Brigham

Young and Willard Richards rode on horseback up Turkey Creek to view the site

for the mill. They visited President

Young’s brothers, John, Phinehas, and Joseph.

John Young was still sick and the brethren administered to him.

Elder

Richards received fifty dollars from Albert P. Rockwood to distribute among the

needy battalion families. Wilford

Woodruff was sick in bed from exhaustion due to the hard work of the previous

days, cutting house logs.

Mary

Richards wrote in her letter to her missionary husband, Samuel W.

Richards: “The place where we have

settled for winter quarters is one of the most beautyfull flatts I ever

see. It is about one mile square. The East side borders on the Mo River and

most of the North & South. The West

side is bounded with a ridge or bluff, from the top of which it decends

graduley to the River. . . . The scene is quite Romantic.” Mary was camping about a quarter mile from

the meeting ground and about a half mile from Willard Richards’ camp.

A daughter,

Mary Minerva Snow was born to Erastus and Minerva Snow.1 Felina Clark, age nineteen months, died of

fever and “fits.” She was the daughter

of Lorenzo and Beulah Clark.

Chandler

Rogers died at the age of fifty-one. He

was the father of nine children, including battalion member, Samuel Hollister

Rogers. Chandler’s wife, Amanda Rogers

wrote: “The last day [he] went to sleep as usual, died about 8 o'clock in the

evening. We feel very lonesome.”

A son,

Samuel Clark, was born to Samuel and Rebecca Clark.2

Almon W.

Babbitt, one of the Nauvoo Trustees, arrived at Garden Grove on his way to

Winter Quarters. He told the Saints

about the Battle of Nauvoo and the surrender of the city to the mob.

Distressing

news arrived that the mob proclaimed no Mormon would be allowed to cross back

over the river to sell property. They

vowed that no Mormon in the camp would get a cent for the property left

behind. This news caused a great deal

of concern and some murmuring among the destitute Saints.

The

battalion started their march at daylight, traveled three miles, and stopped at

Stillbitter Creek to graze the animals on the grass. After four hours, they resumed their march and traveled another

twelve miles, camping in a valley just east of Point of Rocks.3

During

their travels, they passed within a half mile of some walls of an ancient

structure to the north. Two walls ran

parallel, about four feet apart for about one hundred thirty feet. They appeared to be constructed with

cement. Daniel Tyler wrote:

Whether

these had been partition walls of a castle or some large building, or a part of

a fortification, it would be difficult to determine. It was evident that the whole face of the country had undergone a

change. There were numerous canals or

channels where large streams had once run, probably for irrigating, but which

were then quite dry, and to all appearance had not been used for generations.

In the

evening, Lt. Smith cursed the sergeants and Quartermaster Samuel Gully for

neglecting their duties.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 402; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:90;

“Allen Stout Journal,” typescript, BYU, 26; Journal of Henry Standage in

Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion, 168; Yurtinus, A Ram in

the Thicket, 160; Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion,

162; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters,

92; Our Pioneer Heritage,

3:167‑68

In the

morning, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards went to see John

Pack, who had just returned from Savannah, Missouri. Brother Pack had brought back the carding machine purchased by

the Church and also brought back two newspapers. Peter G. Camden, of St. Louis, Missouri, published a sympathetic

appeal to the citizens of the city for the poor who had been driven from

Nauvoo. The newspapers announced that

food clothing and other articles were being collected for the sufferers. The stores of J.P. Eddy and Beebe Bros. were

advertised as locations accepting contributions.

At noon,

President Young, Willard Richards, and Albert P. Rockwood rode out to see the

brickyard. They also saw an excellent

bed of clay and stone in the river which could be used for wells.

In the

evening, a council meeting was held at Brother Rockwood’s tent. A report was read regarding the herding of

cattle. Amasa Lyman, Orson Pratt, and

Wilford Woodruff were appointed as a committee to divide the city into

wards. Bishops would be appointed over

each ward and would take care of the poor.

Benjamin L. Clapp was appointed to superintend the building of a house

to store the carding machine.

The High

Council met and discussed Brigham Young’s request that they send more men and

teams to help gather the poor from the banks of the Mississippi River. Even though the brethren in Council Bluffs

were already carrying the load for providing for the Mormon Battalion families,

they responded favorably to this request for additional service. James Murdock and Allen Taylor, with about

twenty‑five more teams, would lead this rescue effort. These teams would be in addition to those

led by Orville M. Allen, who left about two weeks earlier. Brother Allen’s rescue team would arrive in

the poor camp within a few days.

A son,

Joseph Lewis Ford, was born to William and Delana Ford.

Members of

the camp started to move away from the river to other locations nearby that

were believed to be healthier. Many

cranes were seen flying south.

Joseph

Heywood, one of the Nauvoo Trustees, wrote a letter to Brigham Young. He reported that he had gone to St. Louis to

solicit aid for the destitute Saints, “whose situation is truly deplorable

scattered along the bank of the river opposite to Nauvoo.” He reported that he had been somewhat

successful in finding aid. Also, he

found a man who might be interested in buying the temple. He hoped that they could finish up the work

in Nauvoo soon, because it was “like the abomination of desolation.” The mob had searched his home in Nauvoo

while he was away, but they did not find his most valuable arms.

While the

battalion halted its march for breakfast at spring near Point of Rocks, Levi

Hancock and others climbed the highest peak.

Brother Hancock built an altar and offered prayers. He also broke off some branches from the

highest cedar tree which he gave to his friends. The rest of the battalion marched on for two miles to water the

animals.

In the

afternoon, the battalion met a company of dragoons coming from Santa Fe. They reported that General Kearny left for

California on September 25 and said that the Mormon Battalion would have to be

discharged if it did not reach Santa Fe by October 10. As a result, the battalion marched long and

hard for a total of twenty‑seven miles to Red River.

A problem

arose when a number of men were reported by their Mormon officers and put under

guard for falling behind the line of march and for other violations. John D. Lee defended the soldiers and argued

that no officer in the Battalion could court martial another legally. He still contended that Lt. Smith did not

have legal command of the battalion.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 403, 432; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier,

The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 203; Yurtinus, A Ram in the

Thicket, 161; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical

Quarterly, 4:73‑4; Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 1846‑1852,

82‑4; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp

Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the Saints

John Hill

and Asahel Lathrop arrived from their camp about seventy miles up the Missouri

River. They, along with seven other

families had left George Miller’s company at Ponca, who were still about 150

miles up the river. They had become

discontented with Bishop Miller’s leadership and moved further south to find

better feed for their cattle. During

the last six days of their journey to Winter Quarters, Brothers Hill and

Lathrop lived on two squirrels, one goose and a turtle.

The

lowlands near the river were full of men and teams cutting cottonwood trees for

house logs. Hosea Stout traveled six

miles up the river where the camp’s herd was being kept. On Saturdays, the men would gather the

entire herd scattered over several miles.

This made it much easier for the owners to find their cattle. Otherwise it might take a week to search for

specific cattle.

A son,

John Helaman Pixton, was born to Robert and Elizabeth Cooper Pixton.4

After

traveling for about six miles in the morning to Ocate Creek,5 Lt. Smith called for a

temporary halt and invited all the battalion officers to his tent. Lt. Smith emphasized the importance of

arriving at Santa Fe within a week. He

proposed that fifty strong men from each company make a quick, forced march to

Santa Fe. The sick, lame, women, and

children would be left behind under the command of Lt. George Oman. Most of the officers agreed to this

proposal.

The

recognized religious leaders of the battalion, Levi Hancock, David Pettigrew,

and John D. Lee strongly opposed this proposed division. Many of the enlisted men were about ready to

revolt when they heard of this decision.

But Captain Jefferson Hunt said to his men that he thought “this to be

the best move that could be made.”

