With recent public cases of ultrarunners being disqualified for cutting courses, there has been many shocked and angry discussions on social media about the topic. I’ve had deep feelings and thoughts on this topic, as I was directly impacted by one of these cases for nearly three years. I’m ready to share some of these thoughts. First, you must understand that cheating in our sport has been happening for decades. Many of us have just ignored it. Some race directors have very quietly disqualified runners caught cutting courses, letting them continue their practices at other races. A few courageous runners and race directors have refused to let these cheaters corrupt ultrarunning competition and have taken the hard road to confront the problem head on.

Cheating in the 1980s

Cheating reared its ugly head in ultrarunning in the early 1980s. In 1980 an elite 100-mile runner was disqualified for cutting the Metropolitan 50 course in Central Park, in New York City. Allegations were raised by witnesses seeing him cut courses at other races. It was suspected that he had been cheating races for years by cutting courses, skipping loops at night but still getting them recorded, and by other means. This runner’s cheating ways were made public and three years later he took revenge on his primary accuser by assaulting him during another 50-mile race in Central Park. The enraged person came onto the course around mile 9, chased the runner, screaming verbal abuse, and tried to trip the runner multiple times. When that didn’t work he socked the runner hard in the collar bone. The runner went on to finish in 6:14.

Cheating reared its ugly head in ultrarunning in the early 1980s. In 1980 an elite 100-mile runner was disqualified for cutting the Metropolitan 50 course in Central Park, in New York City. Allegations were raised by witnesses seeing him cut courses at other races. It was suspected that he had been cheating races for years by cutting courses, skipping loops at night but still getting them recorded, and by other means. This runner’s cheating ways were made public and three years later he took revenge on his primary accuser by assaulting him during another 50-mile race in Central Park. The enraged person came onto the course around mile 9, chased the runner, screaming verbal abuse, and tried to trip the runner multiple times. When that didn’t work he socked the runner hard in the collar bone. The runner went on to finish in 6:14.

Another runner in the early ‘80s seeking a record, brought their own person to record laps at a track ultra. The race director discovered that the runner’s laps were being inflated and disqualified the runner. Also during that time a runner was caught cheating, taking rides during the famed Westfield Sydney to Melbourne race in Australia.

In 1985 a runner was disqualified for clocking unbelievable six-mile laps at Birmingham 50, including a late in the race, averaging 5:32 pace. The runner firmly denied cheating but the data didn’t add up. With that lap pace, he should have passed about thirty runners going at a noticeble sprint pace. Not one runner in the field saw him pass them on that lap.

Be aware that it happens

Running legend, Gary Cantrell (of Barkley fame) wrote in 1985 that cheaters did exist in the sport. They “arrived [to races] well prepared to cheat. With small fields and sprawling courses, most ultras are easy prey for those willing to sacrifice self-respect for the respect of others. No matter how insignificant our sport is, some motivation exists for people to cheat. We know because it happens. For some, the hunger for success can be satisfied only by records and wins. For a few of those, the hunger is satisfied no matter how the result is achieved. As painful as it is, race directors must now acknowledge the possibility and make plans to catch cheaters.” (Ultrarunning Magazine, May 1985, 27).

Ultrarunning historian and Hall of Famer, Nick Marshall, observed in 1981, “Cheating espisodes are the lowlights of the sport. . . . Race Directors must always be vigilant to the possibility of cheating. There’s a tendency for organizers to avoid the subject, or even pretend it can’t happen, simply because it is such a messy area to deal with. Nevertheless, it does happen on occasion and it should be faced squarely.” (Marshall, 1980 Ultradistance Summary, 40)

The fraudulent runner

Cantrell described another type of cheater in 1985 that had plagued the ultrarunning world – the fraudulent runner. This type of runner doesn’t steal victories or destroy course records like those who have recently been disqualified at races, but they step forward to claim an undeserved spotlight for gain, disrespecting the entire sport.

Fraudulent self-promotion runners became part of the sport in the 1980s and this practice would be repeated in the decades to come. Some runners would claim to be the best in the sport, invent various solo stunt running events without oversight, achieve invented “world records,” and then use it for gain and fame even though they never truly competed with the best in the sport.

One example was Stan Cottrell who was featured in a 1981 issue of Runner’s World who claimed to be a world-class “ultramarathoner” without running in any ultra-distance races. In 1979 he claimed that he set a 24-hour world record of 167 mile in a solo run and tried to get it listed in the Guinness Book of World Records but was rejected. In 1980 he claimed to have run across America in a record 48 days setting the fastest known time at that point. The attention he received disturbed many in the sport who saw through the exaggerations and misstatements. Over the years his claims and similar assertions by others taught the sport to be cautious of claims by those who demonstrated strong motives for fame and gain.

