In 2004, at the start of my first 50-mile race, I listened to a runner giving advice to our small group of early starters about pace. This runner was trying to finish his 50th ultra in 50 states and he sported the bib number 50. Clearly he was experienced. He advised us to use a run/walk strategy – running for a set distance and then taking scheduled walks. We started and ran all together but after a mile all the others slowed down to walk. I just couldn’t do it. I pushed on and was soon far ahead of everyone. I wondered if I was doing it wrong. Later most of this group took a wrong turn, so I was glad I didn’t stick with them. But I was left wondering what the right pacing strategy is for an ultra.

One of the best places to turn for advice is ultrarunning pioneer, David Horton. “When the runners line up for the start of the race, get near the back of the pack. DO NOT get near the front; if you do you’ll pay dearly sooner or later. You will start out too fast even though it feels very easy. . . . When should you start walking in the race? If you wait until you feel like you need to walk, you’ve waited too long. You should start walking from the start, when you hit your first hill. (Horton, “Ultimate Running Experience: Completing Your First Ultra-Marathon.”)

This advice is probably very good, especially for the first ultra, but I have to admit that I’ve never followed it in all for my nearly 100 ultras. Well, one year when I was at the start of Rocky Raccoon 100, I was messing around with my stuff and when I looked up, everyone was already gone, so I certainly did start at the back of the pack. But I then had “fun” during the first few miles trying to pass several hundred runners on dark trails.

Another ultrarunning expert, Marshall Ulrich, gives this advice: “I recommend starting out at about an 80 percent intensity level. Trust me, the excitement of the start and all of the other runners around you will force you to run at least this fast. Resist the impulse to run even faster to keep up with the pack, as all you will do is burn yourself out early! Keep your pace at no more than 80 percent for the first few miles of the race. You should feel like you are moving at a comfortable pace, capable of more.” (Ultrich, “Pace Yourself for Ultrarunning Training and Racing.”)

This approach is closer to what I adhere to if I’m trying to compete and seek a good finishing time. I’ve never been an elite ultrarunner and never will be, so it is better to turn to one of the elites for advice if you are in it to win it. But I always strive for a strong showing and enjoy running near the front of the mid-pack.

For my first year of running ultras, my focus was only on finishing, but by my seventh start, I was in it to truly race. I came away surprised and pleased that I was able to push the pace well and finish in the top 20 among 90 starters. For 100-milers, I generally start pretty fast, near the front, and run the early miles at about an 80 percent intensity level. As an old guy, going out at that pace, I breathe pretty hard for the first 15 miles or so and then back off to a longer sustainable pace.

Why do I go out pretty fast rather than slow? One reason is mental. If I would start in the back with the slower runners, I would mentally get comfortable with the pace and fool myself into thinking that I’m moving pretty fast because I’m keeping up with those around me. I would get lazy and before you know it, I’m miles behind those near the front. I tend to excel if I can be pushed by those around me at a more aggressive pace as long as I never red-line.

Some races when I’m feeling great and have trained well, I can keep up that faster pace for longer. Being toward the front further motivates me and helps push me ahead. If I was toward the back, I would wonder if I lost precious time. This sounds like a recipe for crashing and burning. We’ve all seen the young rookie runner who starts very fast and by mile 50 is collapsed in a chair, done. To me, it is a balance that can be found through experience.

As I am running in the early stages of a 100-miler, I try to always keep in mind these thoughts:

- The real race starts at mile 60. Don’t try chasing everyone in sight.

- Most of these runners around me who are pushing so hard in the morning will be walking by sunset.

- Don’t get lazy. Compete.

The real race starts at mile 60.

While I like to start rather fast, I keep this in mind to hold myself back just enough. I chuckle as I watch runners who I am catching up to during the first half of the race, look behind, worried about me catching up to them. There will also always be that runner who you are trying to pass that kicks it into gear just because you are there. It is fine to be motivated, but I don’t fret about my overall position in the race before mile 60 as long as I’ve been running my best.

My goal for mile 60 is being able to run relatively fast while others are starting to walk longer stretches. If I’ve held back just enough, I know that for me, something happens around mile 60, and I frequently start feeling fantastic. This high point usually corresponds with cooler evening temperatures and also my joy in running during the night. So, I try kicking it into gear. I know that I’m having a good race if I can run up mild hills fast after mile 60 while others are walking them.

If things are working well, after mile 60, I can still start climbing the standings dramatically. At Cascade Crest at about the 55-mile mark is a long six-mile climb up to Keechelus Ridge. For me, it is close to midnight and I look forward each year to be able to really run up that hill fast. I always pass at least a dozen walkers and then I am energized for the next long fast downhill. If I’ve managed my pace well during the first half of the race, I’ll be able to find speed in the second half. But I don’t go as far to purposely run slowly near the start.