Private George W. Taggart expressed his feelings, “I did not feel like

volunteering to go on and leave the sick behind, consequently I did not go with

the first division.” Robert Bliss

wrote, “I fear treachery.”

So the

battalion became divided and the advance group traveled on for another eighteen

miles and camped on Wagon Creek near a high rock. Some of the Missouri Volunteers were camped there. A few Mexicans and Indians entered the camp

in an attempt to sell whiskey and other items.

It is

interesting to note, but not surprising, that Dr. Sanderson chose to go ahead

with the healthy men rather then staying behind to care for the sick. Daniel Tyler wrote: “But the sick did not complain on that

score. The sorrow which they felt at

the loss of friends through having the Battalion divided was in a great measure

compensated by the relief they experienced at being rid of the Doctor’s drugs

and cursing for a few days.” There

would be a noticeable improvement in the health of those who stopped taking the

drugs.

Elders

Orson Hyde and John Taylor arrived in Liverpool, England. They had experienced some severe gales at

sea and witnessed the wrecking of three vessels in the middle of the ocean. Their ship had saved half of the passengers

from one of the other ships.

Elders

Hyde and Taylor immediately issued a circular to the Saints. They stated that they had been sent by the

Council of the Twelve to “set in order” every department of the Church, in

England. They advised the Saints to no

longer patronize the Joint Stock Company which had been misused by the brethren

who had been left in charge of the British Mission. It was made clear that the Stock Company was independent from the

Church. A conference was appointed to

be held at Manchester, England, on October 17, where more instructions would be

given.

Reuben

Hedlock, who had been left in charge of the British mission, had fled to

London. Elder Taylor later wrote of

this man:

Elder

Hedlock might have occupied a high and exalted situation in the Church, both in

time and eternity; but he has cast from his head the crown ‑‑ he

has dashed from him the cup of mercy, and has bartered the hope of eternal life

with crowns, principalities, powers, thrones and dominions, for the

gratification of his own sensual appetite; to feed on husks and straw‑‑to

wallow in filth and mire!

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 403, 493, 597; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 203; Journal of Henry

Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion, 169; “William

Coray’s Journal”; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 161; “The Journal of

Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74; Tyler, A

Concise History of the Mormon Battalion, 163; Roberts, The Life of John

Taylor, 178

A Sunday

meeting was held at the stand in Winter Quarters. Elder Orson Pratt preached on the first principles of the gospel

to the congregation consisting several nonmembers. Letters were read including some from the Mormon Battalion.

After the

morning session, Elders Orson Pratt, Amasa Lyman, and Wilford Woodruff divided

Winter Quarters into thirteen wards.

Bishops were appointed over each ward.

They ordained six of the bishops at that time.

In the

afternoon, the Saints again assembled to hear President Brigham Young

speak. He mentioned that John Hill and

Asahel Lathrop arrived from their camp about seventy miles up the Missouri

River. They had broken off with Bishop

Miller’s camp because of “oppression and disorder.” President Young said he intended to send his cattle up to Brother

Hill and Lathrop’s camp for the winter.

He advised that some families be sent up there to winter their cattle at

that location.

President

Young discouraged participating in the practice of paying visiting peddlers

inflated prices for goods. He proposed

that a committee be appointed to purchase goods collectively from the

merchants. If the prices were still too

high, they would not buy their goods.

Volunteers were asked for to help build a bridge. Brethren were given the opportunity to

advertise for help to find their lost animals or property.

In the

evening, a council meeting was held.

Elder Willard Richards reported on the plot of Winter Quarters which had

been drawn by Elder Orson Pratt.

Halmagh

Van Wagoner, age fifty-nine, died. He

was the husband of Mary Ann Van Houten Van Wagoner.

It was

rumored that the mob had removed the angel weather vane and the ball from the

top of the temple.6 Thomas Bullock wrote: “At night I took a walk thro the Camp for

the first time and counted 17 tents and 8 Wagons remaining, and most of those

are the poorest of the Saints. [There

is] not a tent or Wagon but [has] sickness in it, and nearly all don’t know

which way they shall get to the main camp.”

The

advance companies of the battalion traveled about twenty‑four miles and

arrived at Wolf Creek.7 They found good water and grass at this

location. Lt. Smith restored full

rations to this advance group of troops.

Some Mexicans came into the camp to sell cakes and bread.

Abner

Blackburn wrote of an event that probably occurred at this time.

Camped one

afternoon about three oclock. Presently

there rode up several Spainiards.

Amongst them was a Spanish Hidalgo and his daughter with their rich

caprisoned horses and their jingeling uniform.

The [Senorita] lit off her horse like a nightengale. The whole camp was there in a minute. Their gaudy dress and drapery attracted all

eyes. The dress of the [Senorita] is

hard to describe, all the colors of the rainbow with ribbons and jewelry to

match. . . . We gave them presents and made them welcome to our camp and also

to martial music as a greeting. The

damsel was struck with our drummer boy, Jesse Earle, and his violin. He played “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” She could not contain herself and with her

companaros started a dance and made the dance fit the tune. . . . She took a

fancy to our drummer boy. The

attachment was mutual; but his admiration cooled off somewhat when she

appropriated his handkerchief and pocket‑knife.

The rear

companies of the battalion traveled about eighteen miles and camped at Wagon

Mound in a beautiful valley they called the Valley of Hope. Good grass was found for the teams.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 404‑05 Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:91; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

203; Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

169; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 165, 173; “The Journal of Robert S.

Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74 “Norton Jacob

Autobiography,” BYU, 42‑43; Bagley. Frontiersman, Abner Blackburn’s

Narrative, 41‑2; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer

Camp of the Saints

Brigham

Young visited the sick and finished his well that was thirty‑two feet

deep. The High Council met and

appointed a committee to purchase sheep.

Wilford

Woodruff left Winter Quarters in the morning in his carriage to take four or

five sisters on a “graping expedition.”

They crossed over the river on the ferry and traveled to Council Point. On the way, Elder Woodruff shot three

prairie chickens and they arrived at the grape fields at dark. Elder Woodruff built a fire and fetched

water from the Missouri River. The

women made their beds in and under the wagon.

Elder Woodruff tried to sleep under the stars, but the moon was shining

bright, keeping him awake. At midnight

he went to the river for several hours to hunt.

A

daughter, Susan Burgess, was born to Horace and Iona Burgess.

A son,

William Thomas Ewell, was born to William and Mary Ewell.8

The Saint

Louis Weekly Reveille reported that Joseph L. Heywood, one of the Nauvoo

Trustees, was in the city asking for provisions to help the poor who had been

driven from Nauvoo.9 “We know their wretched state, not from

report, but from eye witness, of misery which is without a parallel in the

country. They are literally starving

under the open heavens; not even a tent to cover them‑‑women and

children, widows and orphans, the bed‑ridden, the age‑stricken and

the toil worn.” The article asked for

clothing and money to be donated to help the Saints.

A very

pleasant day cheered up the sick and hungry Saints. Thomas Bullock wrote, “A very fine day, the woods all alive with

the sweet music of birds which makes me feel delightful even in my exiled

state.”

An issue

of the Hancock Eagle was published by the non‑Mormon new citizens

of Nauvoo. It reported that the anti‑Mormons

were in violation of the treaty because they had in effect stolen the guns from

the Mormons. “It is no exaggeration to

say that nineteen‑twentieths of the arms delivered have been

confiscated.”

The Nauvoo

Temple had sustained much damage from the mob.

“Holes have been cut through the floors, the stone oxen in the basement

have been considerably disfigured, horns and ears dislodged, and nearly all

torn loose from their standing.” Names

had been carved in the woodwork of the large assembly room on the main floor.

The

advance companies of the battalion traveled about thirty miles, and camped near

a Mexican town called Las Vegas. The

town was relatively large with a population of about five hundred people. Samuel Hollister Rogers wrote: “The houses are rudly built chiefly of

adobies, a kind of large sun‑dried brick, one storey high with a flat

roof made by laying line poles across with brush and covering with mortar. Only saw one window in the whole town. When we passed through the men, women and

children came into the street to see us.

