men to march again to another spot

where they were made to lay still for the night.

Pontoosuc,

Illinois:

Brother

William Anderson was appointed deputy sheriff to raise a posse of 50 men to go

in search of the hostages. They

traveled through the night and arrived at Pontoosuc at daybreak. They discovered that a large company of men

was in the brush just outside the town.

The posse searched the brush on both sides of the road and soon found

them. Many of them had their rifles

cocked and were taking aim. They were

led by apostates Francis and Chauncey Higbee.

The mob numbered about three hundred men.

William

Anderson called out to the mob:

O, yes we

know you are there, and we know how many you number. If there were five times as many there we should not be afraid of

you. There are only 50 of us here but

there are five hundred a little way back.

We have the authority and hold the powers to search the town for our

brethren. If any one of you snaps a cap

we will lay your town in ashes. We

command you in the name of Sheriff Backenstos whose servants we are, to come

out of the bushes and lay down your arms.

The men came out and gave up their arms. The posse took the Higbees and others

prisoner and then searched the town for the hostages but could not find them.

Sources:

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 233‑38, 278‑79, 329; Brooks, ed., On

the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 178; William

Clayton’s Journal, 54; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters, 78; “George Morris Autobiography,”

typescript, BYU; LDS Biographical Encyclopedia. Jenson, Andrew, 3:729

Tuesday,

July 14, 1846

Council Bluffs, in

Iowa:

At 9 a.m.,

the first Mormon Battalion company (Company A) with Jefferson Hunt as the

captain, started to make out their muster roll. Another general meeting was held, calling for more volunteers. Heber C. Kimball addressed the gathering and

said the opportunity for raising the Mormon Battalion should be “acknowledged

to be one of the greatest blessings that the great God of heaven ever did

bestow upon this people.” By 10:30, the

fourth company was filled up and marched out under the direction of Orson Pratt. The Council met together to select the

officers in that company.

Many of

the young men desired to enlist.

Eighteen-year-old Aroet Hale wrote:

I had a

desire to go with the battalion as a drummer boy, being a member of the martial

band in Nauvoo. . . . President Heber C. Kimball talked to me. Said he, “Aroet, you have been away from

your father and mother five months in the camp of Israel, as a teamster. Your dear father is on crutches with a

broken leg and no help but your mother and her little ones.” I took President

Kimball’s counsel and well that I did.

It was

about this day that Colonel Thomas L. Kane, still recovering from his illness,

was taking a walk through the woods near the camp with Henry G. Boyle. They passed by a man praying in secret hear

the edge of the woods. Brother Boyle

wrote: “It seemed to affect [Kane]

deeply, and as we walked away he observed that our people were a praying

people, and that was evidence enough to him that we were sincere and honest in

our faith.” As they walked on, they

walked near yet another man beginning to pray.

Boyle wrote:

We had

involuntarily taken off our hats as though we were in a sacred presence. I never can forget my feelings on that

occasion. Neither can I describe them,

and yet the Colonel was more deeply affected that I was. As he stood there I could see the tears

falling fast from his face, while his bosom swelled with the fullness of his

emotions. And for some time after the

man had arisen from his knees and walked away towards his encampment, the

Colonel sobbed like a child and could not trust himself to utter a word.

Hosea

Stout had a long interview with Brigham Young, seeking his counsel and

desires. Brother Stout recounted his

days of suffering as he tried to carry out Brigham Young’s order to bring the

public arms to Council Bluffs. Brigham

Young told him that he wanted him to continue to work for the Church in a

military role. After the battalion

left, he wanted to organize a military organization that Brother Stout would be

involved in. He asked Brother Stout to

not say anything about it before the battalion left, because it would only