Thursday, July 1, 1847

On the Green River,

Wyoming:

The

pioneers started to cross over the Green River. One of the rafts did not work very well because the logs were

waterlogged. They went to work, to

construct another raft. The wind blew

hard, causing the work to be stopped in the afternoon, and only fourteen wagons

were brought across. They tried to swim

the cattle across, but had great difficulty.

The second raft was completed by the evening.

More of

the pioneers came down with Mountain Fever, including Clara Decker Young, John

Greene, William Clayton, Ezra T.

Benson, George A. Smith, George Wardell, and Norton Jacob. Those who had been sick the day before were

much better, so it appeared that the violent pain and fever usually only lasted

for a day. So far, about twenty of the

pioneers had taken ill with the mysterious illness.

Samuel

Brannan continued efforts to convince the brethren that California was the land

of Zion for the Saints. He told them

that John Sutter, of Sutter’s Fort, wished to have the Saints settle near him

in the Sacramento region. Brother

Brannan tried to paint a bleak picture of the Rocky Mountain region by saying

that he saw more timber on the Green River where they now were than anywhere on

his route since he left California.

Joseph

Hancock killed an antelope.

The Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The

ferrymen crossed across fifty‑six wagons for three emigration companies

and performed $12.85 worth of blacksmithing.

Appleton Harmon wrote: “We were

all very tired and wanted rest.” They

learned that one company with thirty‑five wagons went up the river and

crossed over using one of the rafts that the pioneers had built.

On the Loup Fork,

Nebraska:

The

morning was cold and windy as the second pioneer company worked to cross over

the more than five hundred wagons. The

river was about a half mile wide and shallow, but the bottoms were full of

quicksand. Perrigrine Sessions

wrote: “[We] had to drive all our

cattle several times across to tamp the quicksand so that we could cross our

wagons.” They had to double the teams

on the wagons. They traveled away from

the river, head back to the Platte.

John Taylor’s company went eight miles and Jedediah M. Grant’s company

camped three miles behind. A few

buffalo were spotted for the first time during the day. Isaac C. Haight wrote: “So we pass over rivers, hills and plains as

though all was a smooth plain.”

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

A son, Don

Carlos Johnson, was born to Aaron and Jane Scott Johnson.

Sources:

“Jesse W. Crosby

Journal,” typescript, BYU, 34; Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury, 117; The

Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 182; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 14:163; “Albert P. Rockwood Journal,” typescript,

BYU, 60; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:222; Bagley, ed., The

Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 216; “Isaac C. Haight Journal,” typescript, 41

Friday, July 2, 1847

On the Green River,

Wyoming:

Forty‑seven

wagons crossed over the river during the day.

The horse and cattle were taken over the river during the morning with

some difficulty. The day was very hot

and the mosquitoes continued to be terrible.

Several trout were caught near the ferry. One weighed more than seven pounds. Thomas Bullock saw a heap of nine buffalo skulls in one place.

The Twelve

and others met in council at a nearby grove and decided to send three or four

men back to pilot the next pioneer company along their way. Each of the brethren wrote down their views

regarding what counsel should be given to the second pioneer group. Samuel Brannan continued to promote

California as the promised land. He

said that the oats grew wild and did not need to be cultivated. Clovers grew as high as a horse’s

belly. Salmon in the San Joaquin River

were 10‑12 pounds.

Independence Rock,

Wyoming:

Captain James

Brown’s detachments of the Mormon Battalion and Mississippi Saints probably

camped at Independence Rock on this day.

Abner Blackburn noted that the rock was “a huge mass of granite which

covers several acres of ground with hundreds of names marked on its huge

sides.”

Between Loup Fork

and the Platte River, Nebraska:

The

Perrigrine Sessions company traveled twenty miles during the day and camped

without wood and water. A storm blew

through, dropping some much needed rain water, but it also brought wind that

beat against the wagons with force.

Eliza R. Snow wrote: “The

prairie very rolling we only ascend one ridge to come in sight of another, till

about 2 o’clock when our gradual descent gave us a view of the tops of trees

which skirt the river before us.” The

companies traveled six abreast during a portion of the day. A cannon being drawn by the Edward Hunter

company was found by Charles C. Rich abandoned on the trail with the wagon

carriage broken and the tongue gone.

The wagon was repaired and the cannon was brought along. A thunder shower rolled in during the late

afternoon.

Sources:

Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering

the West, 90; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:222;

Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 216‑17; Smart, ed., Mormon

Midwife, 89; The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 182; Bagley,

ed., Frontiersman: Abner Blackburn’s Narrative, 60

Saturday, July 3, 1847

On the Green River,

Wyoming:

A storm

delayed the rafting over of wagons, but by the late afternoon, all of the

wagons were safely across. One of the

rafts was hauled up the east side of the river and stowed for the next pioneer

company to use. The pioneers resumed

their journey in the afternoon, traveled three miles and camped on the Green

River. The grass was good, but there

were dense swarms of mosquitoes making it miserable. Most of the camp was recovering from the strange bout of mountain

fever that struck almost half of the company.

A guide board was put up a mile from Green River that stated it was 340

miles from Fort Laramie.

Norton

Jacob recorded: “After arriving in

camp, Bro. Heber came to visit me and advised me to be baptised. So I went down to the water and Charles

Harper baptised me for the restoration of my health which was confirmed upon me

by Brethren Kimball, Doct. Richards, Markum Barney and Charles [Harper]. The administration had the desired effect

and broke my fever.”

A meeting

was held in the evening and volunteers were asked to go back, meet the second

pioneer company, and to act as guides.

Preference was given to those who had families in the next company. Those who volunteered were: Phinehas H.

Young, Aaron Farr, Eric Glines, Rodney Badger, and George Woodward. Brigham Young stated that he wished that a dozen men would have

volunteered. Since there were not

enough spare horses for each of them, they were given the “Revenue Cutter” wagon

to carry their provisions. They started

to make preparations to return. President

Young announced he would travel with these five men in the morning back to the

Green River, but he wanted the company to hold a Sabbath meeting in the

morning. “I want to have you pray a

little and talk a little and sing a little and have a good long meeting, all

except those who guard the teams, I want them to mind their work.”

On the Sweetwater,

Wyoming:

Captain

James Brown’s detachments of the Mormon Battalion and Mississippi Saints passed

by Devil’s Gate and camped along the Sweetwater. Abner Blackburn wrote that some of the men were afraid to go

through Devil’s Gate “for fear they might land in the bad place.” Like the pioneers before them, they traveled

around the gate and over a ridge.

Brother Blackburn wrote that they came “into a most beautyful valley

carpeted with green grass and herds of buffalo and a few elk and some deer

grazing on its rich meadows.” He

marveled at the mountain of granite that ran parallel with the river without

vegetation, and remarked “The like I never seen before. They must have run short of material when it

was contracted for.”

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

Jim

Bridger arrived at the Mormon Ferry at 11 a.m., and presented to Thomas Grover

a letter of introduction from Brigham Young (see June 29, 1847). With him, were four more Mormon Battalion

soldiers who were on furlough and were returning to Council Bluffs. A company of eight bringing mail from Oregon

arrived near sundown with pack horses and mules. They had been traveling from Oregon since May 5. A letter was sent with Jim Bridger to be

take to Fort Laramie for the next pioneer company notifying them that the ferry

was going to be kept in operation until they arrived.

Between Loup Fork

and the Platte River, Nebraska:

The second

company of pioneers again rejoined the trail created by Brigham Young’s company

and camped on a stream within view of the Platte River. They traveled about fourteen miles. Brother Russell found a bucket near the

trail that he had given to Heber C. Kimball.

Martin Dewitt, of the Perrigrine Sessions company, broke his arm during the

night, while wrestling. Patty Sessions

took out her stove and burned old Indian wickiups in it. Antelope was spotted by some men for the

first time.

Summer Quarters,

Nebraska:

Seventy‑three-year‑old

Sarah Lytle, Nancy Lee, Mary Lane,

Julia Woolsey, and some children started out to Winter Quarters with

Allanson Allen. Along the way, the

wagon tipped over into Mire Creek.