Some climbed upon the roofs of the houses.”

Abner

Blackburn wrote that the inhabitants of the town were “a most miserable set of

poor, half clothed wretches, covered with vermin, who cared for nothing except

a few meals and a Fandango to kill time.

The rich were very rich and the poor very poor and worthless.” Their fields were near the river

bottoms. Irrigation was used to water

the crops of wheat, squaw corn, onions, red peppers and squash.

The rear

companies broke camp at noon and traveled twenty‑five miles until

midnight when they reached the Noro River.

They camped near a small Mexican settlement.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 405‑07; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:91; Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

169; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 165‑66, 173; “The Journal of

Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74 Our Pioneer

Heritage, 20:181; Bagley, Frontiersman, Abner Blackburn’s Narrative,

42 “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the

Saints

Work

commenced on a dam for the Winter Quarters flouring mill. Almon W. Babbitt, one of the Nauvoo

Trustees, arrived at Winter Quarters with forty‑four letters and one

hundred newspapers. He reported that

the mob had taken over Nauvoo, had most of the brethren’s guns, and had defaced

the temple. Many of the poor families

had gone on to St. Louis, Missouri.

Helen Mar

Whitney wrote of Brother Babbitt’s news of mob activities, “They had several

mock ceremonies with different individuals, and had baptized or dipped Moses

Davis three times. . . . The shore of the city and nearly all the approaches to

the city, were strickly guarded, to prevent the ingress of Mormons, and when

any man was found they immediately baptized him and sent him over into

Iowa.”

A letter

was received from Bishop Newel K. Whitney who had visited the poor camp near

Montrose, Iowa, on his way to St. Louis.

(See September 20, 1846.)

He reported the destitute condition of the Saints and that about fifty

wagons would be needed to help bring the poor further to the west.

Lorenzo

Dow Young went up the river twelve miles with six others to pick grapes. They made their camp as comfortable as

possible. He wrote, “We had a little

music from the wolves, to remind us we were not alone.”

A

daughter, Charlotte J. Cole, was born to John and Charlotte Cole.10

Ashabell Dewey, age fifty-one, died of canker. He was the husband of Harriet Dewey. Ann Wadsworth, age thirty-six, died of canker and fever.

Wilford

Woodruff ate a breakfast of prairie chicken stew on the east side of the river

while on a graping expedition. He

recorded: “Found the grapes on

Cottonwoods & willows. I cut down

several hundred of them during the day the size of my arm & leg. And we all laboured hard untill sun set

picking grapes. We picked over three

Barrels of Bunch grapes & started for home by moon light. We returned as far as the ferry but could

not cross and had to camp for the night.”

Alonzo

Merrill, the eldest son of Albert Merrill died. The Merrill family were among those who experienced severe

hardship. Brother Merrill wrote:

My wife

continued to grow worse and her milk dried up.

Her young babe was without mother’s food and all the other children came

down with chills and fever. We could

not get help. The other people there

were many of them sick. One George

Bratton drove a yoke of my oxen from the range and took them up to the Bluffs

80 miles from our place. My horse that

my wife and children drove in a light wagon fell into a ravine and died in

sight of our place as I was not able to care for my stock.

A

daughter, Martha Zabriskie Doremus, was born to Henry and Harriet Doremus.

Elder

Jesse C. Little wrote a letter to Brigham Young reporting that he had just met

with President James K. Polk and found that the president had good feelings

toward the Saints. He asked the

president to appoint Jefferson Hunt or Sheriff Jacob Backenstos to lead the

Mormon Battalion, but the president said he did not have the power to appoint,

that the battalion would have to choose.

Elder

Little also visited with the Indian Commissioner and requested permission for

the Saints to remain on Indian lands for some time. Everything looked fine.

Elder Little earlier called upon Judge Kane and he offered his support

to help with anything in Washington on behalf of the Saints. “He wished me to say when I wrote to our

people that his son had expressed his highest regard for your great kindness

during his sickness of which he said much.”

His son, Thomas L. Kane had traveled to Washington, reported on the

barbarous treatment in Nauvoo, and worked to help the Saints receive permission

to stay on Indian lands.

The

battalion passed through the town of Las Vegas, marching to music in good

order. After about twelve more miles

they also marched through the town of Tecolotte. They made their camp on a farm near Burnetts Springs, five miles

from the town.11 While marching, they met a Mr. Simington who

was sent from Santa Fe by order of General Stephen Kearny. The message confirmed the order that the

battalion should arrive at Santa Fe by the 10th to received further

instructions from General Alexander Doniphan.

The rear

companies of the battalion rested this day.

From the top of a large rock near their camp, the soldiers were able to

see Lt. Smith’s division marching in the distance.

A son,

Ephriam Burdick, was born to Thomas and Anna Burdick.12

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 407‑08, 433; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:91; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 14:148 Woman’s

Exponent, 13:131; “Albert Merrill, autobiography,” typescript, BYU, 4;

Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

169; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 166‑67, 174; “The Journal of

Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74

Brigham

Young and other members of the Twelve traveled several miles to the north, to

the location where the herds were being tended. President Young wanted all those who were not herding regularly

to leave the herd grounds. He made

arrangements for the herdsmen to receive better clothes to perform their

duties. On the way back to Winter

Quarters, the brethren inspected the progress at the mill site.

Wilford

Woodruff returned to Winter Quarters and started to work at juicing the grapes

which had been gathered on his expedition.

They were able to obtain about twenty gallons of juice. Lorenzo Dow Young also returned from some

grape fields. As they left the fields,

he had difficulty finding his wagons because the willows and cottonwoods were

so thick. After quite some time, he

found them, and was on his way back to Winter Quarters. When he returned, he found his wife, Susan

Ashby Young, weeping. She had recently

received news of her father’s death from Brother Almon Babbitt. Brother Young did all that he could do to

comfort his dear wife. Her father,

Nathaniel Ashby had died near Bonaparte, Iowa, on September 23.

In the

evening, Brother Asahel Dewey was buried.

Several of the Twelve met at the post office to meet with Almon

Babbitt. Brother Babbitt was counseled

to return to Nauvoo, sell the Church property without delay, and to also sell

the property at Kirtland, Ohio. The

brethren discussed a rumor that Reuben Hedlock, who had been left in charge of

the British Mission over the Winter, had taken $7,000 dollars credit from the

Church and fled to unknown parts.

Willard

Richards called on his daughter‑in‑law, Mary Richards, and asked

her to go take care of Sister Eliza Ann Peirson, who was very sick.

A son,

Silas William Holman, was born to James and Naomi Holman.13

Orville M.

Allen, captain of the first rescue teams to help the poor, arrived at the camp

on the Mississippi River, across from Nauvoo.

He called the Saints together and informed them that he had been sent by

the Twelve to help. He told them, “I

was sent to bring as many as I can, and I will do it, and get them to Council

Bluff. . . . I’ll get you thro’ as quick as I can.”

Brother

Allen shared news from the pioneer camps.

He asked the camp to exert themselves to yoke up available teams and

prepare to leave. Forty‑ two of

the 350‑400 people immediately volunteered to go with twenty wagons,

seventeen oxen, four horses, and forty‑one cows. Sister Mary Fielding Smith, the widow of

Hyrum Smith, and her sister, also a widow of Hyrum, Mercy Fielding Thompson,

donated eighteen dollars for the company’s benefit. Even though these devoted sisters suffered from lack of food and

shelter, they stepped forward to help those even less fortunate than

themselves. Mary’s seven‑year‑old

son, Joseph F. Smith, later the sixth president of the Church, was with his

mother in this destitute camp.

