December 3, 2004

Introduction

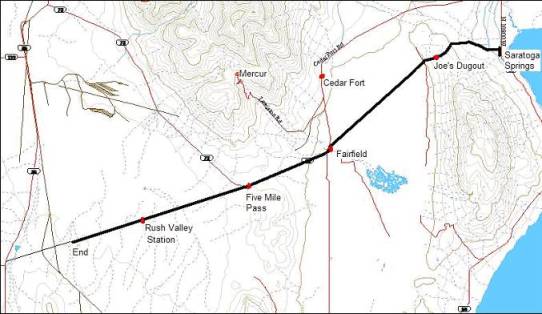

This is the story of an attempt to combine two of my passions: American history and ultrarunning. My history passion centers on the period of American History from 1840 to 1861, specifically involving the Mormon Pioneers. My running passion drives me to cover long distances in remote areas. (Participants in the sport of ultrarunning cover distances that exceed the traditional marathon length of 26.2 miles.) Bringing these two passions together seemed possible by running the historic Pony Express Trail that travels within three miles of my home in Saratoga Springs, Utah. I was determined to run a 145-mile stretch of the trail starting near my home, ending at the Utah/Nevada state border. In order to make the trip more interesting, I first went to work researching the history behind this portion of the trail. Little did I know the amazing events that once occurred out my back door in the west desert of Utah.

Day One (December 3, 2004): Saratoga Springs, Utah to Rush Valley – 31 miles

My run begins in the late morning hours of a frigid sunny day. I desire to brave the winter weather in an attempt to connect better with harsh circumstances that Pony Express riders had to face constantly. I dress in layers appropriate for the 21-degree temperature and use hand and foot warmers that will work great during the long run. I can’t help but think about how Pony Express riders had to accomplish their endurance rides without the benefit of high-tech clothing or gear.

Running across the farm toward Pony Express Trail

The first leg of my run would warm me up, a four-mile route across an expansive farm to connect with the Pony Express Trail. My wife Linda bids me goodbye as I start my run from my house and she is surprised how at how quickly I disappear. Soon she sees me a mile away, a small figure running across the wide-open farmland. The trail across miles of open field is at times covered with an inch or two of snow. I stop to put on YakTraks (like snow chains for the feet) giving me a little better traction across the drifts. Ahead on my route, I spy nine huge birds strutting together across the road onto the plowed field. As I run closer, I can see that they are large geese. My approach startles the gaggle and I pause to watch the beauty of these nine geese take off in formation, circle to the west as if pointing to me the direction to the Pony Express Trail.

Pony Express Elementary School

After cutting across a massive plowed field with uneven footing, my muscles feel warmed up and I feel great. I soon arrive at a new massive development named “The Ranches” located in a valley above Utah Lake. I run for a time on sidewalks, passing by the appropriately named Pony Express Elementary School. As I reach the location of the historic trail, a bell rings out in the air from the school, calling the children in from the cold playground.

When I talk to my friends about my long adventure runs or ultra marathon races, I get astonished reactions and many questions. I’m frequently asked, “how can you run so far?” This always leads to the question truly difficult to answer: “Why do you do it?” I’m sure the Pony Express riders had similar conversations about their long endurance rides. One rider wrote, “At first the ride seemed long and tiresome but after becoming accustomed to that kind of riding it seemed only play.” The same is so very true about ultrarunning. As your fitness level improves with training, the long runs indeed seem like “play.”

Pony Express riders were truly 19th century endurance athletes. Like ultrarunners, they kept track of their split times riding between stations, always trying to beat their personal records or even setting “course records” to their destinations. But the true victory for both Pony Express riders and for ultrarunners is to finish the race. One historian wrote that the story of the Pony Express was about “a lone rider facing the elements, racing time…involved in crossing the country, night and day, in all kinds of weather.” The same is true of the ultrarunner.[1]

The Pony Express story is about fast mail delivery. In our day we send mail around the world in seconds using the energy it takes to click a key with our finger. In the 19th century the time and effort to take mail across the continent was extraordinary. Instead of sending mail by ship, an overland coach mail service between California and the States began soon after the California gold rush. The overland route consisted of two distinct segments: California to Salt Lake City and Salt Lake City to Missouri. During the 1850s service was inadequate, irregular, and erratic. Harsh weather conditions, long distances, and Indian problems made it difficult to provide regular mail service.