Sarah Lytle was terribly injured.

Her hips were disjointed and her bowles bruised. The others did not receive any

injuries. Samuel Gully, returning from

Winter Quarters, delivering the news of the accident to John D. Lee, who

immediately sent another wagon and team to bring the sisters and children back

to camp.

Council Bluffs,

Iowa:

Roswell

Stevens, age seventy-five, died.

Sources:

Cook, Joseph C.

Kingsbury, 118‑19; The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow,

182; Bagley, ed., Frontiersman: Abner Blackburn’s Narrative, 60 Journals

of John D. Lee, 184; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 38; Watson,

ed., The Orson Pratt Journals, 437; “Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement

Era 15:248; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:223; Whitney,

History of Utah, 1:318; “Luke S. Johnson Journal,” typescript, BYU, 15;

Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 89; “Norton Jacob Journal,” typescript, 101

Sunday, July 4, 1847

On the Green River,

Wyoming:

Norton

Jacob recognized Independence day in his journal by writing: “This is Uncle Sam’s day of

Independence. Well we are independent

of all the powers of the gentiles, and that’s enough for us.”

Brigham

Young, Heber C. Kimball, Wilford Woodruff, Charles Harper, and others traveled

back to the Green River with the five brethren who were heading back to help

guide the second pioneer company. They

were instructed to choose one of their number to help guide the members of the

battalion.

When they

arrived at the river, they saw thirteen horsemen on the other side with their

baggage and one of the rafts. To the

joy of the brethren, they discovered that the men were members of the Mormon

Battalion from Pueblo, led by Sergeant Thomas S. Williams, who had been sent

ahead by Amasa Lyman. They were

pursuing some thieves who had stolen a dozen horses. The thieves had gone on the Fort Bridger and they hoped to get

the horses back. They said that the

whole detachment of about 140 men (also women and children) was about a seven

days’ journey to the east. One of the

soldiers, William Walker, joined the company of five men hoping to meet his

family in the second pioneer company.

Wilford

Woodruff wrote: “We drew up the raft

& crossed them all over but one who returned with our pilots to meet the

company. When we met it was truly a

harty greeting & shaking of hands.

They accompanied us into camp and all were glad to meet.” The pioneers greeted them with three cheers

and “shanking hands to perfection.”

Next, Brigham Young led another cheer by shouting, “Hosannah! Hosannah!

Give glory to God and the Lamb, Amen.”

All joined in the cheer.

While the

brethren were away at the river, the rest of the pioneers met for a public

worship meeting, in the circle of wagons, under the direction of the bishops in

the camp. One of Robert Crow’s oxen

died during the afternoon from eating poison weeds.

William

Clayton wrote: “On the other side the

river there is a range of singular sandy buttes perfectly destitute of

vegetation, and on the sides can be seen from here, two caves which are

probably inhabited by wild bears. The

view is pleasant and interesting.”

The men

from the battalion spent the night with the camp. Several traders passed by the camp at dusk. The Twelve met together to read letters from

Amasa Lyman and Captain James Brown.

These letters were delivered by the advance guard of the battalion. Counsel was given to Samuel Brannan

regarding the Saints in California.

Wilford

Woodruff concluded the day by writing in his journal: “But I must stop writing.

The musketoes have filled my carriage like a cloud and have fallen upon

me as though they intend to devour me.

I never saw that insect more troublesome than in certain places in this

country.”

On the Sweetwater,

Wyoming:

Abner

Blackburn, of the battalion wrote:

“There was a couple of young folks

in the company spooning and licking each other ever since we started on the

road. The whole company were tired of

it and they were persuaded to marry now and have done with it and not wait

until their journeys end.” In the

evening, a wedding was held, complete with a wedding feast afterwards followed

by a dance or ho‑down. “The banjo

and the violin made us forget the hardships of the plains.”

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The

ferrymen sent back letters with Marcus Eastman, a battalion member heading back

to Council Bluffs. He and three other

battalion members were traveling with Jim Bridger. Francis M. Pomeroy bought a horse from the company for

twenty-five dollars.

Between Loup Fork

and the Platte River, Nebraska:

It rained

for a while in the morning. After it

cleared, Patty Sessions took some of the things out of her wagon and discovered

that they were becoming damp in the wagon.

The second company of pioneers held a celebration to recognize

independence day. Parley P. Pratt, John

Taylor, and John Smith addressed the Saints in a public meeting. The leaders asked the pioneers to work together

and to be obedient. They exhorted the

Saints against being “cold and careless and neglecting to pray.” They were cautioned to never take the name

of the Lord in vain. They were warned

to not build large campfires that would attract the Pawnee Indians. It was decided that the companies would

travel separately, because it was just impossible to feed and water so many

people and animals in one place. They

would begin establishing their camps more spread out.

Summer Quarters,

Nebraska:

John Lytle

arrived from Winter Quarters and found his mother critically ill from the

results of her injuries the day before.

At noon, a public meeting was held at John D. Lee’s house. He spoke to them about their

responsibilities as Saints. Other

speakers were Joseph Busby, Brother Baird, Samuel Gully, and Absalom P.

Free. Brother John H. Redd was troubled

in his mind about going to the west. A

storm blew in and it rained during the late afternoon. A steam boat was spotted in the river, late

in the evening.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

A public

meeting was held. Isaac Morley and

William W. Major spoke to the congregation.

Rain fell in torrents during the afternoon.

Kearny detachment

of the battalion, in Nevada:

The Kearny

detachment of the Mormon Battalion continued traveling along the Humboldt River

toward Fort Hall. One of the men became

sick and had to be left behind, but caught up with the company in the evening.

During

their march across Nevada, battalion member Amos Cox got into trouble with

General Kearny. Private Cox was

guarding a water hole to see that no animals watered until all the men had. Sylvester Hulet recorded: “Gen. Kearny rode his horse up and started

to water it. Uncle Amos [Cox] pulled

his gun and threatened to shoot him unless he took the horse away until all the

men had all drunk and filled their canteens.

Gen. Kearny then departed but afterwards he had Uncle Amos court

martialed and strung up by the thumbs for pulling a gun on his superior

officer.”

Mormon Battalion,

at Los Angeles, California:

Independence

Day was celebrated by the troops in Pueblo de Los Angeles. All of the soldiers were paraded within the

fort at sunrise. The New York band

played the “Star Spangled Banner” while the flag was being raised. Afterwards, nine cheers were shouted by all

the soldiers. “Hail Columbia” was

played and then a thirteen-gun salute was fired by the 1st Dragoons. The companies were then marched back to

their quarters and again returned at 11 a.m.

They paraded some more, this time before Indians and Mexicans. Lt. Stoneman of the 1st Dragoons read the

Declaration of Independence. Colonel

Stevenson spoke and named the fort, “Fort Moore.” The band played “Yankee Doodle,” followed by

a patriotic song presented by Levi Hancock, of the battalion. Colonel Stevenson offered to have the

Declaration of Independence read to the Mexicans in Spanish, but they declined

the invitation.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, at San Diego, California:

Independence

Day was also celebrated by the Mormon Battalion at San Diego. Five large guns were fired at sunrise from

the fort. The battalion members marched

down into the town and gave their officers a salute with their guns. The whole city participated in the

celebration. Captain Jesse Hunter and

Sergeant William Hyde returned from Los Angeles with orders for Company B to

march to Los Angeles, and to leave on July 9.

Some of the leading citizens expressed a strong desire for the battalion

to stay, but most of the men were still very anxious to be discharged. Captain Hunter was disappointed that he had

not been able to raise enough men at Los Angeles to make out a large enough

company to reenlist under his command.

Robert S. Bliss recorded in his journal:

A few days

more & we shall go

To see our

Wives & Children too

And friends

so dear we’ve left below

To save the

Church from Overthrow.

Our absence

from them has been long

But Oh the

time will soon be gone

When we

shall meet once more on Earth

And praise

the God that gave us Birth.