The

vanguard battalion companies passed through the town of San Miguel, a large

Mexican town of about 150 homes.14 They observed a large two‑story Roman

Catholic Cathedral. While in the town,

many of the soldiers traded goods with the Mexicans. Daniel Tyler wrote that they were amused at watching the process

of milking goats. “It was generally

done by boys, who sat at the rear of animals, and the milk pail caught frequent

droppings . . . which were carefully skimmed out with the fingers. Possibly, this may in some degree account

for the extreme richness of the goat’s milk cheese.”

As they

marched on, they passed through mountains and saw some snow. They made their camp on the Pecos River near

the present‑day town of South San Ysidro. The rear companies arrived at Las Vegas, where they saw fine

gardens along with 3000 sheep, 200 goats, and numerous cattle.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 408‑09; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:92; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah

Historical Quarterly, 14:149; Ward, ed., Winter Quarters, 96;

Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

170; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 167‑68; “The Journal of

Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74; Tyler, A Concise

History of the Mormon Battalion, 164; Brown, Life of a Pioneer, 39;

“Orval M. Allen Diary,” LDS Archives; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal,”

Bagley (ed.), Pioneer Camp of the Saints

In the

morning, Brigham Young and other members of the Twelve met with Almon W.

Babbitt and discussed the affairs at Nauvoo and California. Wilford Woodruff and Orson Pratt went out

into the streets of Winter Quarters and ordained three of the men called to

serve as bishops in the settlement. The

city was taking shape. With the help of

several men, Lorenzo Dow Young, raised the walls of his house.

In the

evening the brethren heard letters read, including a thirteen‑page letter

from Elder John Taylor, written from New York to his wife before he sailed for

England. They also read a circular

written by Elder Taylor while still in the States which condemned Strangism, and

a letter written in May by passengers from the ship Brooklyn while on

the Island of Juan Fernandez. This was

the first news received of the voyage.

A son,

William Heber Pitt, was born to William and Cornelia Pitt.15

Maryanne Bruce, age thirty-six, died.

A son,

Hyrum Rich, was born to Charles C. and Sarah Rich.

A son,

Thomas Miller, was born to John and Janet Miller.16

The

battalion marched eighteen miles up the valley of Pecos until they came to the

Abbey of Pecos which was built about 250 years earlier. Henry Standage wrote, “The walls are in a

ruined state, still some of the rooms are in good repair.” Some of the buildings in the town were about

thirty feet high and contained many rooms with curious carvings. They rested at a spring nearby that “gushed”

out of the north bank of Pecos Creek, around which was silver ore. They proceeded two more miles west of the

ruins and camped for the night.

The

officers received news that General Kearny had instructed Captain Philip St.

George Cooke to take over command of the Mormon Battalion at Santa Fe. John D. Lee wrote: “This information struck Lieut Smith and Adj Dykes as well as

many others of the officers almost speechless as they had been anticipating

something very different.”

The rear

companies of the battalion left Las Vegas, traveled about twenty‑one

difficult miles, and camped about a half mile from the present‑day town

of Blanchard, New Mexico. The soldiers

complained that Lt. Oman was “unfeeling” for driving this weaker detachment so

hard.

Brother

Tarleton Lewis received permission to cross back over the river to Nauvoo in

order to obtain a yoke of cattle for his journey to the west.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 409‑10 Wilford Woodruff’s Journal,

3:92; “Diary of Lorenzo Dow Young,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 14:149;

Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

170; Jaunita Brooks, Diary of the Mormon Battalion Mission, 296‑98

Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 168‑69, 174; “The Journal of

Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74

Almon W.

Babbitt left Winter Quarters and started back for Nauvoo with a package of

letters for many of the Saints spread across Iowa. Hosea Stout went out to search for his mare. He traveled over hills and through valleys

but could not find it. He did find a

grove in a prairie that was full of walnuts.

Eliza Hall

Cook was born to Phineas and Ann Cook.

Her sister Harriet later recorded:

“On the 9th day of October another little daughter was born to them

while in a tent and during a heavy rainstorm.

They had to hold umbrellas over Mother’s bed to keep her dry. She was very sick and came so near dying,

her baby had to be taken from her and weaned at the age of three months, and

for the want of proper food and nourishment it died May 12, 1847.” Patty Sessions helped with the delivery of

this baby. She wrote: “I put Sister

Cook to bed with a daughter. Went horseback five miles.” Later, Sister Sessions baked some pies with Sister Kimball.

Patty C.

Hakes, age seventeen, died of chills and fever. She was the daughter of Weeden V. and Eliza A. Hakes. Lehi M. Vance, age twenty-seven days, died

of fever. He was the son of John and

Elizabeth Vance. Hannah Jones, wife of

Alonzo Jones, died.

As the rescue

team was organizing the starving Saints on the banks of the Mississippi River,

a wonderful miracle was experienced.

Thousands of quail descended on the camp which was an event similar to

that experienced by ancient Israel in the wilderness recorded in Exodus 16:13.

Henry

Buckwalter wrote: “So tame were they

that one could pick them right up alive.

And I assure you that they were greatly appreciated by one and all as

what few effects of this world’s goods they were in possession of were mostly

left behind in their bustle to get away from Nauvoo.”

Joseph

Fielding recorded: “They came in vast

flocks. Many came into the houses where

the Saints were, settled on the tables, and the floor and even on their laps,

so that they caught as many as they pleased.

Thus the Lord was mindful of his people.”

Mary Field

added, “They were so tame we could catch them with our hands. Some of the men made wire traps so they

could catch several at a time. We did

not have any bread and butter or any other food to eat, so we ate stewed quail

and were very thankful to get that, for we were starving although we were in a

land of plenty, because our enemies were in possession of our food.”

This

phenomenon was said to have extended some thirty or forty miles along the

river. Some later believed that the

birds became so exhausted from a long flight that they landed on boats in the

river and all along the banks.

Thomas

Bullock left this graphic account:

On the 9th

of October, several wagons with oxen having been sent by the Twelve to fetch

the poor Saints away, were drawn out in a line on the river banks, ready to

start. But hark! What noise is that?

See! The quails descend; they alight close by our little camp of twelve wagons,

run past each wagon tongue, when they arise, fly round the camp three times,

descend, and again run the gauntlet past each wagon. See the sick knock them down with sticks, and the little children

catch them alive with their hands. Some

are cooked for breakfast, while my family were seated on the wagon tongues and

ground, having a wash tub for a table.

Behold, they come again! One descends upon our teaboard, in the midst of

our cups, while we were actually round the table eating our breakfast, which a

little boy about eight years old catches alive with his hands; they rise again,

the flocks increase in number, seldom going seven rods from our camp,

continually flying around the camp, sometimes under the wagons, sometimes over,

and even into the wagons, where the poor sick Saints are lying in bed; thus

having a direct manifestation from the Most High, that although we are driven

by men, He has not forsaken us, but that His eyes are continually over us for

good.

At noon,

having caught alive about 50 and killed some 50 more, the captain [Orville M.

Allen] gave orders not to kill any more, as it was a direct manifestation and

visitation from the Lord. In the

afternoon hundreds were flying at a time.

When our camp started at 3 p.m. there could not have been less than 500

(some say there were 1500) flying around the camp. Thus I am a witness to this visitation. Some Gentiles who were in the camp marvelled greatly; even some

passengers on a steamboat going down the river looked with astonishment.

The

Council of the Twelve several months later wrote about this event to the

missionaries in England:

Tell ye

this to the nations of the Earth! Tell it to the Kings and nobles and the great

ones ‑‑ tell ye this to those who believe that God who fed the

Children of Israel in the wilderness in the days of Moses, that they may know

there is a God in the last days, and that his people are as dear to him now as

they were in those days, and that he will feed them when the house of the

oppressor is unbearable, and he is acknowledged God of the whole Earth and

every knee bows and every tongue confesses, that Jesus is the Christ.