In 2016 the Georgia Supreme Court ruled against Cottrell who sued five people for defamation over comments on the Internet accusing him of being a “scam artist.” Over the years, Stan did use his fame for a lot of good will with his “friendship” runs, but that didn’t make up for all the false claims that runners of his time detected. Since the 1980s there have been others who followed in Stan’s footsteps claiming all sorts of invented ultrarunning “world records” to further their brand and businesses.

The course-cutter

But Gary Cantrell wisely pointed out in 1985 that the course-cutter cheater was the most insidious of all cheaters because we don’t really know who they are. We don’t know how many there are and won’t know unless we all take ownership for the integrity of our sport. Thirty years later as the number of ultras have increased dramatically, new race directors have been oblivious that cheating is happening. We have become overly trusting and in many cases have looked the other way or disbelieved that cheating was happening. Courses have been designed all over the sport that can be easily cheated and cheaters seek out these kind of courses. In the world of self-promoting social media, these cheaters do what Cantrell explained in 1985: They “sacrifice self-respect for the respect of others.” Some race directors have taken good precautions to chip runners and collect data, but very few of these race directors take the time to analyze the resulting data to detect obvious anomalies. Some think that chipping runners and placing mid-course timing mats will scare away the cheater. It does not.

Kelly Agnew was my friend. (In January, 2018, articles were published all over the world about his cheating.) I deeply respected his abilities and kindness to me until in 2015 when I detected that he significantly cut a course in a race that we were both running. I was shocked, saddened and couldn’t understand why. I tried to disbelieve it. But when I detected it at another race, witnessed it at a third race, and then videoed him cheating a lap at a fourth race, I knew the truth without a doubt. Agnew was awarded the win in three of these races, and in one of them, I finished in second place. I would go home from those races with a discouraging, lonely feeling because I was pretty sure that I was the only one who had figured out what he was doing and wondered what I should do. On return home I would read his race reports that received undeserved adoration from so many of my friends. I couldn’t just look the other way because of the numerous undeserved wins and course records. I won’t get into the details of what I did after that, but I worked closely with multiple race directors who also struggled with what to do. I learned a lot from this experience. He was finally caught by one of these race directors, clocking laps he didn’t run and disqualified from Across the Years 24-hours on December 31, 2017, and then retroactively disqualified from an 22 other races, including an astonishing 13 cheated wins. He has been suspected of cheating in an additional 15 races.

I learned that many other people knew that Agnew’s cheated at least one race, but for years did nothing or understandably didn’t know what to do. In one case a race even quietly disqualified him, but still let him run their race a few years later. At another race, a runner and pacer said they saw him cheat, taking a ride to skip many miles. The pacer was furious with him and confronted him at the finish, but they decided that they would drop it, that he would have to live with his dishonesty. At another race, each year Agnew’s times were missing from critical checkpoints but the race staff apparently never took the care to follow up on a pattern of misses. At a different race, several other runners said they noticed that he would disappear at night from a loop course, never pass them, but be way ahead when morning came. But they pushed away the possibility that someone would so blatantly cheat. At another race, runners were puzzled when they seemed to only see Agnew around the start/finish area of a loop race. Another runner was puzzled that he was seen coming out of the woods with his light off. At another race with a complex course, a runner observed that he skipped a loop section. These runners did not put “two-and-two” together until his disqualifications became public in 2018.

It continues to happen

Serious cheating is still happening. Agnew is not the only one. In January Mark Robson was disqualified finishing fifth in a 100K in Australia by using similar tactics as Agnew, “hiding in bushes, and taking short cuts.” It is believed that he had only run about 70K instead of 100K. He had been previously banned in 2014 from Australian triathlons for cheating but just moved on to other venues to continue his tactics. Very recently, in February, Patrick Wills was disqualified after finishing third at Rocky Raccoon 100 in Texas. He missed out-and-back checkpoints and clocked unbelievable lap times for the second half of the race when the course was sloppy with mud. Both of these race directors took the time to check their race data and were bold enough to take action.

Competitive runners can easily detect this kind of cheating. You should always keep track of the runners around you. On loop courses don’t just look at your lap count but notice the lap counts of runners near you. We don’t want everyone to become overly paranoid and make false reports, but the way some of these cheats are caught is simply by watching and noticing, and watching some more.

Race Directors

Sadly, some race directors just don’t care that much. They are in it to get as many registrations as they can. They don’t want to deal with confrontation. Avoid running in those races. If the race director has not published the safeguards that they use, ask what they do to ensure a fair race. Happily, most race directors will take actions now that this problem has become public. Timing areas are being safeguarded more. Runners are pointing out to race directors areas of their course that can easily be cut by cheaters. More course marshalls are being placed. More race directors are analyzing their data. Cheatable courses are being redesigned. Game cameras are being used in areas that course-cutters would likely try to use. Cheaters have been put on notice, most people are watching.