But some races I just go for it. At the 2010 Tahoe Rim 100, I found myself in 2nd place overall at mile 11. At the aid station at that point a lady saw me in a big hurry to fill up my bottles and eat. She said something about quit trying to rush, that 100 miles was a long way. At first my thought was, “but this is a race!” But she was right. I reminded myself that the real race starts at mile 60. In 2011 at Buffalo 100, a few miles into the race I was running with Karl Meltzer. I knew that was wrong but I hung closely to the front runners for a few more miles and later backed off. I finished well that year, in 3rd place and set my 100-mile race PR at 20:27. My fast start did not damage my overall race.

Runners pushing too hard in the morning will be walking by sunset

The Bighorn 100 course is an interesting case for me. This course starts with a mild climb for the first few miles which I can run fast and I usually stick with the second pack of runners. But after that is a monster climb. I hang on for the first 1,000 feet or so but then back off and am content to let others pass. I watch them push hard but I don’t fret. I make sure I’m not going at max, closer to that 80% effort. What I keep telling myself during this crazy climb is, “Half of these people will be out of gas and walking by mile 30.” One year I even reached to the top of that monster climb at the same time as David Horton, both of us pushing pretty hard but not maxing out.

At Bighorn, starting at mile 30 is a very long 18-mile climb. My goal is to run most of that 18 miles while others are walking. I’ll even run uphill portions fast and recover somewhat on the flat portions so I can run the next uphill. I love the challenge and overall the pace is faster than walking the hills and running the flats. Yes, that seems backwards, but it works for me.

What about a flat course? You hear many cautions about resisting the temptation to run fast on a flat course. I’ve ignored that advice on flat courses because of my preparation. If I have flat races coming up, I make sure I train very hard doing long fast training runs on the flat lands. If my legs can handle it, why not run fast during the race? With a very fast and flat course like Pony Express Trail 100, I have usually run the first 26 like a slowish marathon, reaching that point in a little under four hours, with very little walking up to that point. A fast start like that hasn’t appeared to damage my ability later on in the race. I’ve observed mountain 100 veterans try to do the same thing without the training investment on the flats. Many of them do crash and burn.

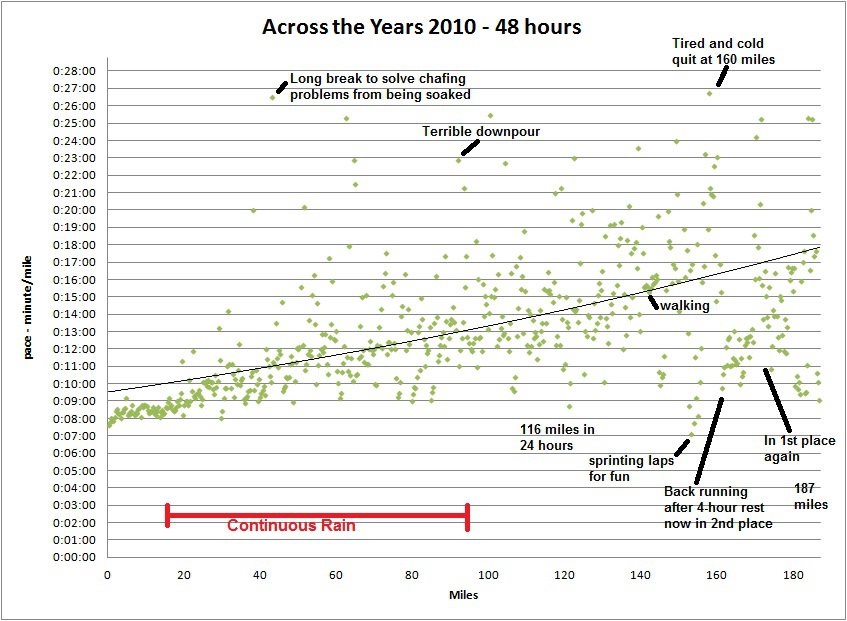

At Across the Years 48-hour, I’ve set all my ultra distance PRs by going out fast and then able to make it well beyond 100 miles without crashing. The scatter chart shows my mile-pace for each 0.5K lap for an entire 187 miles. I started fast at 8:00 pace but obviously my pace degraded over time, especially as you add in sleep deprivation. But notice the very fast pace laps very late in the race between 150 miles to the finish. In fact my fastest lap was a nearly 7:00-minute-mile lap around mile 150. With my fast start I reached the marathon point at 3:50, the 50K mark at 4:38, 50 miles at 8:07, 100K at 10:49, and 100 miles at 19:46, then ran 87 more miles.

Don’t get lazy, compete

To keep my pace up, I have to keep reminding myself not to be lazy. It is so easy to slow down just to feel more comfortable, losing focus on the pace needed to reach my goals. But there will usually be unforeseen problems that will appear due to mistakes or some bad luck.

When things go wrong

Eventually in all of my 100-mile races something goes wrong. Is my pace to blame? One of the big dangers of pushing too hard is causing the stomach to go south and then stop functioning. When the stomach revolts, it slows down your pace. When you try to push harder, the stomach fights back. Other things that can destroy your pace are dehydration, low carbohydrates, blisters, sore muscles, and other problems. It takes experience to know how to bounce back.