During the

morning, a message had been sent over the river to the Nauvoo Trustees telling

them that Captain Allen was about to leave with a company of the poor. In the afternoon, provisions were brought to

the camp from the Trustees. Items such

as clothing, shoes, molasses, salt, and pork were distributed throughout the

camp. Afterwards, Orville M. Allen

started west toward Winter Quarters with a company of 157 Saints in 28 wagons.17

Thomas

Bullock wrote:

Captain

Allen called out my Wagon to take up the line of March for the West, when I

left the banks of the Mississippi, my property, Nauvoo and the Mob for ever,

and started merrily over a level prairie, amid the songs of Quails and Black

Birds, the Sun shining smilingly upon us, the cattle lowing, pleased at getting

their liberty. The Scene was

delightful, the prairie surrounded on all sides by timber. All things conspired for us to praise the

Lord.

The

company traveled three miles and then camped for the night.

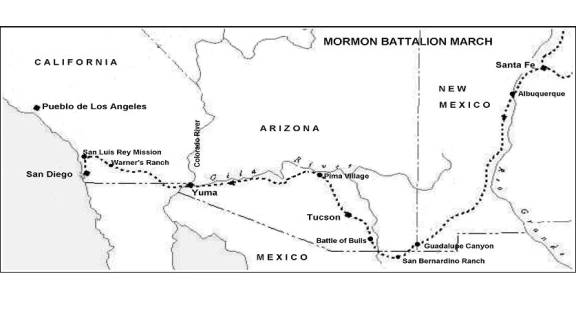

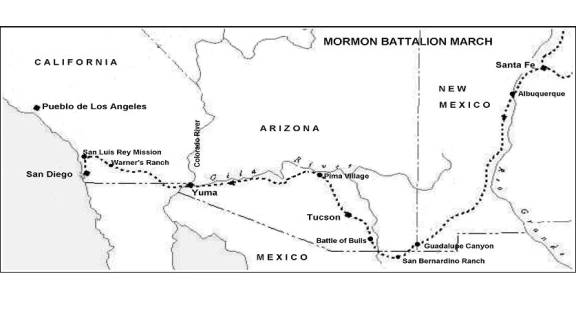

The

battalion achieved one of its important goals ‑‑ the first division

arrived in Santa Fe. In less than two

months, the Mormon Battalion had marched all the way from Fort Leavenworth, a

distance of nearly eight hundred miles.

As they

approached, General Alexander Doniphan, longtime friend of the Mormons and

commander of the post, ordered a salute of one hundred guns to be fired from

the roofs of the adobe houses in honor of the battalion. They marched in, during a storm of rain and

hail, with fixed bayonets and drawn swords to the public square. After an inspection, they made their camp,

east of the Santa Fe Cathedral.

Altogether there were about sixteen hundred men stationed in Santa Fe at

that time. Historian John Yurtinus mentioned

that one of the men from another unit wrote about the battalion: “They are well drilled, a shabby‑looking

set.”

Still on

the road toward Santa Fe, when Lieutenant Oman gave orders for the second

division of the battalion to strike their tents and march, Lieutenant Elam

Luddington of Company B refused. He had

broken his wagon the night before and wanted to repair it. Oman wanted to turn over the command of

Company B to Sergeant Hyde, but Hyde insisted on honoring Lt. Luddington’s

request to keep the company together with him.

Thus, the battalion again was divided, with a company led by Lt. Oman

and another led by Lt. Luddington. The

second division, led by Lt. Oman, traveled through the town of San Miguel and

camped after a twenty-mile march. Their

camp was located near present‑day Rowle, New Mexico.

John Steel

wrote:

We soon

went on through the great forest of cedar wood and came to San Miguel where

ladies were on top of the house, and when they saw that I had women in my wagon

they hastened down and sent their old father to invite us in. Then when the women got out of the wagon

there was such a hugging as I had never seen before, as that was their manner

of saluting. We did not stay there long

as I discovered skulking around the corrals a great number of men, and as my

team was the last and I was alone, I must hasten on. It was well I did as I was told they were planning to steal my

little girl Mary.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 410‑11, 497; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon

Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 204; Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 1846‑1852,

84; “Henry Buckwalter, autobiography,” typescript, BYU, 3‑4; Joseph

Fielding Diary in “Nauvoo Journal,” BYU Studies 19, 165‑166; Mary

Field Garner, Our Pioneer Heritage, 7:407; Roberts, Comprehensive

History of the Church, 3:136; Our Pioneer Heritage, 1:506, 8:236,

19:355; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 252‑53; Journal of Elijah

Elmer, quoted in Gibson, Journal of a Soldier, 250‑51; Journal of

Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion, 170‑71;

Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 169, 175; “The Journal of Robert S.

Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp

Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the Saints; Patty Sessions

diary in Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:62

Brigham

Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards went to administer to Eliza Ann

Peirson, who was very sick.

Most of

the brethren in the Camp of Israel went to the herd grounds where they all

worked to gather the cattle together in preparation to sending them north for

the winter. Many were still missing.

Hosea

Stout received an order from Stephen Markham to appoint men each night to stand

guard over Winter Quarters. Eight men

would be needed to fill two five‑hour shifts during which they would

guard the city against fire, accident, and from those who might try to cause

harm on the city. Brother Stout tried

in vain during the day to raise a guard for the night but so many men were away

at the herd grounds.

Jacob

Gates, James Case, and others arrived at Cutler’s Park from the Pawnee village.

Mary

Richards continued to write a letter to her missionary husband, Samuel W.

Richards, in England. She had recently

read a letter he had written to a friend and she was feeling very lonely. She wrote:

It gave me

much comfort to hear from you although I often wonder why it is that I cannot

have a letter from you as well as others.

I am sure if you thought half as much about me as I do about you, or

felt half so lonely, you could not forbear writing so long. I would just as soon you had wrote 6 letters

before you sailed, as to have waited till the last day, it would not have hurt

my feelings the least mite. But perhaps

I am finding fault without cause, you may have wrote to me. If so I ask your forgiveness and will try to

wait patiantly for the proof of your rememberance.

Thomas

Bullock wrote: “About 10 we started, on

a cold, dull morning, up a very steep hill, thro’ a Wood, which proved a

regular teazer to a many teams. The

trees begins to cast their leaves and begins to show like autumn. On the road I picked up a nice dish of

mushrooms which was sufficient for our dinner.” The company camped on the east side of Sugar Creek after

traveling about thirteen miles. In the

evening a loud crash was heard as a tree fell in the camp. Luckily, no one was hurt.

During the

day, four companies of Colonel Stearling Price’s Missouri Cavalry arrived at

Santa Fe. The battalion took great

pride in knowing that they had arrived a day before the Missouri Volunteers

even though these men had a two-day head‑start from Fort

Leavenworth. The Missouri Volunteers

were not greeted with a gun salute as had been given to the Mormon Battalion

which did not sit well with Colonel Price.

Many of

the soldiers in the battalion were able to go out into the city and become

acquainted with the customs of the people.

The town of Santa Fe was situated in a valley nearly surrounded

completely by mountains. The houses were

generally flat‑roofed adobes and the streets were crooked and

narrow. Many felt that the whole city

looked very much like an extensive brick‑yard. A large American flag made of silk flew gracefully near the fort

which was under construction. The Mexican

inhabitants had many flocks of goats and cattle.

John D.

Lee observed, “A stranger at the first glance would conclude that there was not

a room in the whole city that was fit for a white man to live in but to the

contrary, some of their rooms are well furnished inside ‑‑ floors

excepted.”

The town

was full of activity. The men found

goods that were priced very cheap. All

over town, women and girls were selling pine nuts, apples, peaches, pears,

grapes, bread, onions, boiled corn, and melons. Brother Lee was impressed to watch a team of four small burros

who were fastened together, carrying a load of wood on their backs. They were driven without bridles or lines.

The men

were very interested in watching the Mexicans.