Lockport, New York:

Elder

Lyman O. Littlefield went to find his Uncle Lyman Littlefield’s house near the

Erie Canal. He wrote:

I knocked

at my uncle’s abode and a hospitable voice bid me enter. Being seated, the scene presented within the

compass of that room, to me was of vast moment. I knew that venerable head was my uncle, that the matron at his

side was my aunt, and the young men and the one young lady at the table I felt

sure were my cousins! This was an auspicious moment, to occur on the

anniversary of our nation’s independence! The memories of childhood were

instantaneous in crowding among the most sacred recesses of recollection! My

uncle so much resembled my father! I could not wait longer for recognition! The

following conversation ensued: “Myself ‑‑

’Is your name Littlefield?’ Uncle ‑‑ ’Yes, sir.’ Myself ‑‑

’Have you relatives in the west?’ Uncle‑‑’I suppose I have a

brother somewhere in the western country.

He went away with the Mormons and I have not heard much about him for

twenty years.’ Myself ‑‑ ’What was his given name?’ Uncle ‑‑

’Waldo.’ Myself‑‑’I am well acquainted with a man out there by that

name.’ Uncle ‑‑’That must be my brother. How long have you known him?’ Myself ‑‑ ’My earliest

remembrances are of him and my mother.’ Uncle ‑‑ ’You are not his

son!’ Myself‑ ‑’I am his second son, Lyman, and was named after my

uncle, in whose habitation, and in the midst of these, my cousins, this is a

happy moment!’” “As I entered, the family was partaking of an early supper. I had not seen them since a little boy, some

twenty years previous to that meeting.

To be thus ushered into their presence filled me with emotions of

pleasure. Their joy was exhibited as if

by an electric wave. Simultaneously,

uncle, aunt and cousins sprang from the table to salute me with eager and

hurried words of welcome.

Sources:

Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:223; “Luke S. Johnson’s Journal,” typescript, BYU,

15; “Charles Harper Diary,” 29; Autobiography of John Brown, 77; Watson,

ed., Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 563; Watson, ed., The Orson

Pratt Journals, 437‑38; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 39;

Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering the West, 91; Kelly, ed., Journals of

John D. Lee, 185; Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury, 119; Smart, ed., Mormon

Midwife, 90; Bagley, ed., Frontiersman: Abner Blackburn’s Narrative,

60‑1; Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 218‑19;

“The Journal of Nathaniel V. Jones,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:20;

Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

233‑34; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” Utah Historical Quarterly,

4:110; “Journal Extracts of Henry W. Bigler,” Utah Historical Quarterly,

5:61; “Private Journal of Thomas Dunn,” typescript, 26; William Clayton’s Journal,

282; “Lyman Littlefield Reminiscences (1888),” 193‑95; Bigler, The

Gold Discovery Journal of Azariah Smith, 88; Ricketts, The Mormon

Battalion, 165; “Norton Jacob Journal,” typescript, 101; Schindler, Crossing

the Plains, 219

Monday, July 5, 1847

On the road to Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

At 8 a.m.,

the pioneers continued on their journey despite the fact that many of the

brethren were still sick with the mountain fever. Orson Pratt speculated that the fever could be caused “by the

suffocating clouds of dust which rise from the sandy road, and envelope the

whole camp when in motion, and also by the sudden changes of temperature; for

during the day it is exceedingly warm, while snowy mountains which surround us

on all sides, render the air cold and uncomfortable during the absence of the

sun.”

They

followed the Green River for three and a half miles. After resting the animals, they continued on the road which

headed west away from the river. They

climbed some bluffs and then traveled over rolling hills. At 4:45, after a total of twenty miles, they

arrived at Ham’s Fork, a swift stream about 70 feet wide. The prickly pear cacti were in bloom, some

with yellow flowers, others with red.

Rain fell in the evening, but the storms seemed to stay close to the

mountains.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The

Wallace Company (Abraham Smoot Hundred) had a wagon break down while crossing

Wood River. This delay caused them to

camp several miles behind the main camp.

The rest of the camp reached Grand Island and discovered a guide board

left by the first pioneer company that read:

“April 29th, 30th, 1847.

Pioneers all well, short grass, rushes plenty, fine weather, watch

Indians ‑‑ 217 miles from Winter Quarters.” Jesse Crosby wrote:

The whole

camp of near 600 wagons arranged in order on a fine plain, beautifully adorned

with roses. The plant called the

prickly pear, grows spontaneously; our cattle are seen in herds in the

distance; the whole scene is grand and delightful. Good health and good spirits prevail in the camp. Our labors are more than they otherwise

would be, on account of the scarcity of men ‑‑ 500 being in the

army, and about 200 pioneers ahead of us.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

The guard

met to settle up with Daniel Russell, a member of the High Council who had ten

of his cattle found in the corn field.

By the city law, he was supposed to pay a fine of ten dollars. He had appealed to the Council and they told

him to settle the matter with the guard.

Hosea Stout wrote, “So we left it to his own conscience &

magnanimity to say what was just as he was one of the council and helped make

the law.” He decided to pay ten bushels

of corn and ten bushels of buck wheat.

The guard accepted this payment.

Brigham

Young’s sister, Fanny Young Murray, wrote a letter to Gould and Laura Murray of Rochester, New York:

Brigham and

Heber with nearly two hundred of chosen men, left this place on the 14th of

April for the Rocky Mountains. We heard

from them by way of the far company, when they were fifty miles from this

place, since which, we have heard nothing, nor do we expect to until we see

them, and that may be a long time, or it may be this fall. They will probably go till they find a place

where we can rest for a little season.

She wrote

about the troubles with the Omaha Indians:

We do not

suffer anything from fear of the Indians, for we know that for their sakes we

are suffering all these things, and we are sure that the Lord our God will not

suffer them to destroy us. There has

been great destruction of life, both with man and beast, since we left Nauvoo,

but none of these things move us while we are keeping the commandments of our

Lord and Master, for we know that whether we live or die, we are His.

Fanny

wrote about Winter Quarters and the Mississippi River:

There have

been but two steamboats here this season; this makes the river appear rather

lonely, except when the fur boats are scudding down; seven were seen at once,

yesterday; we hailed them with joy -- I mean with our eyes, for it looks so

lonely to see no raft upon the water. . . . I should like to tell you how many

hundred houses we have built, but have not lately ascertained. In March there were about eight hundred, and

many have been built since. Some are

very good log houses, and others about the medium, and many poor indeed, but

better than none. The land is far from

being level here, but the hills are really beautiful -- far more so, to me,

than level land could be. If you could

sail up the river and take a peep at our town, you would say it was romantic

and even grand, notwithstanding the log huts.

Sources:

Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering

the West, 91; Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury, 119; Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 438‑39; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s

Journal, 3:224; Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 219;

Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, 1:265; The Personal Writings of

Eliza Roxcy Snow, 182; “Jesse W. Crosby Journal,” typescript, BYU, 24‑5;

Woman’s Exponent, 14:11:82

Tuesday, July 6, 1847

On the road to Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

After

traveling 3 3/4 miles, the pioneers forded Ham’s Fork at a point where it was

about forty feet wide and two feet deep.

In 1 1/ 2 miles, they came to Black’s Fork and crossed it.

Wilford

Woodruff recorded: “Man & beast,

Harnesses & waggons, were all covered with dust. . . . The face of the

country is the same to day as usual Barren, Sand & Sage, with occasionally

A sprinkling of flowers some vary beutiful.”

In

thirteen more miles, they recrossed Black’s Fork and camped on the bank. The grass was good and there were many

willow trees near camp. William Clayton

wrote:

At this

place there is a fine specimen of the wild flax which grows all around. It is considered equal to any cultivated,

bears a delicate blue flower. There is

also an abundance of the rich bunch grass in the neighborhood of the river back

and many wild currants. The prairies

are lined with beautiful flowers of various colors ‑‑ chiefly blue,

red and yellow, which have a rich appearance and would serve to adorn and

beautify an eastern flower garden.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The

ferrymen took across an emigrant company with eighteen wagons. Three of the wagons left without paying the

fifty-cent fee. Another company of

twenty‑two wagons went up the river to ford it by raising their wagon

beds. The river had been falling fast,

making this method of crossing possible.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

Across

from Grand Island, a daughter, Sarah Ellen Smithies, was born to James and

Nancy Smithies at 11 a.m. This delayed

the Abraham Smoot Company for a few hours.