In 1855 Howard Egan, one of the first pioneers to arrive in Utah with Brigham Young, outlined a direct route for overland mail along the fortieth parallel between Salt Lake City, Utah and Sacramento, California. By 1858, overland mail was traveling in coaches along this route. Later this became the Pony Express Trail on which I was running. Winter snows were a problem on the route, but when snow blocked the horse coaches, the mail was transferred to horseback or taken by men on snowshoes — perhaps the first extreme runners along the trail.

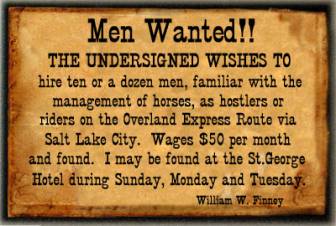

In 1860, the Pony Express company was established to greatly speed up cross-country mail delivery. Mail sent by ship took several months. Mail sent by overland coaches took at least one month. The Pony Express promised cross-country delivery in only ten days. Howard Egan was hired to build and equip the stations in western Utah and into Nevada along the Egan Trail. The system was a relay race. Riders would change about every one hundred miles. The riders would change horses every ten to fifteen miles. Daring riders were hired, “young, good horsemen, accustomed to outdoor life, able to endure severe hardship and fatigue, and fearless.” Ultrarunners can certainly relate to these last few characteristics. Mormons comprised the majority of riders and station keepers west of Salt Lake City.

Pony Express Parkway

After 50 minutes of warm-up running, I arrive at the historic Pony Express Trail. My pace picks up as I run on walking paths lining the Pony Express Parkway. I am impressed that the city of Eagle Mountain and their developers had the wisdom to honor the history of their community with road names in the area such as Saddleback Drive and Porters Crossing. I marvel to think that just four years ago this valley was mostly open and empty range, dotted with cedars. Now it was a small city of hundreds of homes, a victim of massive suburban sprawl. As I run in the bitter cold through these foothills dividing Utah Valley and Cedar Valley, I think of a cold Pony Express rider, Billy Fisher, who became lost in these same hills.

During the winter of 1861 Billy Fisher was lost for twenty hours in a blinding blizzard. He wandered off the trail on this divide among the cedar trees. “I didn’t know where I was, so I just got off my horse and sat down to rest by a thick tree which partly sheltered me from the driving snow. As I sat there holding the reins I began to get drowsy. The snow bank looked like a feather bed, I guess, and I was just about to topple over on it when something jumped on to my legs and scared me. I looked up in time to see a jack rabbit hopping away through the snow. I realized then what was happening to me. If that rabbit hadn’t brought me back to my senses I should have frozen right there. I jumped up and began to beat the blood back into my numbed arms and legs. Then I got back on my horse and turned the matter over to him. He wound his way [through] the cedars and after about an hour I found myself on the banks of the Jordan River [in present-day Saratoga Springs]. I knew now where I was so I followed the stream until I came to the bridge that led across to the town of Lehi. When I got there I was nearly frozen to death, but the good woman at the farm house I struck first, filled me with hot coffee and something to eat and I soon felt better. When I called for my horse she said, ‘You can’t get through this storm, better wait till it clears.’ ‘The mail’s got to get through,’ I said, and jumped on the pony and struck out.”[2]

The Pony Express’ first ride began on April 3, 1860 with both an eastern ride originating in Sacramento, California and a western ride originating in St. Joseph, Missouri. On April 7, 1860, the first pony rider from the west, Howard Egan, rode up this same trail I was running on. The first rider from the east, rode across this path two days later on April 9. Howard Ransom Egan wrote of his father’s famous ride along this stretch:

“It was a stormy afternoon…. The pony on this run was a very swift, fiery and fractious animal. The night was so dark that it was impossible to see the road, and there was a strong wind blowing from the north, carrying a sleet that cut his face while trying to look ahead. But as long as he could hear the pony’s feet pounding the road, he sent him ahead with full speed.”[3]

Site of Joe’s Dugout

As I continue my run westward on the Pony Express Parkway, I can hear the soft pounding of my feet on the road, which I’m sure was in stark contrast to the galloping pounding of Howard Egan’s horse’s hoofs on this same road 144 years earlier. I soon reach the historic site of the third Pony Express station from Salt Lake City — Joe’s Dugout. The site is unmarked and forgotten, being overwhelmed by development. It is located just west of a collecting area for runoff water. The land still consists of a small plowed field but seemly likely to be overgrown by development in the near future. I’m surprised the city that includes the pony express in their logo has done nothing to honor the only station in their borders.

In 1858 Joseph Dorton had visions of building a stagecoach station on this divide between Utah Valley and Cedar Valley. He built a rock house for his family, a barn, and a dugout to be used by travelers. The dugout was 20 feet by 30 feet, part of which was in the ground. Joe lived there during the days of the Pony Express, when it became a station.

My run becomes more labored as the trail climbs toward the top of the divide between the two valleys. The ten-pound pack on my back starts to feel heavy. It contains two liters of sports drink, a liter thermos of hot soup, some snacks, a warm jacket, and other usual running items such as duct tape and Band-Aids.

I am finally free of modern development as I cross over the pass and enjoy a fast long downhill run into Cedar Valley, a large expansive valley floor six miles across and twenty miles long. Cars still pass me with speed on the road. I’m sure the passengers are surprised to see a guy running on the soft shoulder of this road that normally never has pedestrians.

Running across Cedar Valley

At the valley floor, the trail leaves the parkway and became an isolated dirt road that runs diagonally southwest across the valley. I’m thrilled to leave the parkway (that heads to Eagle Mountain town center) and embark on the snow-packed road with no cars to dodge. I can see for miles in all directions across dry farms and open range. When Howard Egan chose the route for the trail in the 1850s, he understood very well that the fastest route between two points was a straight line. It isn’t much of a surprise that the Pony Express Trail was as straight as an arrow.

At Pony Express Memorial Regional Park

After a total of two hours of running, I reach the Pony Express Memorial Regional Park, about nine miles into the run. As I continue on through the wide and open valley toward the sun, I can see the town of Cedar Fort a few miles the west, nestled at the foot of the majestic Oquirrh mountains, with 10,422-foot snow-capped Lewiston Peak shining brightly in the sun. To the southeast I can see 11,928-foot Mount Nebo, 36 miles away, the highest point on the Wasatch Front.

Cedar Valley was first settled by Mormons in 1852, when Alfred Bell and others established a settlement in the north end of the valley, named Cedar Fort. By 1853 there were 150 people living in the small town. Five miles south of Cedar Fort is the small town of Fairfield that was established in 1855 near a spring at the foot of the mountains.

The sun warms me as I plod along the road heading toward Fairfield, which I can see in the distance as a grove of high trees. The long, level trail starts taking its toll on me and I start to intersperse some walking stretches between running spells. As I arrive at the small town of Fairfield, I tried to envision a camp of 2,500 United State soldiers stationed there in 1858, establishing Camp Floyd.

In 1857, distorted reports were received in Washington D.C. that the Mormons in the Utah Territory were in rebellion. President Buchanan sent out one third of the entire U.S. army to deal with the situation forcefully. This became known as “The Utah War.” To discourage the advancing troops, Mormons, who had the advantage of knowing the mountains and frontier conditions, harassed the troops as they approached the valley, scattering animals and destroying supply wagons. Brigham Young evacuated Salt Lake City and threatened to burn it down if the army entered it. Eventually a peaceful arrangement was reached and the army decided to camp at Fairfield.