James S. Brown recorded:

Their costume,

manners, habits, and in fact everything, were both strange and novel to us, and

of course were quite an attraction.

Many of the people looked on us with suspicion, and if it had been in

their power no doubt they would have given us a warm reception; others appeared

to be pleased, doubtless because it made trade better for them, and on that

account they seemed very friendly. They

brought into camp, for sale, many articles of food; the strongest of these red

pepper pies, the pepper‑pods as large as a teacup, and onions (savoyas)

as large as saucers, to be eaten raw like turnips.

The men

also enjoyed penuche (fudge candy) and torillas with Chile Colorado (beef in

hot sauce). Some men were very daring

in trying out new Mexican cuisine.

Abner Blackburn wrote:

On the end

of a board was something which looked good to eat. One of our crowd began to eat it, who soon found it to be stringy. The Mexican woman looked wild at him and

putting her hands to her stomach exclaimed; “Corambo Americano!” The fellow

tried to throw it up and caught hold of the end and pulled it out like a snake. We supposed it to be some kind of rat poison

as there was plenty of rats around. We

were a little careful about eating their ammunition afterwards.

There was

much gambling activity going on.

Several soldiers went on a gambling spree and were put in the guard

house. Some of the Missouri volunteers

were determined to release their fellow soldiers and broke down the guard house

in a struggle. One of the guards fired

and killed two of the volunteers.

John D.

Lee urged Captains Jefferson Hunt and Jesse Hunter to visit to paymaster. Brother Lee had been sent from Winter

Quarters to retrieve the battalion pay.

Paymaster Jeremiah Cloud agreed to pay the soldiers for one and one half

months’ service when the second division of the battalion arrived in Santa Fe.

The second

division continued their march toward Santa Fe. They marched to the Pecos Ruins where they rested and then

continued on for about two more miles.

They camped in mountains covered with pine trees and evergreens. The sick continued to openly condemn Lt.

Oman for the pace of the forced march.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 411; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:92;

Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

204; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the

Saints; Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon

Battalion, 175‑76; “Thomas Dunn Journal,” typescript, 8; Juanita

Brooks, John Doyle Lee, 101; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 170‑71,

176; “The Journal of Robert S. Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly,

4:74 Brown, Life of a Pioneer, 39; Bagley, Frontiersman: Abner

Blackburn’s Narrative, 43; Nibley, Exodus to Greatness, 253; Ward,

ed., Winter Quarters, 96

Rain

started to fall heavily at about 10 a.m. and continued into the afternoon. During that time, about two thousand cattle

from “the big herd” arrived into Winter Quarters and almost filled the entire

town. Those driving the herd were not

able to keep them on the prairie.

Wilford Woodruff described: “And

while the rain poured down in torents, I with many others had to go into the

midst of the herd & separate my cattle.

I was quite unwell with the auge but got thoroughly drenched with

water. I laboured hard in the rain

through the day.”

John

Cummings, age four, died of chills and fever.

He was the son of George and Jane Cummings. A son, Samuel B. Flake, was born to James and Agnes Love Flake.

Thomas

Bullock wrote: “We started again having a beautiful Sky over our head [and] a

delightful breeze from the West in our teeth, over a very level prairie.” They traveled on a windy road, full of

stumps, and soon arrived at the banks of the Des Moines River. They crossed the river in pouring rain. It was impossible to light a fire that

evening. At Bonaparte, a daughter,

Emily Wilson, was born to Bradley B. and Agnes Hunter Wilson.18

The

battalion members went out into the city of Santa Fe. Many of the men attended a Mass at the Catholic Church which was

a curious ceremony to them. They

marvelled at the many pictures and images that were hanging inside the

church. Violins, triangles, drums, and

other instruments were used to play beautiful religious music. Sergeant William Coray commented about the

daily Masses, “I dare say there is enough holy water administered in Santa Fe

every morning to swim an elephant.”

An express

arrived with a message from General Kearny for the Mormon Battalion. The General gave official orders that

Captain Cooke was to take over command of the battalion. He should fit the battalion with sixty days

of rations and follow General Kearny’s trail to the Pacific where they would

wait for further orders. The battalion

would then probably be taken by ship to the Bay of Monterey. Captain Cooke invited the Mormon officers of

the Battalion to meet with him. He

proposed that the sick, women and children in the battalion be sent to Pueblo

for the winter. In the spring they

would be taken, at the expense of the government, to the west where they would

rejoin their families. The officers

agreed with this proposal.

A

battalion member, Philemon C. Merrill wrote a letter to his wife. “It is hard times. I tell you, some times I think that I never can stand it on my

part. I could stand any thing on my

part, but to see my brethren suffer as they do is hard. It pains my heart to behold it.”

The second

division of the battalion marched eighteen miles through Apache Pass and camped

seven miles beyond Gold Dust Springs.

The third division started their march at 4 a.m. and ate their breakfast

at the Pecos Ruins. Robert S. Bliss

wrote, “The temple was a great curiosity.

No one knows when it was built.

It was in ruins 200 years ago & it has every appearance of an Old

Nephite City. The rooms, doors,

carvings, painting & hireoglifics were a great curiosity, the bones of

their dead also.”

Elder

Addison Pratt preached a farewell discourse on Temarie, administered the

sacrament, and baptized six people. In

the evening, he performed a marriage.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 411; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:93;

Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

204; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the

Saints; Ellsworth, The Journals of Addison Pratt, 291; Journal of

Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion, 176;

Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 171‑72, 176; Philemon C. Merrill

letter to Mrs Cyrena Merrill, LDS Church Archives; “The Journal of Robert S.

Bliss,” The Utah Historical Quarterly, 4:74; “Norton Jacob

Autobiography,” BYU, 43‑4; “William Coray Journal”

Hosea Stout

finally found his mare that had been missing for six weeks. Wilford Woodruff spent the day riding around

the lake and through the river bottoms in search of cattle. Willard Richards’ niece, Eliza Ann Peirson

died of chills and fever. She was the

daughter of William and Nancy Richards Peirson.

A son,

Samuel Bulkley, was born to Newman and Jane Draper Bulkley.19

Because of

heavy rains, the company stayed in their camp on the banks of the Des Moines

River, across from Bonaparte, Iowa. The

town contained 40-50 houses and a saw mill which was not working at the time. Thomas Bullock observed: “It appears a snug place.” Captain Allen purchased some provisions in

the town while the camp was busy washing clothes. The weather cleared and it turned out to be a pleasant day.

The second

division of the battalion arrived in Santa Fe during the afternoon, marching in

good order to music. A soldier from the

regular army wrote:

The

remainder of the Mormons came up, and when the wagons containing the women

stopped at the place, all the Mexican women near went up and shook hands with

them, apparently both rejoiced and surprised to see them. . . . I saw one very

pretty Mormon girl who seemed highly pleased at her reception in Santa Fe and

received the Mexicans with as bland a smile as they could have wished.

The third

division, led by Lt. Elam Luddington, arrived later in the evening.

Addison

Pratt was called upon to go and see a very old brother in the Church. Elder Pratt wrote:

I saw he

was verry weak and feeble. Said I, “You

are verry weak and low, and in all probability near your end,” for I saw the

lamp of life was nearly extinguished.

“Yes,” said he, “I am, and what is to become of me? I have been a

warrior and a man of blood. I have

sacrificed the lives of many of my fellow creatures.” Said I, “You did it in a

time when you was swallowed up in heathenish superstition and ignorance. You did it to revenge upon your

enemies. And Paul says, Acts 17:30 ‘The

times of this ignorance God winked at; but now commandeth all men every where

to repent.’ And when this his word came to you in the gospel of his son Jesus

Christ, you obeyed it, you have been adopted by baptism into his kingdom, and

since that, you have kept his commandments, and now your trust must be in him

whose blood is able to cleanse you from all sins. And now do not let your mind waver, but place your hope and faith

on him, and he will lead you safely through the dark valley which you are now

about to pass, to that blissful abode of eternal rest, prepared for all that

love and keep his commandments.”