Patty Sessions wrote: “Go 18

miles camp on the bank of a stream from the Platte River where the Indians had

camped. We burnt their wickeups for

wood, some waided the river to get wood, brought it over on their backs. The camp did not all get up last night

neither have they to night. Smoots Co

have not been heard from since Monday, Grants Co did not get up to night.” Jedediah M. Grant’s hundred were delayed

because of traffic problems with John Taylor’s company. Abraham Smoot’s company camped at the spot

where some of the companies had rested at noon.

A son,

Benjamin Leavitt Baker, was born to Simon and Charlotte Leavitt Baker.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

Ellen

Aurelia Williams, age six months, died of congestive chills. She was the daughter of Gustavus and Maria

Williams.

Summer Quarters,

Nebraska:

Sarah

Lytle, age Seventy‑three, died of injuries received a few days earlier

from a wagon tipping over. She was

buried under the direction of Joseph Young.

Mormon Battalion,

at Los Angeles, California:

During the

morning, the battalion attended a funeral service for a soldier of the 1st

dragoons who had died during the previous evening. He was buried with the honors of war and interred in a Catholic

Cemetery.

Sources:

Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 439; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:224; Kelly, ed., Journals of John D. Lee, 185‑86; Cook, Joseph

C. Kingsbury, 119; Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 90; The Personal

Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 182‑83; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes

West, 39; William Clayton’s Journal, 283; Tyler, A Concise

History of the Mormon Battalion, 297

Wednesday, July 7, 1847

On the road to Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

The

pioneers restarted their journey at 7:45 and once again crossed Black’s Fork

after traveling about two miles. The

wind blew strongly, making the road dusty and unpleasant for traveling. They rested at noon, on the banks of a swift

stream.

In the

afternoon, they saw a number of Indian lodges on the south side of the

road. These were occupied by trappers

and hunters who had taken Indians as wives.

Children were seen playing around the lodges. Many horses were seen grazing nearby. After crossing four more streams, they arrived at the historic

Fort Bridger.

Howard

Egan described the fort: “Bridger’s

Fort is composed of two log houses, about forty feet long each, and joined by a

pen for horses, about ten feet high, and constructed by placing poles upright

in the ground close together.” Orson

Pratt wrote: “Bridger’s post consists

of two adjoining log‑houses, dirt roofs, and a small picket yard of logs

set in the ground, and about 8 feet high.”

Horace K. Whitney added: “This

is not a regular fort as I at first supposed, but consists of 2 log houses

where the inhabitants live & also do their trading.” The roadometer indicated that Fort Bridger

was 397 miles from Fort Laramie.

They made

their camp about a half mile west of the fort.

Some of the pioneers caught several trout in the brooks. Erastus Snow wrote: “It is about the first pleasant looking spot

I have seen west of the pass. This is

the country of the Snake Indians, some of whom were at the fort. They bear a good reputation among the

mountaineers for honesty and integrity.”

William Clayton had a different view of their location. “The country all around looks bleak and

cold.”

The

advance guard of the battalion found the horse thief at the fort who had helped

to steal ten of their horses. They had

previously recovered eight of the horses and asked about the remaining

two. The thief said they were gone to

Oregon.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

A Captain

Magone’s company of thirty‑six wagons was taken across over the river for

one dollar each. Captain Magone asked

for the names of all the captains of the companies and the number of

wagons. He said he would publish this

information in a history. There was a

Catholic Bishop and seven priests in this company. Eight men from Oregon arrived with pack mules and horses heading

east. They were ferried across and they

hired the men to do some blacksmithing.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The second

pioneer company traveled fifteen miles and found another guide board left by

Brigham Young’s pioneers. It said that

they had killed eleven buffalo. A wagon

ran over one of Perrigrine Sessions’s feet.

His foot hurt so much that he could not drive his team. The companies passed by a large prairie dog

village. Jesse W. Crosby described

these villages: “They are certainly a

curiosity to the traveler; they live in cells, the entrance of which is guarded

against the rain. Thousands of these

little creatures dwell in composts, and as we pass great numbers of them set

themselves up to look at us, they resemble a ground hog, or wood chuck, but

smaller.” Isaac C. Haight added: “Passed several villages inhabited by dogs a

little larger than the squirrel. Some

were killed. They are good to eat.”

Sarah Rich

recorded:

We came to

a land alive with what is called "prairie dogs." They live in holes in the ground, and made

the hills resound with their barking all night long. They are about the size of small puppies, and as cunning as they

can be. They sat near their holes by

hundreds and barked and yelped until the boys got almost up to them, then they

dodged into their holes or dens and stuck their heads out again and

barked. Some of the men shot at them. They were such handsome little dogs with

more fur than hair on them. If we could

have caught them alive, we would have tried to tame them just because they were

so small and pretty.

During the

morning, the Joseph Noble fifty were ordered to leave the “beaten path” and

break a new trail. Eliza R. Snow

wrote: “It made hard riding for me, yet

I felt like submitting to ‘the pow’rs that be’ & endure it altho’ the 2

roads were unoccupied.” Her company

passed by the Charles C. Rich Company who was repairing two wagons.

Summer Quarters,

Nebraska:

Isaac

Morley arrived from Winter Quarters and notified John D. Lee to come to the

city on July 10 to reorganize the Summer Quarters company.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

On this

warm day, Mary Richards took her bed and bedding outside, scaled the bedstead

and the log around her bed, and scrubbed the floor. This treatment was needed because she had been bothered by bed

bugs.

Daniel

Russell, a member of the High Council, went to see Hosea Stout to inform him that

he had consulted with the High Council and it had been decided to disband the

Winter Quarters police guard led by Brother Stout. This was shocking news, and Brother Stout questioned in his mind

if it was true, since Daniel Russell had recent run‑ins with the guard.

St. Louis, Missouri:

A son,

Thomas Brigham Wrigley, was born to Thomas and Grace Wilkinson Wrigley.

Sources:

Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering

the West, 92‑3; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 39‑40;

Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 90; The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy

Snow, 183; “Jesse W. Crosby Journal,” typescript, BYU, 35; Kelly, ed., Journals

of John D. Lee, 186; “Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement Era

15:249; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:224; Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 439‑40; Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the

Saints, 220; William Clayton’s Journal, 285; Brooks, ed., On the

Mormon Frontier, 1:265; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters, 151; “Isaac C.

Haight Journal,” typescript, 42; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,” typescript, BYU,

75‑6

Thursday, July 8, 1847

Fort Bridger,

Wyoming:

The

morning was cold. Ice formed during the

night but melted as soon as the sun rose.

By 9 a.m., the temperature stood at sixty‑six degrees. The pioneers decided to spend the day at

Fort Bridger, preparing for the rugged roads ahead in the mountains. While blacksmith work was being performed on

the wagons and horse shoes, some of the men tried their hand at fishing for

trout. Wilford Woodruff wrote about his

efforts fly fishing:

The man at

the fort said there were but very few trout in the streams, and a good many of

the brethren were already at the creeks with their rods & lines trying

their skill baiting with fresh meat & grass hoppers, but no one seemed to

ketch any. I went & flung my fly

onto the [brook] and it being the first time that I ever tried the artificial

fly in America, or ever saw it tried, I watched it as it floated upon the water

with as much intense interest as Franklin did his kite when he tried to draw

lightning from the skies. And as

Franklin received great joy when he saw electricity or lightning descend on his

kite string, in like manner was I highly gratifiyed when I saw the nimble trout

dart my fly hook himself & run away with the line but I soon worried him

out & drew him to shore.

Within

three hours he had caught twelve large trout.