The army brought about 6,000 head of horses, mules, and cattle, and 600 wagons filled with provisions and army implements. The soldiers spent their time in drilling, practicing. By 1860 Fairfield was a busy city of thousands, the third largest city in Utah with 7,000 inhabitants (3,000 soldiers, 4,000 civilians).

Sketch of Camp Floyd – March 3, 1860

In the evening, the civilian part of the camp sprang to life. “Kerosene lamps lighted the dance halls and gambling tables. Fiddles played and boot heels stamped out the rhythm of the dance…. Bullwhackers and mule-skinners, just in from the long freight roads, forgot their cares and abandoned themselves to the distractions of the camp. Stage drivers and pony riders mingled with the crowd, killing time between runs on the overland road. Pistol smoke, knives, horse stealing, etc., were too common to attract much notice.”[4]

Pony Express Display

At the three-hour running mark, I arrive at Camp Floyd Stagecoach Inn State Park. I stop for about 45 minutes, for lunch and to explore the historic park. I am pleased to see a nice display about the Pony Express Trail, inviting travelers to drive the trail ahead. Camp Floyd was the location of a Pony Express station and a monument describes its exact location. I eat a “wonderful” lunch of warm chicken noodle soup, a bottle of Ensure, some chips, and cookies.

Historic Trees

I refill my camelback bladder in the restroom and on the way back notice a huge tree. A sign on the tree indicates that John Carson, the founder of Fairfield, planted the massive Black Willow tree in 1858. He had ordered seedlings from San Francisco. I ponder that this tree was only a few feet high when the Pony Express rode by in 1860.

Stagecoach Inn

Nearby I see the Stagecoach Inn, a hotel built by John Carson in 1858. It was restored in 1959. A museum is across the street, which was the original commissary building for Camp Floyd. I wish that I had time to stop for a tour, but I would have to save that for another time. It was time to continue my run to the west on the Pony Express Trail.

“On April 7, 1860 there was more excitement in Camp Floyd. People were gathered on the walls of the fort and other buildings looking southwest toward the Five Mile Pass. Presently a shout went up, for in the distance was seen a dark object, which rapidly grew and took shape. It was a horseman riding on the run. On his saddle were two leather pouches—the first mail from California by the Pony Express!”[5]

The army remained there until July 1861 when the civil war broke out. “As suddenly as the camp had sprung into life it vanished. Wagons were loaded with necessary provisions, and the great stores that were left on hand were sold to the highest bidder.” The large city shrank to a tiny town of eighteen families.

One more landmark remains as a reminder of the military post, the cemetery, where lies about 56 bodies of the soldiers and civilian employees who died during the three-year occupation. The graves are unmarked, but a monument reads: “IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS, SOLDIERS AND CIVILIAN EMPLOYEES OF THE ARMY IN UTAH WHO DIED WHILE STATIONED AT CAMP FLOYD DURING THE UTAH CAMPAIGN FROM 1858 TO 1861 WHOSE REMAINS ARE INTERRED IN THIS CEMETERY. Erected by the War Department.”

I reflect how challenging it was for the few Mormon pioneer settlers in Cedar Valley to live so close to the Army Camp. Looking ahead to the west, toward File Mile Pass, the entrance to Rush Valley, as I run I reflect on a tragic event in 1859 that demonstrated the tension between the army and the Mormon settlers located in these two valleys.