A few days

later he died.

Brooks, ed., On the

Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 204; Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:93; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley,

ed., Pioneer Camp of the Saints; Ellsworth, The Journals of Addison

Pratt, 292; Yurtinus, A Ram in the Thicket, 176‑77

On this

cold day, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and their families attended the

funeral of Elder Willard Richards’ niece, Eliza Ann Peirson. A son, Isaac Cutler Kimball was born to

Heber C. and Emily Kimball. A large

number of the brethren were busy making brick which would be used for chimneys.

A wildfire

burned on the prairie to the south which destroyed six or seven tons of

hay. In the evening a large company of

men was successful in putting out the fire.

The wind had made controlling the fire difficult. Horace Whitney wrote: “The wind was so high today that my tent,

together with a number of others, was blown down, and we were not able to put

them up again until evening, when the wind ceased.”

It was

discovered that each day a few beef cattle were being stolen by their

neighbors, the Omaha Indians. Horace

Whitney explained, “They have had for some time in contemplation a grand

buffalo hunt, which they have abandoned in expectation of living and sustaining

themselves by the killing of our cattle instead.” At times, they would even try to sell the meat back to the

Saints.

In the

afternoon, Thomas Bullock went with Captain Allen over to Bonaparte to obtain

meal and beans. Brother Bullock

wrote: “Altho’ the River is wide and

shallow the Water is the most beautiful that I have seen, for the size of the

River. The bottom is solid Rock, with

loose Stones on it.”

Colonel

Philip St. George Cooke officially assumed command of the Mormon Battalion.20

Colonel Cooke later reflected on the challenge that was presented to him

with this new assignment. “It [the

battalion] was enlisted too much by families; some were too old, some feeble,

some too young; it was embarrassed by many women; it was undisciplined; it was

much worn by travelling on foot, and marching from Nauvoo, Illinois; their

clothing was very scant; there was no money to pay them, or clothing to issue;

their mules were utterly broken down.”

He

numbered the battalion at 486 men, included 60 who were invalids or unfit for

service. There were still twenty‑five

women and many children with the battalion in Santa Fe. Colonel Cooke understood that the journey

ahead would be rugged and only the healthiest men would be able to accomplish

the march. He decided to send the sick

and all the women and children (without husbands) to spend the winter in Pueblo

[Colorado]. The plan was protested by a

number of the men. John Steel

confronted the captain. He wrote that

he did not want to have his wife “left there with only a squad of sick men, I

would not stand it, and the more I talked the more angry I got until at last I

could have thrashed the ground with him.”

General Doniphan later had the order changed to allow a few husbands to

go with their wives to Pueblo.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 412; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The

Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 204; “Journal of Horace K. Whitney”;

“Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer Camp of the

Saints; Brooks, John Doyle Lee, 102; Yurtinus, A Ram in the

Thicket, 178‑89; Brown, Life of a Pioneer, 41; Nibley, Exodus

to Greatness, 255-56

The

morning was damp and rainy. Brigham

Young laid the foundation of his log house and Heber C. Kimball finished the

walls of his house.21 Wilford Woodruff’s division spent most of

the day building a bridge over Turkey Creek.

Elder Woodruff also worked to mend his tent.

Several

brethren arrived from Nauvoo after a three-week trip. Horace Whitney wrote of their report:

It appears

by their statements that the mob have been pretty busy, plundering houses,

ripping open feather beds and scattering the contents in the streets. They have also defaced the Temple

considerably, inside and out, such as knocking horns from the oxen in the font,

running about the streets and imitating the blowing of horns with them and

doing other acts of sacriledge too numerous to mention. . . . The mob have torn

down the altars and pulpits in the Temple and converted that edifice into a

meat market.

Hosea

Stout crossed over the river at the new ferry crossing, traveled to Henry W.

Miller’s camp and then on to his mother‑in‑law’s camp. The traveling was very difficult over hills

and down ravines. He found his family

doing well and settled next to many of his old neighbors from Nauvoo. Several of the brethren were away on a bee

hunt.

A

daughter, Amanda Jane Rogers, was born to Ann Doolittle Rogers.22

The

company attempted to attack a steep hill near Bonaparte that so many other

companies had had great difficulty climbing during the past months. It was no different for the poor camp. Thomas Bullock wrote:

We started

on the side of a hill, sideways, and slipping almost every yard, thro’ a wood

among stumps and logs. It had commenced

raining during dinner and continued all the journey, which, with the dreadful

road itself, made it most decidedly the worst travelling we have yet had, and

may the Lord preserve us from worse; after much difficulty we got to the top of

the hill where we halted, until every one of the teams got up without accident.

They

camped after six miles. The camp had

been having trouble with pigs coming into their campground. “This is the first night that we have been

free from pigs, and that we had a little peace, not being troubled with the

brutes.”

A son,

Joseph Hyrum Armstrong, was born to John and Mary Kirkbride Armstrong.23

John M.

Bernhisel wrote a letter to Brigham Young while on the steamboat, Fortune. He was on the way to visit towns to seek

food and clothing for the destitute Saints.

He reported that there were only about 8‑10 non‑resident

members of the mob left in Nauvoo.

However, they still did not permit any of the brethren to enter the

city. A mob meeting was scheduled to be

held the following week in Carthage. He

felt that the mob would decide to withdraw from the city because public opinion

was against them all over the country.

He also

wrote:

There is

still quite a number of our people encamped along the shore for about two miles

above Montrose, some have tents, some have quilts or blankets put up for a

shelter, some lodge in wagons, and some few have nothing but a bowery made of

brush. The health of the people is

better than it has been, but still there is considerable sickness among them,

but the most of it is chills and fever.

Colonel

Cooke appointed Captain James Brown to lead the second sick detachment to

Pueblo, about 180 miles to the north.

Private James S. Brown described how the sick men were selected.

We were

drawn up in line, and the officers and Dr. Sanderson inspected the whole

command. The doctor scrutinized every

one of us, and when he said a man was not able to go, his name was added to

[the] detachment, whether the man liked it or not; and when the doctor said a

man could make the trip, that settled the matter. The operation was much like a . . . butcher separating the lean

from the fat sheep.

The

detachment consisted of 86 men, 20 women, and many children.

At first,

all the men assigned to the sick detachment were going to be discharged from

the battalion and would lose their pay.

However, after an appeal to General Doniphan the men were told that they

would not be discharged after all, but be put into “detached service.”

Colonel

Cooke made a very controversial change in the battalion leadership. He appointed Lieutenant A.J. Smith as the

battalion quartermaster in place of Quartermaster Samuel Gully. Levi Hancock and John D. Lee started a

petition requesting Brother Gully to be reinstated. The petition was presented to General Doniphan who agreed with the

petition but he explained that he could not help. John D. Lee then counseled Samuel Gully to resign from the army

in protest and return with him to Council Bluffs.

A fandago24 was put on by the Mexicans and the

Missourians. Most of the members of the

battalion attended at a cost of two dollars per person. John D. Lee refused to go, feeling that it

would be a violation of his covenants if he associated with unbelievers. He also disliking seeing about one thousand

dollars spent foolishly when it could be sent back to help the poor.

William

Coray wrote:

The

officers were requested to attend a party and bring their ladies with

them. I was against the operation but I

was finally persuaded to go for curiosity.

Our accommodations were poor, and the whole affair sickened me. I saw them dance their waltz or what they

called Rovenas. Their music was

tolerable, but the ill manners of the femailes disgusted me. . . . I thought I

would stick it out till supper but had I known before what I knew afterwards

the supper would have been no object as it proved to be a grab game all the way

round, and the man that waited for manners lost his supper.