In the

afternoon, Wilford Woodruff went to Fort Bridger and traded a rifle for four

buffalo robes. The prices were high,

but the robes were of good quality.

Howard Egan traded two rifles for nineteen buckskins, three elkskins,

and some material for making moccasins.

Heber C. Kimball obtained hunting shirts, pants, and twenty skins.

The

brethren decided to head to the southwest toward the Salt Lake. They wrote a letter to Amasa Lyman, with the

battalion detachment, discussing what should be done with the soldiers.

We

understand that the troops have not provisions sufficient to go to the western

coast, and their time of enlistment will expire about the time they get to our

place; they will draw their pay until duly discharged, if they continue to obey

council; and there is no officer short of California, who is authorized to

discharge them; therefore, when you come up with us, Capt. Brown can quarter

his troops in our beautiful city, which we are about to build, either on

parole, detached service, or some other important business, and we can have a

good visit with them, while Capt. Brown with an escort of 15 or 20 mounted men

and Elder Brannan for pilot, may gallop over to the headquarters, get his pay,

rations and discharge and learn the geography of the country. If Captain Brown approves these suggestions

and will signify the same to Brother Brannan, so that he can discharge his men

and remain in camp; otherwise he [Brannan] is anxious to go on his way.

Andrew

Gibbons was tried before

the Twelve for an assault on George Mills.

Both had used abusive language against each other and ended up asking

for forgiveness. Brother Gibbons was

honorably acquitted. The Council also

decided that Sergeant Thomas Williams of the battalion and Samuel Brannan

should head back to meet Captain James Brown’s company of the battalion. William Clayton explained: “Inasmuch as the brethren have not received

their discharge nor their pay from the United States, Brother Brannan goes to

tender his services as pilot to conduct a company of fifteen or twenty to San

Francisco if they feel disposed to go there and try to get their pay.”

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The men

performed $6.40 worth of blacksmithing for emigrant companies and Luke Johnson

cleaned teeth and did other dentistry for $3.00.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The

pioneers found another buffalo skull with a message that Brigham Young’s

company had written to them on May 4.

Perrigrine Sessions wrote that this gave the Saints much joy. Brother Sessions spotted some wild or stray horses. Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor caught the

horses and they were brought into the camp.

The companies crossed several streams and built bridges over a number of

them. Buffalo was spotted for the first

time.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

Before

Hosea Stout notified the guard about the order to disband, he went to see the

president of the High Council, Alpheus Cutler.

Brother Stout could not believe that the order from Daniel Russell to

dissolve the guard was true. President

Cutler told him that there had been discussion on this subject, but no order to

stop the guard has been issued. He told

Brother Stout to keep the guard together and the matter would again be

discussed at the next High Council meeting.

Hosea

Stout wrote:

This was

one of the hottest days I ever saw. But

in the evening the wind came from the North accompanied by torrents of rain

which ran like rivulets down the streets.

It bursted in to my house in torrents and filled it up in a few moments

untill I had to throw the water out by the bucket full untill we were all

completely drenched. This I believe was

the hardest rain this season.

Eliza Jane

Godfrey, age six months, died of diarrhea.

She was the daughter of Joseph and Ann Reeves Godfrey.

Kearny detachment

of the battalion, in Nevada:

The small

detachment of the battalion reached a crossroad in present‑day northeast

Nevada. The road to the right was a two‑day

journey to the Salt Lake. They took the

road to the left which headed to Fort Hall.

They camped at the headwaters for the Humboldt River.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, at San Diego, California:

Henry

Bigler wrote: “Our brick masons

[Philander Colton, Rufus Stoddard, Henry Wilcox, and William Garner] finished

laying up the first brick house in that place and for all I know the first in

California. The building, I believe,

was designed to be used for a courthouse and schoolhouse. The inhabitants came together, set out a

table well spread with wines and different kinds of drinks.”

Sources:

Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 439‑40; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s

Journal, 3:225; “Charles Harper Diary,” 29; Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury,

119; Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 90; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West,

40; Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering the West, 93; “The Journal of

Nathaniel V. Jones,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:21; William

Clayton’s Journal, 286; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, 1:265

Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 221; Journal History,

8 July 1847.

Friday, July 9, 1847

Fort Bridger,

Wyoming:

Samuel

Brannan, Thomas Williams, and possibly a few others returned toward South Pass

to meet the detachment of the Mormon Battalion, taking with them a letter from

the brethren. Most of the advance party

of the battalion remained with the pioneer company, again increasing its

numbers.

At 8 a.m.,

the rest of the pioneers left their camp near Fort Bridger and traveled on

rough roads. Erastus Snow wrote: “We took a blind trail, the general course

of which is a little south of west, leading in the direction of the southern

extremity of the Salt Lake which is the region we wish to explore.” They were barely able to discern the trail

left the previous year by the Donner‑Reed party and others. After six and a half miles, they arrived at

Cottonwood Creek and rested their teams.

During the

warm afternoon, the pioneers ascended a long, steep hill, eight miles from Fort

Bridger. The descent on the other side

was the steepest and most difficult they had yet come across. They passed some large drifts of snows. Thomas Bullock wrote: “Made two Snow balls, a refreshing bite at

this time of year.”

At 3 p.m.,

the pioneers crossed Muddy Fork, a stream about twelve feet wide, and camped on

its banks. Tall grass that resembled

wheat was plentiful. The mountain fever

continued to afflict the camp. As some

of the members got better, others became ill.

Wilford Woodruff came down with it and also William Carter.

Many of the other brethren spent the evening singing hymns for Brigham

Young.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

Thomas

Grover, William Empey, John Higbee, and Jonathan Pugmire (of the battalion) did

about $30.00 worth of blacksmithing.

Appleton Harmon helped repair Edmund Ellsworth’s wagon. Luke Johnson performed dentistry. Benjamin F. Stewart herded cattle. Francis M. Pomeroy searched for his

horse. Edmund Ellsworth and James

Davenport were sick.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The

Jedediah M. Grant Hundred was delayed because of a broken wagon. They watched the other companies disappear

out of sight. The company later caught

up and camped on the banks of the Platte.

Some of the men went to hunt buffalo during the day, but returned to the

wagon without spotting any. The camp

had to take a slightly different route than Brigham Young’s pioneer camp,

because the waters were higher and more mud slues had to be avoided. Jesse W. Crosby waded across the

Platte. He wrote: “Found it one mile wide, three feet deep,

one foot on an average, current three miles an hour.” Several of the sisters washed in the warm water and noticed a

large pine tree floating down the river.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

Mary

Richards and Amelia Peirson Richards (wife of Willard Richards) took a walk on

the bluffs above Winter Quarters. She

wrote: “We gazed with delight upon our

city of 8 months growth its beauty full gardins and extensive fields clothed

with the fast growing corn and vegetables of every description above all things

pleasing to the eyes of an Exile in the Wilderness of our afflictions.”

A

daughter, Mary Eliza Johnson, was born to Aaron and Mary Johnson. Mary Amanda Margaret Zabriskie, age five

months, died. She was the daughter of

Louis C. and Mary Higbee Zabriskie.

Kearny detachment

of the battalion, in Idaho:

The

detachment crossed into present‑day Idaho. They traveled thirty miles and camped at Big Spring.

Mormon Battalion,

at Los Angeles, California:

The

natives were very busy preparing the town for another Catholic

celebration. The battalion received

rumors that the Mexicans might try to use the festival to recapture the city by

drawing the battalion out of their fort.

Several brass cannons were brought in from San Pedro.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, at San Diego, California:

Company B

took up their march for Los Angeles, departing their home in San Diego for

almost four months. Then natives hated

to see them leave and clung to them like children. The company traveled twelve miles and camped.