Howard Spencer owned a ranch ahead in Rush Valley. One night a company of soldiers came and demanded to stay in his ranch house overnight and ordered Spencer to leave. A fight ensued with Spencer wielding a pitchfork. The officer struck Spencer with his gun barrel, fracturing Spencer’s skull. A few months later the officer was indicted by the grand jury for assault with the intent to kill. When he came to Salt Lake City for trial, Spencer shot him and the soldier died four days later. The tragic news arrived at Camp Floyd enraging the soldiers. About twenty soldiers marched that night to the town of Cedar Fort and set fire to hay stacks, sheds and corrals. Shots were exchanged and the soldiers “shot up the town” indiscriminately, but no one else was hurt. Such was the unfortunate conflict between the soldiers and the Mormon settlers. One officer told a visitor to the fort, “They hate us, and we hate them”[6]

The Pony Express route now took me along a well-traveled highway for the next five miles to the top of File Mile Pass. The incline is moderate, but it feels difficult as my full stomach tries to deal with my lunch. I recognize that I am running through the heart of what used to be Camp Floyd and wonder if people have excavated the area with metal detectors. To the north, three miles away, I look up Manning Canyon, climbing into the Oquirrh mountains. I think of a large town that once flourished up that canyon.

Gold was discovered at the head of Manning Canyon in 1870. A few men struck it rich in only a few months. Gold fever pulled at people to swarm up the canyon and the town of Lewiston (later renamed Mercur) was established. At its height, there were 5,000 people living up in the canyon. But as fast as the city grew into existence, it disappeared just as fast as the gold dried up, becoming a ghost town. As gold and mercury were discovered again, the town had a rebirth. In 1896 a fire nearly destroyed the entire town. Mercur was soon rebuilt and was again destroyed by fire in 1902. That boom lasted until 1913 when deposits failed. By 1925, Mercur was once again a ghost town. Today there is nothing left of the town that has been destroyed by modern strip mining. Newer processes made it profitable to go through the old tailings and recover even more metal. The town site is off limits as efforts are being made to “reclaim” the land and replant with natural vegetation.

As I run up the highway shoulder, cars and trucks speed by at a rate of 65+ m.p.h. Most are courteous and give me a wide berth, but some, especially the semis, cruise past me as if I wasn’t there. I consider the dangers during my run compared to the dangers that the Pony Express riders faced. The greatest dangers I face are being sideswiped by cars or running up against drunk kids shooting out in the desert. The Pony Express riders faced constant dangers from Indian attacks. Many lost their lives. I look to the south and see the Tintic mountain range.

Chief Tintic, a renegade Goshute Indian, roamed these hills with his tribe. In 1856 the “Tintic war” occurred in this valley. The Indians had been accused of stealing cattle from nearby herds. A posse of men from Provo with warrants set out to arrest Chief Tintic and his band. Tintic was camped near Fairfield. After dark, in Cedar Valley a battle occurred. One member of the posse was killed along with an Indian woman. Several other Indians were wounded. During the night, the Indians moved their camp over Five Mile Pass into Rush Valley. Those at the rock fort located at Fairfield could hear sounds of moaning and crying from the Indians. During the night, some Indians rode to Utah Lake and inflicted revenge by killing two men who were herding cattle (near my home in present-day Saratoga Springs.) When daybreak came, the posse from Provo rode over Five Mile Pass into Rush Valley and found the Indians entrenched on a hill among some protective rocks. Shots were fired and the Indians said they were hungry for a fight. The posse decided to retreat. When they returned later, the Indians were gone.[7]

My run continues. At the four-hour mark I reach the Five Mile Pass Recreation area, BLM land that on weekends is covered with ATVs and dirt bikes.

A few famous people passed through this remote section during the 19th century. Mormon pioneer, Parley P. Pratt was perhaps the first non-Indian to go over this pass, in 1847. Brigham Young was here on an excursion in 1854. Others to ride this section included Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, Schuyler Colfax, Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1865, and Sir Richard Burton in 1860.

After Five Mile Pass, the trail leaves the highway and turns straight west, heading into Rush Valley, wide-open landscape left much as it was in 1860. I am pleased to be away from the highway and the noise of civilization. All becomes quiet as I run toward the setting sun. An ATV trail parallels the road. My spirits rise as I run on the soft dirt trail filled with drifted snow. I’m astonished to see thousands of jackrabbit tracks in the snow, in every direction. In 1860, Richard Egan, a pony express rider started a westward ride along my route from Camp Floyd (Fairfield) to my next station destination, East Rush Valley.