James

Emmett, Joseph Holbrook, and William Matthews left Ponca for an exploring

expedition. They wished to explore a

route to Fort Laramie.25

Elder

Parley P. Pratt and fellow missionaries, Samuel W. Richards, Franklin D.

Richards, and Moses Martin arrived in Liverpool, England after a twenty-two-day

voyage. They were in good health and

spirits. Soon they found Elders Orson

Hyde and John Taylor, and were kindly received by the Saints.

Watson, ed., Manuscript

History of Brigham Young, 412, 433, 487‑88; Hartley, My Best for

the Kingdom, 221; Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, 346; Wilford

Woodruff’s Journal, 3:93; Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary

of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861, 204‑05; Brown, Life of a Pioneer,

41; Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

176; Woman’s Exponent 13:139; Brooks, Mormon Battalion Mission: John D. Lee, 204‑05 Nibley, Exodus

to Greatness, 256‑57; Ricketts, Melissa’s Journey with the Mormon

Battalion, 36‑7; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer

Camp of the Saints

Wilford

Woodruff experienced what he referred to as “one of the most painful and

serious misfortunes of my life.” As

Elder Woodruff was working on his house, he traveled to the bluffs to cut some

shingle timbers for his roof. He

recorded:

While

felling the third tree, I stepped back of it some eight feet, where I thought I

was entirely out of danger. There was,

however, a crook in the tree, which, when the tree fell, struck a knoll and

caused the tree to bound endwise back of the stump. As it bounded backwards, the butt end of the tree hit me in the

breast, and knocked me back and above the ground several feet, against a

standing oak. The falling tree followed

me in its bounds and severely crushed me against the standing tree. I fell to the ground, alighting upon my

feet. My left thigh and hip were badly

bruised, also my left arm; my breast bone and three ribs on my left side were

broken. I was bruised about my lungs,

vitals and left side in a serious manner.

After the

accident, Elder Woodruff painfully rode his horse for almost three miles on a

very rough road.

My breast

and vitals were so badly injured that at each step of the horse the pain went

through me like an arrow. I continued

on horseback until I arrived at Turkey Creek, on the north side of Winter

Quarters. I was then exhausted, and was

taken off the horse and carried in a chair to my wagon. . . . I was met in the

street by Presidents Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Willard Richards, and

others, who assisted in carrying me to [my] wagon. Before placing me upon my bed they laid hands upon me, and in the

name of the Lord rebuked the pain and distress, and said that I should live,

and not die.26

Eliza

Partridge Lyman recorded in her journal:

“We went into our log house, the first house my three-month-old baby has

ever been in.”

As Hosea

Stout was searching for oxen that he had lost many weeks earlier, he visited

the former headquarters of the Camp of Israel which had been located on

Mosquito Creek.27 He wrote, “This country presented to me a

dreary appearance and especially my old tenting ground on Hydes ridge. I passed down by Taylor’s camp which was now

but a deserted point all dreary & lonesome.”

Brother

Stout continued on down to Council Point, near the river. He spent the evening with George and Joseph

Herring, Indians, who were members of the church. He had a wonderful evening with them and was treated with much

kindness.

The

company did not travel on this cold and windy day. They waited for Brother Fisher to catch up and also sent men back

to Bonaparte to hunt for stray cattle.

They returned in the evening with three teams.

The

officers in the battalion started to receive their pay. Colonel Cooke issued the official orders for

the sick detachment.

Agreeable

to instructions from the Colonel commanding, Capt. Jas. Brown will take command of the men reported

by the assistant surgeon as incapable, from sickness and debility, of

undertaking the present march to California.

The Lieutenant‑Colonel, commanding, deems that the laundresses on

this march will be accompanied by much suffering and would be a great

encumbrance to the expedition; and as nearly all are desirous of accompanying

the detachment of invalids which will winter near the source of the Arkansas

River, it is ordered that all be attached to Captain Brown’s party.

The

detachment will consist of Captain James Brown, three sergeants, two corporals,

sixteen privates of company C; First Lieutenant E. Luddington and ten privates

of Company B; one sergeant and corporal and twenty‑eight privates of

Company D; and one sergeant and ten privates of Company E., and four laundresses

from each company. Captain Brown will,

without delay, require the necessary transportation and draw rations for twenty‑one

days. Captain Brown will march on the

17th inst. He will be furnished with a

descriptive list of the detachment. He

will take with him and give receipts for a full portion of camp equipments.

The

commanding officer calls the particular attention of company commanders to the

necessity of reducing the baggage as much as possible; transportation is

deficient. The road most practicable is

of deep sand and how soon we shall have to abandon the wagons it is impossible

now to ascertain. Skillets and ovens

cannot be taken, and but one camp kettle to a mess of not less than ten men.

Company

commanders will make their requisitions on the Assistant Quartermaster, Captain

W. M. D. McKissock, for mules and wagons, provision bags, pack saddle complete,

and such other articles as are necessary for the outfit.

An

editorial appeared in the Millennial Star announcing the mission of

Orson Hyde, John Taylor and Parley P. Pratt in England.

During last

winter, the council of the church in America under guidance of the Holy Spirit,

deemed it necessary to send to you a number of fellow laborers in the gospel. .

. . Since the above arrangements were made, and in some measure carried into

effect, it hath pleased the Lord to direct the council by his Spirit to send

unto you, in addition, a deputation of three of their own number, with

instructions to regulate and set in order the various departments of the

church.

Nibley, Faith

Promoting Stories, 20‑22; Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 3:93;

Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier, The Diary of Hosea Stout 1844‑1861,

205; Journal of Henry Standage in Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion,

176; Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion, 166‑67; Roberts, Comprehensive History of the

Church, 3:123; “Thomas Bullock Poor Camp Journal” in Bagley, ed., Pioneer

Camp of the Saints; Amasa Mason Lyman, Pioneer, 157

The

weather was chilly. The Council wrote a

letter to Indian Agent, Robert B. Mitchell at Sarpy’s Point, asking permission

to use the government mill to saw boards for the construction of the Winter

Quarters flouring mill. Most of the

brethren in the city continued to work hard building houses. Horace K. Whitney had completed enough of

the roof on his house that his family was able to move into it. They shared the house with several others. He wrote, “We cleared out the inside of it

and the family moved into it in the evening.

Brother K took two of his tents down and spread them over the roof.”

A

daughter, Caroline Rocealy Hunter, was born to Edward and Laura Hunter. Patty Session helped with the delivery.28

Sarah A.

Coventon, age nine months, died of chills and fever. She was the daughter of Robert and Elizabeth Coventon.

Hosea

Stout traveled to Sarpy’s Point and wrote, “there was not much going on because

of the cold. There was many large

companies of Indians there waiting for their annual payment.”

Sister

Joan Campbell died during the night, a few hours after giving birth to a

stillborn child. When the mob attacked

Nauvoo, she had been in good health.

But after being forced to leave the city, her health became poor because

of the exposure to the wet and cold weather.

The company felt that she had died a martyr’s death. Captain Allen sent

men to Bonaparte to get wood to make Sister Campbell’s coffin. It was constructed and she was buried that

day.

Members of

the camp were detained from moving on because a constable from Van Buren County

put a lien on a yoke of cattle because of a supposed debt of eight dollars owed

by one of the members of the camp. At 8

p.m., snow flurries were seen, but melted as they hit the ground.

One of the

Nauvoo Trustees, Joseph Heywood wrote a letter to Brigham Young from what he

called, “Hell Town, formerly Nauvoo.”

He wrote about his concern for the graves of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. The location of the graves was a carefully

guarded secret. Brother Heywood

believed that a Mr. Van Tuyl, who was Emma Smith’s renter, had learned the

location of the graves from Emma.29 Brother Heywood asked for Brigham Young’s

permission to remove the bodies to another location.30

During the

night, someone broke into Doctor Sanderson’s trunk and stole his gold watch

valued at $300. Also stolen was Pilot