Race Directors should make it clear to registered runners that course-cutting will not be tolerated and safeguards are in place to ensure that. When the Pulse Endurance Run emailed a clear message to their runners, Agnew quickly cancelled plans to run there.

These course-cutting cheaters plan ahead. They seek out cheatable courses and prey on naïve race directors. They strategically plan how they can cheat. They never publish their GPX tracks for their races.

What should be done about past records, wins, and accomplishments by a serial cheater? In the early 1980s, Nick Marshall, the keeper of ultrarunning statistics for that time, took the bold move to expunge a known cheater’s results from Nick’s historical statistics. He even refused to publish any new finishes by this runner. Nick was highly criticized by some for this action. In 2018, I think an even better practice is being used by ultrasignup. Instead of making results only disappear, DQs are highlighted in the runner’s results and they are removed from the races’ finisher lists and course bests. I wish more races would look at their past race data and take action for these runners.

“Outing” these course-cutting cheaters isn’t needed in all cases, but remember, for a serial cheater, a quiet DQ does nothing but emboldens them to continue. In all cases, vigorous social media shaming isn’t appropriate. If runners know that a race director will look for course-cutters and DQ them, it will deter this behavior.

Forgiveness is desirable and possible. When a course-cutting cheater is caught, I believe they should be banned from races depending on the severity. Shaming in inappropriate. But they should realize that if they came forward, apologized, returned awards, and answered questions, that most people will find forgiveness eventually in their hearts. The serial course-cutter of the 1980s was encouraged to write a letter of apology to Ultrarunning Magazine with a chance to “start over.” But no apology ever came forth.

Some tips for detecting and preventing course-cutting

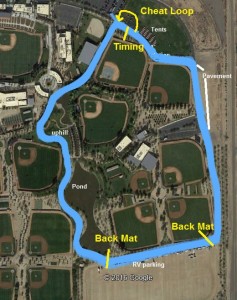

The first red flag for course-cutting is negative splits, especially in 100-mile races. Runners who can run the second half of a 100-miler faster than the first half are extremely rare. I analyzed four 2016 100-mile races and just a very small number of runners achieved a negative split and some of those might cause you to wonder. See: Negative 100-mile splits. At 2018 Rocky Raccoon, Patrick Wills, who was DQed, ran a negative split by 48 minutes, which is very significant and highly unusual. Loop races should have back mats with the ability to quickly check and flag patterns of misses. Timing areas should be clear and be placed away from runner aid stations and tents (and port-a-potties). Timers should watch runners who exit the course right after clocking a lap and they should not be allowed to head in the opposite direction after going through the timing area for any reason.

Most runners are totally honest

In contract, let me point out that the vast majority of runners in the sport run totally honest. I recall one year at Across the Years a runner reached 100 miles, acheiving his goal. He stopped even though he had more time to run and went home. But later from home he reviewed his lap times online and noticed that he was credited with a lap of just a few seconds, a timing problem because he was near the timing mat too long and it recorded him twice. He knew he had ran one half-kilometer lap short of 100 miles. He informed the race director and mailed back his 100-mile buckle. In another case a very prominent runner was returning home from a successful race. As he was thinking about his his race, he realized that by mistake he missed a section of the course. He turned around went back to the race and asked the race director to disqualify him. Mistakes do happen.

Safeguard our races

I’ll finish with the 1985 sad words of Gary Cantrell, “We cannot afford the luxury of entrusting our sport to the integrity of the participants. At least one legitimate ultramarathoner has been caught course cutting. How many (or few) have not been caught remains a matter of conjecture. . . . However painful the implicit distrust, we must safeguard our races against the dishonest competitor, or risk losing the fun that makes the races worthwhile.”

Just a quick note:

In the case of Parvenah Moayedi, Ultrasignup apparently wiped out the profile. She was DQ’ed from Rocky Raccoon 100 in 2013 (I think, can’t find confirmation anymore) a couple years after the fact, and should have been DQ’ed from Badwater 2014 but the RD never followed through.

https://ultrasignup.com/results_participant.aspx?fname=Parvaneh&lname=Moayedi

Those results can be viewed here: http://statistik.d-u-v.org/getresultperson.php?runner=164800

Thanks for that link. She was DQ’ed from Rocky Raccoon 2013. http://www.tejastrails.com/results-rocky-raccoon-2013

Excellent article! While it is sad, cheaters really end up hurting their family, friends, and fans.

RDs can take measures and I have decided offer services to starting mid 2018 to any RD who may want to have counter-cheating strategies in place.

Excellent article–well researched and written. It blows me away that anyone would cheat in a sport such as running. I’m glad to see that runners and race directors are starting to take this decades-long issue seriously and address the cheaters head-on.