Sources:

“The Journal of

Nathaniel V. Jones,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:21; Howard Egan Diary,

Pioneering the West, 93‑4; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West,

40; “Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement Era 15:249; Kenney,

ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:226; Watson, ed., The Orson Pratt

Journals, 440‑41; Bagley, ed., The Pioneer Camp of the Saints,

222; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters, 151; The Personal Writings of Eliza

Roxcy Snow, 183; “Jesse W. Crosby Journal,” typescript, BYU, 35; Smart,

ed., Mormon Midwife, 90; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 4:110; Ricketts, The Mormon Battalion, 158; Tyler,

A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion, 297

Saturday, July 10, 1847

West of Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

The

pioneers traveled a road that gradually ascended. They passed a spring which they named Red Mineral Spring. It was very red and the water tasted

terrible. They soon reached the summit

of a ridge. Orson Pratt calculated the

elevation at 7,315 feet. They then

descended into a valley and halted for the noon rest. Thomas Bullock wrote:

“Mr. [Lewis] Myers caught a young ‘War Eagle’ & brought it into Camp

to look at. It measured 6 feet between

the tips of its wings.”

In the

afternoon, the pioneers had to climb another ridge that ran between Muddy Fork

on the east and Bear River on the west.

The elevation of this summit was believed to be 7,700 feet. They descended into the valley and camped on

Sulphur Creek. Thomas Bullock recorded:

Descended

by two steep pitches, almost perpendicular, which on looking back from the

bottom looks like jumping off the roof of a house to a middle story, then from

the middle story to the ground & thank God there was no accident

happened. President Young & Kimball

cautioned all to be very careful & locked the Wheels of some wagons

themselves. It was a long, steep &

dangerous descent.

An Indian

came from Fort Bridger and camped with the pioneers for the night. Three grizzly bears were spotted but they

quickly left and did not bother the camp.

Albert Carrington found a vein of stone coal despite statements from

explorers who said it would not be found in this region.

Orson

Pratt recorded:

Just before

our encampment, as I was wandering alone upon one of the hills, examining the

various geological formations, I discovered smoke some two miles from our

encampment, which I expected arose from some small Indian encampment. I informed some of our men and they

immediately went to discover who they were; they found them to be a small party

from the Bay of St. Francisco, on their way home to the States. They were accompanied by Mr. Miles Goodyear,

a mountaineer. . . . Mr. G[oodyear] informed us that he had just established

himself near the Salt Lake, between the mouths of Weber’s Fork and Bear River;

that he had been to the Bay of St. Francisco on business & just returned

with this company following the Hastings new route [that traveled south of

Great Salt Lake into Nevada] that those left in charge at the lake had

succeeded in making a small garden which was doing well by being watered.

Goodyear

estimated that they were seventy‑five miles from the lake. He described

three roads to reach the Salt Lake and spoke of the country. They discussed the tragic circumstances

surrounding the Donner‑Reed party who had traveled this road a year

earlier. Wilford Woodruff recorded in

his journal that he understood they were mostly from Independence and Clay

County Missouri and had been threatening to drive out the Mormons from

California. Elder

Woodruff wrote: “The snows fell upon

them 18 feet deep on a level & they died & eat up each other. About 40 persons perished & were mostly

eat up by those who survived them. Mrs.

L[avinah] Murphy of Tenn whom I baptized while on a mission in that country but

since apostitized & joined the mob was in the company, died or was killed

& eat up.” They were told that the

Donner‑Reed party had lost time quarreling who would improve the roads.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

Luke

Johnson shot a buffalo about three miles from the ferry. An emigrant company bought the meat from

him. The brethren at the ferry

purchased $100 worth of goods from a Mr. H. Lieuelling. The ferrymen were interested to find out

that he had a roadometer attached to one of his wagons.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The second

company of Saints traveled only about eight miles and camped early for the

weekend near an island full of willows.

Hunters were sent out, hoping to kill some buffalo, but they came back

only with some antelope and deer. They

were about 252 miles from Winter Quarters and about 700 miles behind Brigham

Young’s pioneer company at Sulphur Creek.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

An

important meeting was held under the direction of Isaac Morley. The objective was to reorganize the

companies at Winter and Summer Quarters.

This was needed because many of the captains and families had left for

the west. James W. Cummings and Benjamin

L. Clapp were sustained as captains of hundreds. The captains of fifty chosen were: Jonathan C. Wright, George D.

Grant, and Daniel Carn.

A son,

Thomas James Foster, was born to George and Jane McCullough Foster.

Summer Quarters,

Nebraska:

A son,

Isaac Houston Jr., was born to Isaac and Theodocia Keys Houston.

Mormon Battalion,

at Los Angeles, California:

A bull

fight was held on the flat near the town.

The battalion remained at the fort, but could still view the sports

below the hill. A grand ball was also

held and the battalion was invited. But

they remained at the fort because of rumors that the Mexicans were trying to

draw them out and take over the fort.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, marching to Los Angeles:

As they

were marching along the ocean, Robert Bliss and David Rainey noticed something

large and white in the distance. They

let their animals graze and went to check it out. It turned out to be about one hundred acres of salt, about a half

inch deep. Robert Bliss brought back a

pint of the beautiful salt. Company B

marched thirty miles and arrived at San Luis Rey.

Sources:

Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 441‑43; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s

Journal, 3:227; “Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement Era

15:250; Kelly, ed., Journals of John D. Lee, 186‑87; Cook, Joseph

C. Kingsbury, 119; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 40; Bagley, ed., The

Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 223; Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 90; Emigrant’s

Guide; Our Pioneer Heritage, 6; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 4:110; Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon

Battalion, 297

Sunday, July 11, 1847

West of Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

The

pioneers rested for the Sabbath. Some

of the brethren rode out to scout the route ahead and found a mineral tar

spring fifteen miles from camp. Some of

them thought it was oil. It had a very

strong smell. Albert Carrington tested

the substance and said it was 87% carbon.

Some of the men filled up their tar buckets and used it for wheel

grease. Others used it to oil their

guns and shoes. The substance burned

bright like oil. They also found a

sulphur spring nearby. William Clayton

wrote: “The surface of the water is

covered with flour of sulphur and where it oozes from the rocks is perfectly

black.”

As the

pioneers were getting closer to their new home, some started to feel uneasy

about the location. Thomas Bullock

recorded: “As I lay in my wagon sick, I

overheard several of the brethren murmuring about the face of the country,

altho’ it is very evident, to the most careless observer, that it is growing

richer & richer every day.” William

Clayton also heard this talk: “There

are some in camp who are getting discouraged about the looks of the country but

thinking minds are not much disappointed, and we have no doubt of finding a place

where the Saints can live which is all we ought to ask or expect.”

Miles

Goodyear went with Porter Rockwell, Jesse C. Little, Joseph Matthews, and John

Brown to show them a new road that would be shorter to the Salt Lake

valley. After dark, the brethren were

called together to decide which of the two roads to take. They decided to take a road that headed to

the right that Miles Goodyear recommended. The Twelve privately felt that the other

route would be safer, but decided to let the voice of the camp decide to avoid

further murmuring. A singing meeting

was held during the evening.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The brethren

ferried across seven hundred fruit trees, which included apple, peach, plum,

pear, currants, grapes, raspberry, and cherries. They were owned by Mr. H. Lieuelling of Salem, Iowa.

Phinehas

Young, Aaron Farr, George Woodward, Eric Glines, and battalion members William

Walker and John Cazier arrived at the ferry.

They had been sent back by the pioneers to help pilot the second pioneer

company who were about 400 miles to the east.

This small group had left the pioneers at Green River on July 4 and had

traveled all the way to the Mormon Ferry in just six days, a journey of about

215 miles.

Some of

the ferrymen wanted to join this company to meet their families. Since the river was low enough to ford, and

most of the Oregon emigrants had already passed, Thomas Grover agreed with this

idea. The brethren decided to divide

equally all of the provisions that the ferrymen had received. The division amounted to $60.50 each.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

Hunters

were sent out to hunt buffalo. Eight

were later brought in. A public Sabbath

meeting was held at 1 p.m.

Sarah Rich

wrote in her autobiography:

We

journeyed on up the Platte River, came into the buffalo country, seeing many

large buffalo. Brother Lewis Robinson

was the first one in our company to kill a buffalo. He killed one weighing over a thousand pounds. We all stopped and had a feast all through

our camp. We stopped a few days to

wash, iron and cook, while the men repaired their wagons, and let their teams

rest and recruit up as we were in good food.