Egan’s ride was during a blinding snowstorm. “As night approached, the snow was already knee-deep to his horse. Soon it was so dark and snowy he could not see the trail. In order to stay moving in the general direction, Egan kept the wind at his right cheek as he traveled all night. At dawn, after an exhausting ride, he found himself back at his starting point [Camp Floyd]. The wind had changed direction during the night, and he had ridden 150 miles in a vast circle. Undaunted, he immediately mounted a fresh horse and continued on to Rush Valley Station without a rest stop.”[8]

After a couple miles, I stop to look around me. As far as my eye could see, there was nothing man-made to be seen except for the paved road. There was not a structure in sight to all the horizons. The remote feeling is both invigorating and a little fearful. Here I am out in the middle of nowhere, with frigid temperatures, left to my own skills and fitness to stay warm and out of danger. I watch the sun disappear behind the Onaqui Mountains ahead. Immediately the warmth disappears and then the temperature drops into the teens. I pick up the pace in order to keep warm.

Monument at East Rush Valley Station site

At the six-hour mark into my run I reach the East Rush Valley Pony Express Station site. An impressive stone monument marks the location. It has been sadly vandalized by thoughtless shooters. The plaque is missing and only a portion of a picture of a horse gives the visitor a clue as to why the monument is there. The Daughters of the Utah Pioneers put the monument there in 1965. I pull out my headlamp and call Linda to start the long drive to pick me up.

Normally, as I approach the 30-mile mark into runs, I gain my second wind and feel unstoppable. The same is true at this point. I feel great, but the chill of 16 degrees is finding its way into my bones. I continue my run toward an impressive crimson sunset. A few vehicles pass me along the way. They all slow down, surely in shock to see a guy running in the dark, out in the middle of nowhere. I wave so they know I’m fine. The stars pop out into the night sky and I can see lights of civilization shining from the Toelle Army Depot, eight miles to the north.

After several miles, Linda and my eight-year-old son Connor pull up in our van. My link back to civilization and the 21st century has arrived. I feel so fine that I ask if I could run for a couple more miles, with Linda driving behind. I shed my pack, put on a warm jacket, and run fast and wild up the road. After awhile, Linda pulls forward, stops, and out jumps my son Connor who wants to run with his dad on the Pony Express Trail. Explaining the history about the trail is difficult to be understood by the mind of a modern eight-year-old. No cars? No telephones? No trains? Indians!!! That perks him up and he is astonished to learn that Indians lived where we were running.

Returning to the site of the chase

An oncoming truck slows and passes by us. The guy in the truck just cannot figure out what is happening. For many minutes he turns around, comes forward, pulls back, and finally drives up beside us. “Are you OK?” he asks. I laugh and tell him all is well. He says, “Oh, I thought you were been chased.” I explain that we are only out for a run. That was very thoughtful of him to worry. I laugh at the thoughts that probably were going through his mind. Why in the world would a guy and his little boy be running ahead of a car, in the middle of the desert, at night, in the frigid cold? Surely he left thinking we were insane. Ultrarunners are used to such reactions.

Finally I decide to pack it in for the night. I reach the seven-hour mark, 31 miles, or 50K. I mark the location on my GPS and plan to continue from this point on another day.

[1] Christopher Corbett, Ophans Preferred, p 9.

[2] Kate Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 3, p.379-80

[3] Kate Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 3, p.368

[4] Kate Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 1, p.99

[5] Kate Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 2, p.26

[6] B. H. Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 4:505, and Sir Richard Burton, City of the Saints

[7] LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, Andrew Jenson, Vol. 1, p.498, Our Pioneer Heritage, Vol. 9, p.398.

[8] Joseph J. Di Certo, The Saga of the Pony Express, p. 180