During 2011, I finished ten 100-milers, but it was a rough year for me. Continually at night during my 100-milers, my stomach was shut down, stop processing food, and force me to slow my pace. During Bighorn 100 it lasted all night and was pretty much torture. What was to blame? Pace? Dehydration? Electrolytes? Carbohydrates? Age? It took me most of the year to figure things out. The cause: Altitude and body temperature. During the higher altitude races, I would get chilled during the night and my body would transfer my blood flow away from my stomach. It wasn’t getting enough oxygen and would just shut down. Deeper breathing, a slower pace, or dropping to lower altitude would help. The solution now is better altitude training and making sure I am dressed warmly enough at night. It was a pretty simple solution and once understood, my pace in future races improved.

When things go wrong for long hours which cause a slower pace, once I pull out of it, I discover that I feel rested and have a ton of energy. That is then the time to salvage the race and run like crazy to the finish.

Other approaches

Will other approaches work? Certainly, it depends on what works best for you. Take the case of Matt Watts of Colorado. Matt keeps a nice steady pace throughout his 100-milers. In my early years, despite my faster starts, I could always count on Matt catching up by mile 70 because he runs so steady and is in and out of aid stations in just a minute. I knew what his normal pace was because we had run many miles with each other. In many races I would think, “OK, Matt is probably about six miles behind now but moving steady. I’m now moving slower than he is, I better pick it up.” One year when Matt ran the Pony Express Trail 100, a few miles into the race, he was pulling up the rear with no one in sight. He wasn’t worried, and he had the last laugh finishing in 3rd place that year, passing nearly everyone, and he almost caught me too.

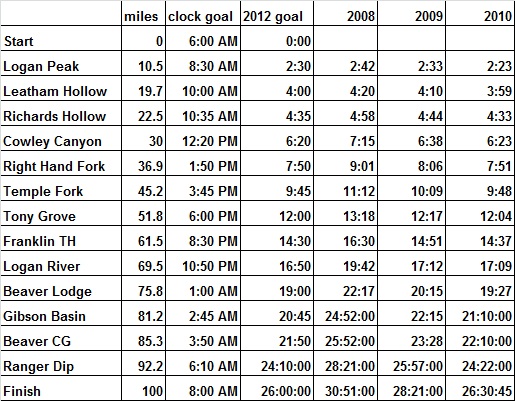

The pacing chart

In the 2009 Bear 100, at mile 20, a friend who would pace me later on was helping at the aid station. I told him to expect me at the 4:10 mark. I showed up within one minute of that pace. The next year, another friend who was managing that station knew that I was planning on arriving at 4:00. He laughed when I showed up exactly as predicted. I joked that I had been hiding behind a tree waiting until the precise moment. (Actually I would have arrived sooner but I took a bad fall with just a half mile to go). I’ve become very good at predicting my pace. How do I do it?

Before each race I construct a pacing chart. I study the course, where the climbs are, how technical the trails are and then predict and set an aggressive goal to reach each aid station. I take into account the likely mile-pace at that point, factor in that I start rather fast, and make sure I add in some time for aid station stops. If I’ve run the course before, I include the checkpoint times in past year so I can gauge how I’m doing.

Below was my pace chart for the 2012 Bear. Using this chart is another tool to motivate me. In 2008, I had some bad foot problems after mile 50 so my race fell apart. In those cases, I stop referring to the pace chart and just do my best to hold on. But if my race is going well, this pace chart is a better motivator that a pacer.

I’ve become pretty proficient at developing these charts and a few times have even developed them for other runners once I understand well their abilities. One danger is setting goals too low. I make sure I’m never content just to reach my marks. If I have a good race, I should be exceeding them.

The pace chart is also very handy to plan where to put my drop bags including my flashlight and night clothes. Knowing that I need to reach these points before dark is another motivator. In recent years I’ve also used a GPS watch to help manage my pace. In the early stages of a race it doesn’t help as much because I’m pushing hard and don’t need to push any faster. But in the later stages of a race it can help me keep my pace up to the levels it should be at. There is so many times when it feels like I’m running a 10:00 pace late in the race feeling good, but then I see that I’m actually running closer to 13:00 or 14:00. In those cases the watch can give me a kick in the pants to work harder.

With each 100, using my pacing charts, I usually have a clear, starting game plan for the first 25-50 miles. After that, I know that I have to adapt my pace to the circumstances presented to me. For example, when I run Wasatch Front 100, I push the rolling first three miles pretty hard and then fall in line with a fairly aggressive group who help pull me to the top of Chinscraper. From there, I back off the pace until the long downhill to Francis aid station where I run very fast if the legs feel good. At Tahoe Rim, I want to run nearly every step of first eleven miles to Tunnel Creek. That means a bunch of uphill running and some blistering fast downhill on the switchbacks into Tunnel Creek. I want to arrive there fast because the next section gets hotter the later in the morning that you go through it. All five years there, my starting game plan and worked great.

Having a good strategy for your pace is important in running ultras. But remember that everybody is different. You need to figure out what works best for you.