When all the companies would come up, we would start on again.

The second

death on the pioneer journey from Winter Quarters occurred. Ellen Holmes, of the Daniel Spencer company,

died. She had been ill for six months.

Winter Quarters,

Nebraska:

Elder

Orson Hyde preached at a Sunday meeting.

His topic was, “There is a way that seemeth good unto man but leadeth

unto death.” He said that all

disobedient and unruly spirits would be servants in the next world. Friend Gilliam was quite offended by this

sermon. In the evening, the High

Council met. They discussed Daniel

Russell’s order to Hosea Stout to disband the guard. Many of the Council that an order had been issued, because they

had never discussed the subject. They

all agreed that the guard should still be kept.

Mormon Battalion,

at Los Angeles, California:

The bull

fights continued in Los Angeles.

Several horses were gored in the games.

One of the bulls broke out of its pen and caught Captain Daniel Davis’

six-year-old boy, Daniel, with its horns and was said to have tossed him twenty

feet in the air. The little boy was

bruised and scared.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, marching to Los Angeles:

The men visited

the mission and then marched eleven miles and camped at San Bernardo de Los

Floris, near the ocean. They visited a

church and Indian village.

Sources:

Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:227; Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering the West,

94; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 40; “Journal of William Empey,” Annals

of Wyoming, 21:139; Kelly, ed., Journals of John D. Lee, 187;

“Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement Era 15:259; Bagley, ed., The

Pioneer Camp of the Saints, 224; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier,

1:265; William Clayton’s Journal, 289‑90; The Personal Writings

of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 183‑84; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 4:111; Ricketts, The Mormon Battalion, 159;

1997‑98 Church Almanac, 117; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,” typescript,

BYU, 74

Monday, July 12, 1847

West of Fort

Bridger, Wyoming:

Wilford

Woodruff got up early and rode to Bear River to do some early‑ morning

fly fishing. “For the first time I saw

the long looked for Bear River Valley.

Yet the spot where we struck it was nothing very interesting. There was considerable grass in the valley

& some timber & think bushes on the bank of the river.” He found it difficult to fish with the fly

because of thick underbrush, but he wrote:

“I fished several hours & had all sorts of luck, good, bad, and

indifferent.”

The rest

of the pioneers started out, and traveled down Sulphur Creek and came to the

Bear River. It was about sixty feet

wide and two and a half feet deep. The

current was rapid and the bottom was covered with boulders, presenting a

difficult crossing.

They came

to another fork in the road and took the road to the right. The road climbed over a ridge and then they

descended into a ravine which they followed for several miles. Orson Pratt described their surroundings: “The country is very broken, with high hills

and vallies, with no timber excepting scrubby cedar upon their sides.” Erastus Snow added: “There has been a very evident improvement

in the soil productions and general appearance of the country since we left

Fort Bridger, but more particularly since we crossed Bear River. The mountain sage has in a great measure

given place to grass and a variety of prairie flowers and scrub cedars upon the

sides of the hills.”

The

hunters brought in about a dozen antelope from a large heard. The pioneers came to “The Needles,” some

rock formations that Orson Pratt described these formations: “The rocks are from 100 to 200 feet in

height, and rise up in perpendicular and shelving form, being broken or worked

out into many curious forms by the rains.

Some quite large boulders were cemented in this rock.”

Brigham

Young became very sick with the mountain fever. He decided to stop a few hours to rest. The rest of the wagons stopped with him for the noon rest, but

after two hours the majority were told to continue. Eight wagons stayed behind, including Brigham Young, Heber C.

Kimball, Lorenzo Young, Ezra T. Benson, and Albert P. Rockwood. Brother Rockwood was also very sick.

The rest

of the company traveled down a ravine and then crossed over another ridge. They descended into another ravine and

camped at the foot of a ledge of rooks.

Orson

Pratt wrote: “Here is the mouth of a

curious cave [Cache Cave]. . . . The opening resembles very much the doors

attached to an out‑door cellar, being about 8 feet high and 12 or 14 feet

wide. . . . We went into this cave about 30 feet, where the entrance becoming

quite small, we did not feel disposed to penetrate it any further.” Wilford Woodruff added: “Many of us cut our names in it.” They named the cave “Redden’s Cave,” after

Jackson Redden, the first of the pioneers to find it. Brigham Young and the others did not come into camp by the

evening.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

Many of

the brethren prepared to return to Fort Laramie with those sent back from the

Pioneer company and the Mormon Battalion.

Two buffalo were spotted on the north side of the river coming toward

the ferry crossing. Luke Johnson and

Phinehas Young chased them and soon killed one of them only a half mile from

camp. The meat was brought into camp

and dried.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The Daniel

Spencer Hundred took their turn to lead the more than 1,500 pioneers. Eliza R. Snow wrote: “The prairie to day is little else than a

barren waste ‑‑ where the buffalo seem to roam freely.” They traveled about twelve miles and

camped. Many of the men were busy

smoking buffalo meat. They obtained

wood by wading over the river to Grand Island.

Isaac C. Haight burned his foot badly.

Sarah Rich

wrote:

But while

passing through the buffalo country we did not travel fast, for all the men

folks seemed to want to kill a buffalo, so they would travel a few miles a

camp, and hunt, for it was a new sport for them. Mr. Rich was after a large herd, him and several of our company,

riding horse back. They killed

three. The first one he wounded; it was

a very large one, and it turned upon him and came very near killing the horse

he was riding, but Mr. Rich shot again, and killed the buffalo. The next day he killed two more. They dressed them and divided out the meat

in the company. The men fixed scaffolds

out of willows and spread out the meat cut up in thin slices, and made fires

underneath, as one side of the meat would get dry, they would turn it over, and

by so doing, it became dry. They called

it "jerk" meat. We put it

into sacks, and had enough to last us all through and it was the sweetest meat

I ever tasted. The children grew fat on

it. We also tried out the tallow, for

we needed grease for our cooking. Every

other company also supplied themselves with "jerked" meat.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, marching to Los Angeles:

Robert S.

Bliss wrote: “Marched 16 miles side of

the ocean & in it when every few waves would wet our horses feet. I selected a few shells for a memorial of

the Great Pacific.” They camped near the

ruins of the San Juan Mission.

Sources:

Watson, ed., The Orson

Pratt Journals, 443‑45; “Luke S. Johnson Journal,” typescript, BYU,

16; “Erastus Snow Journal Excerpts,” Improvement Era 15:259; “Albert P.

Rockwood Journal,” typescript, BYU, 62; Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering the

West, 94‑5; Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:228‑29;

Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 40; “Journal of William Empey,” Annals

of Wyoming, 21:139; Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife, 90‑1; The

Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 184; “The Journal of Robert S.

Bliss,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:411; “Isaac C. Haight Journal,”

typescript, 42; “Sarah Rich Autobiography,” typescript, BYU, 74‑5

Tuesday, July 13, 1847

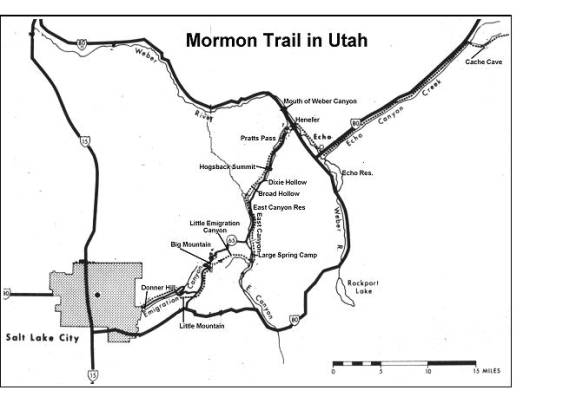

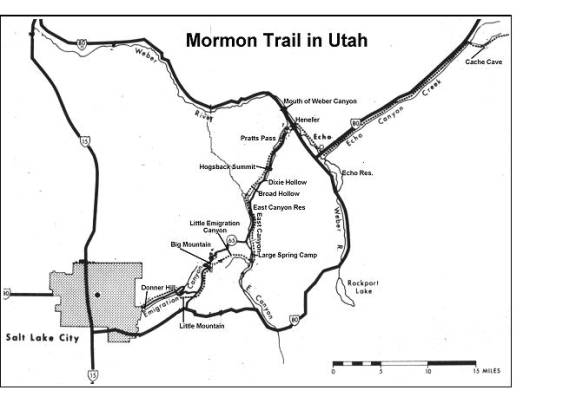

Near Cache Cave,

Utah:

Two

messengers, John Brown and Joseph Matthews, were sent back to meet with Brigham

Young back at The Needles. The camp did

not want to move on until President Young caught up with them. The messengers returned with Heber C.

Kimball and Howard Egan. They reported

that Brigham Young was feeling a little better but still could not travel. Albert P. Rockwood was near death and

“deranged in mind.”

It was

becoming very urgent for the pioneers to complete their journey and to plant a

crop as soon as possible in the Salt Lake Valley. The Twelve directed Orson Pratt to lead an advance company of 42

men and 23 wagons through the mountains.

They were instructed to make roads to enable the main company to follow

later. Heber C. Kimball returned to The

Needles. At 3 p.m., this company

started their journey and traveled about eight miles and entered Echo Canyon.

The main

company stayed at their camp near Cache Cave.

Thomas Bullock went to explore the cave which was thirty‑six feet

by twenty‑four feet and was about four to six feet high. Many of the brethren carved their names on

the walls. Brother Bullock observed

about fifty swallows nests near the roof of the cave.

The

hunters brought in twelve antelope.

Wilford Woodruff and Willard Richards took a walk to search for a

spring. They reminisced about their

missionary days when Elder Woodruff served at the Fox Islands in Maine, and

when they labored together in Preston, England. As the main camp rested in the evening, Thomas Bullock

wrote: “Our camp was stiller to night

than it has been since we left Fort [Laramie.]”

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The

ferrymen divided into two companies.

The first company would stay at the ferry and the second would journey

back to Fort Laramie to meet the second pioneer company. Those who stayed at the ferry were: William

Empey, John Higbee (who was sick), Appleton Harmon, Luke Johnson, James

Davenport, and Eric Glines (who had come back from the pioneers.) Those who

left for Fort Laramie were ferrymen, Thomas Grover, Francis M. Pomeroy, Edmund

Ellsworth, and Benjamin F. Stewart.

Also returning were: pioneers,

Aaron Farr, George Woodward, and Phinehas Young, and battalion members William

Walker, John Cazier, and Jonathan Pugmire.

After the

brethren left the ferry site, the rest were busy drying buffalo meat.

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The “Big

Company” of pioneers started the day’s journey at 7 a.m. They crossed a “multitude” of trodden down

buffalo paths that led from the bluffs to the river. Isaac C. Haight went to hunt buffalo. He chased a herd but fell off his horse and lost the chase.

Winter Quarters:

It was

very hot in Winter Quarters. Hosea

Stout’s last living child, Marinda Stout, born at Garden Grove, was very sick

and Brother Stout feared that she was dying.

Delia Ann

Covey, age one month, died of consumption.

Clarinda McCoulough, died of consumption. She was the wife of Levi McCoulough.

Kearny detachment

of the battalion, in Idaho:

The

detachment reached the Oregon Trail at noon, and followed it to the east,

toward Fort Hall. They reached the

Columbia River.

Company B, Mormon

Battalion, marching to Los Angeles:

During the

day the battalion company crossed over a plain where they saw about twenty

thousand cattle and horses grazing. The

hills could be seen covered with cattle, horses, sheep, and goats.

Sources:

Watson, ed., The

Orson Pratt Journals, 445; “Luke S. Johnson Journal,” typescript, BYU, 16;

Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:229; “Albert P. Rockwood

Journal,” typescript, BYU, 62; Howard Egan Diary, Pioneering the West,

95; “The Journal of Nathaniel V. Jones,” Utah Historical Quarterly,

4:21; Appleton Milo Harmon Goes West, 40, 41; “The Journal of Robert S.

Bliss,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:111; Bagley, ed., The Pioneer

Camp of the Saints, 225‑26; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier,

1:266; The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 184; Smart, ed., Mormon

Midwife, 91; “Isaac C. Haight Journal,” typescript, 42

Wednesday, July 14, 1847

Advance Company in

Echo Canyon, Utah

The

advance company traveled through Echo Canyon.

Orson Pratt wrote: “Our journey

down Red Fork has truly been very interesting and exceedingly picturesque. We have been shut up in a narrow valley from

10 to 20 rods wide, while upon each side the hills rise very abruptly from 800

to 1200 feet, and the most of the distance we have been walled in by vertical

and overhanging precipices of red pudding‑stone, and also red sand‑stone.” Levi Jackman added: “The valley was fertile but very narrow and

the hills on both sides were several hundred feet high. In many places it was difficult

passing. A little before night we

struck the Weber Fork and camped. We

came about 14 miles today.” Their plans

were to follow the Weber River to the valley.

Main Camp, near

Cache Cave, Utah:

Wilford

Woodruff and Barnabas Adams traveled back to the rear company, to see how the

sick were doing.

Thomas

Bullock sat in the cool cave all day and caught up on his writing. Many of the other brethren spent the day

hunting and killed several antelope.

Wilford

Woodruff returned in the evening and brought back news regarding the sick in

the rear company. A meeting was called

around Willard Richards’ wagon. It was

decided to hitch up and move the camp a short distance in the morning.

William

Clayton wrote about the mountain fever:

There are

one or two new cases of sickness in our camp, mostly with fever which is very

severe on the first attack, generally rendering its victims delirious for some

hours, and then leaving them in a languid, weakly condition. It appears that a good dose of pills or

medicine is good to break the fever.

The patient then needs some kind of stimulant to brace his nerves and

guard him against another attack. I am

satisfied that diluted spirits is good in this disease after breaking up the

fever.

Rear Company at The

Needles, Wyoming:

Wilford

Woodruff and Barnabas Adams visited the rear company of sick brethren. They were pleased to see that Brigham Young

was getting better and they ate supper with Heber C. Kimball. Wilford Woodruff planned to bring his

carriage from the main camp in the morning for Brigham Young and Albert P.

Rockwood to ride in.

Albert P.

Rockwood’s fever still raged and he was delirious. He later wrote: “Br

Lorenz Young and many others look upon me as dangerous ill. I so considered myself and so told the

brethren that if no relief came in 24 hours, they might dig a hole to put me

in.”

Howard

Egan, Heber C. Kimball, Ezra T. Benson, and Lorenzo Young climbed to the top of

a high mountain and offered prayers for the sick and for their families so far

away.

Mormon Ferry,

Wyoming:

The

ferrymen started to move their belongings, six miles up the river where the

feed was better. An emigrant company

arrived and needed some blacksmithing performed. All the blacksmith tools were moved up the river and set up for

business. Luke Johnson stayed at the

ferry site overnight to guard the rest of the things that had not yet been

moved up. During the night, he was bothered

by wolves that wanted to eat the buffalo meat.

Brother Johnson shot one, reloaded and fired again. “Then the gun burst. It burned his face and arm and hand

considerably, and slightly wounded his other arm and hand. A piece of the lock or something passed

through his hat with great violence, which closely grazed his head.”

On the Platte

River, Nebraska:

The

Jedediah M. Grant Company had difficulties and was delayed. During the night their herd broke out of the

yard and crushed two wheels on Willard Snow’s wagon, killed a cow, broke of

some horns, and broke the leg of a horse.

They had to spend the day repairing Brother Snow’s wagon. The Charles C. Rich company remained behind

with them. Abraham Smoot’s company

passed them during the day.

The

pioneers arrived at the location where the first pioneer company camped on May

9, 1847. They found the post,

guideboard, and box with a letter and history of the journey up to that

point. The guideboard stated that they

were 300 miles from Winter Quarters.